As a final goodbye from the Trainees of the year 22-23 we thought we’d share with you a look at some of the trainee projects which were presented at the showcase this year! These descriptions, each written by another trainee who viewed the original presentation, are designed to give you a flavour of what our year with the Bodleian and College libraries have been like.

Jenna Ilett: Creating an interactive map of the Nizami Ganjavi Library

By Alice S

Kicking off our Trainee showcase with a bang, Jenna’s presentation hit all the right buttons. With an amusing title and appropriately themed presentation, Jenna talked us through the ins and outs of coding an interactive map, complete with hoverable shelfmark labels!

The inspiration for this project came from a slew of wayfinding projects that have been taking place across the ‘Section 3’ Libraries (which include the Taylor, The Art Archelogy and Ancient World and the Nizami Ganjavi libraries) as well as Jenna’s own background in tech thanks to a GCSE in Computer Science and a module in Web Design during her undergraduate degree.

Using Inkscape, Jenna made the underlying vector graphic for the map itself, working off a previous design, but keeping the styling consistent with maps currently available at the AAAW Library. She used the feedback she received to refine her design before moving on to the coding itself.

The coding was done on a code editor called CodePen which allowed her to keep track of the HTML, CSS and JavaScript code all in one view. Jenna whizzed us through an impressive array of coding tips including running through how she used tooltips to enable the hoverable shelfmarks to display over the appropriate shelves.

Remaining humble throughout, Jenna also treated us to an inside look at her thought processes in the form of increasingly anxious WhatsApp messages she had sent about her project to friends and colleagues, as well as a demonstration of a particular bug that caused her map to flip itself over when zoomed out, both of which earned a hearty chuckle from the audience. But with the amount of skilled work Jenna has put in already, the audience and I are in no doubt that Jenna will soon have the kinks worked out, and the Nizami Ganjavi Library will have a swanky new interactive map!

The most interesting thing I learnt from Jenna’s presentation would probably have to be the benefits of scalable vector graphics. As someone who has all too often fallen foul of the perils of trying to resize images only to be left with a grainy and illegible mess, it’s great to know that using a vector graphic will allow me to scale an image to any size my heart could desire. Through the magic of mathematical graphing it preserves the shape and position of a line so that it can be viewed at any scale. Thanks to Jenna for a fabulous presentation and enlightening me to the wonders of vector graphics!

Alice Zamboni: Audio-visual archive of former Prime Minister Edward Heath

By Charlie

The second presentation of the day came from Alice Zamboni, one of the two Digital Archivist trainees based for two years with the Special Collections team at the Weston Library. Alice’s project was concerned with adding the audio-visual material donated by former Conservative Prime Minister Edward (Ted) Heath to our catalogue.

As with most of his predecessors and successors in the role of Prime Minister since the Second World War, Ted Heath began his political involvement at Oxford, studying PPE at Balliol College and winning the Presidency of the Oxford Union in 1937. Therefore, it is no surprise that the Bodleian chose to purchase his personal archive in 2011 to add to its collection. Covering mainly the period from the mid-1970s to the early 2000s, Alice related how many of the cassettes and tape reels held information on music and yacht racing connected to the love of European culture which inspired Heath’s drive – and eventual success – to gain admission for the UK in the European Community in 1973.

Most of the material was held in analogue formats so Alice’s first step before cataloguing was to convert them into digital MP3 files. Then, one of the main challenges she faced was that the sheer scale of the material (481 tapes some up to ninety minutes long) meant that not every recording could be listened to in its entirety. An educated assessment on the contents, and how it should be catalogued, had to be made from listening to a portion of each. This allowed some of the material, such as recordings made from radio programmes, to be weeded out of the collection.

Perhaps the most interested thing I learned from Alice’s talk was the broad scope of Heath’s recordings, including some in foreign languages. One interestingly was in Mandarin Chinese, and of a children’s programme on learning languages.

As with most of the trainee projects, there is always more to be done after the showcase and Alice’s next main step is to place the original tapes back into boxes according to how she has catalogued them. An even longer-term plan for ensuring that the archive can be opened to researchers is acquiring the rights for many tapes recorded from musical recitals, for instance, where the copyright is owned by the composer or conductor rather than Heath himself.

Miranda Scarlata: Web archiving and the invasion of Ukraine.

By Jenna

Although the phrase ‘once it’s on the internet, it’s there forever,’ is common, Miranda’s talk highlighted the ephemeral and volatile nature of websites, and the importance of capturing and preserving information from these sites.

Although it would be impossible to capture every single website in existence, there are times when the digital archivists undertake a rapid response project – for example capturing information on Covid-19, or the ongoing war in Ukraine – the latter being the focus of Miranda’s talk.

Soon after the Russian invasion of Ukraine (on the 24th of January 2022), the Digital Archivist team launched a rapid response project to preserve information regarding Ukrainian life and culture, as well as the war itself, which was at risk of being lost. A campaign was launched that asked people to nominate websites that fit certain criteria.

Miranda discussed some of the challenges involved in a project like this. Although 53 sites were nominated, only 21 were deemed viable. Twitter accounts of Ukrainian citizens were also included, and additional news, cultural and war specific sites were crawled, leading to a total of 72 sites. There is a limit on how many sites can be preserved due to the strict data budget, which means that difficult decisions had to be made about what to prioritise. Another added level of complexity was the limited Ukrainian and Russian language skills within the department, which made it difficult to determine types of content and assign metadata tags.

The normal processes when archiving websites involves contacting site owners to obtain permission before beginning the capturing process, but due to the high risk of information loss, site owners were contacted after capturing the sites to gain permission for publication. With the help of a Ukrainian and Russian speaking intern, site owners were contacted, but there was an understandable lack of response given that many of the site owners would have been directly impacted by the war.

Miranda’s talk was a fascinating insight into the world of digital archiving and the challenges within, particularly with the more arduous and intricate rapid response projects, which are hugely important when it comes to capturing important events as they are happening.

The most interesting thing I learnt was that digital archiving involves capturing a functional version of the site that could continue to exist even if the original host site was removed, rather than a static capture, which leads to added complexity when it comes to external links and embedded content.

If you are interested in this project and want to nominate a website for archiving please fil in the nomination form here: BEAM | Nominate for archiving (ox.ac.uk)

Caitlín Kane: Maleficia: Curating a public exhibition at New College Library

By Alice Z

In her talk on the exhibition that she undertook as her trainee project, Caitlín focused on her experience of organising and curating the exhibition of rare books and manuscripts from the collection at New College. A chance encounter with the New College copy of Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches), a well-known 15th century treatise about witchcraft, sparked in Caitlin the idea of organising a display of special collections about magic, witchcraft, and astrology.

The promotional material devised by Caitlín to advertise the exhibition on social media and in print was what stood out most for its originality and it is clearly something that contributed to making the exhibition a success in terms of visitor numbers. I think the most interesting thing I learned from her talk was how you can create moving graphics using services such as Canva and how these can be used on social media to promote events such as exhibitions.

Caitlín reflected on some of the logistical challenges of organising this kind of collection-focused public engagement event, such as the selection of material and collection interpretation. For one thing, identifying relevant material from New College’s collection of manuscripts was more difficult in the absence of an online catalogue. Without the benefits of a neatly catalogued SOLO record to guide her, she was required to rely on previous staff members’ handlists as well as serendipitous browsing of New College’s rare books shelves.

Another aspect of the exhibition she touched upon was the interpretation of the materials. It was important for the labels accompanying the items on display to strike the right balance between content and context. Providing insights into the objects themselves was key, especially as many were texts written in Latin, but so was giving visitors enough background on the early modern philosophical and theological debates underpinning witchcraft.

Caitlin’s work clearly resulted in a fascinating and well-attended exhibition, and she was able to make great advances in increasing awareness of some of the amazing collections held by her library.

Abby Evans: Professor Napier and the English Faculty Library

By Miranda

Abby’s trainee project concerned a fascinating collection of dissertations and offprints gathered by Professor Arthur Napier, a philologist and Professor at Merton College in 1885. Held by the English faculty library, this collection consists of 92 boxes

containing 1058 items that needed to be reassessed ahead of the library’s move to the new Schwarzman centre for the Humanities in 2025.

Her project showcased the speedy decisions and minute details that must be considered when working at a library as she had only two weeks to determine the content of the collection and assess what material was worthy of making the move to the new building. The process required lots of skimming through documents to understand their content, the deciphering of previous systems from librarians past, and a strong head for organisation!

The collection itself was also able to provide some insight into how the English Faculty used to operate. Many of the materials were annotated with small markings and references to an older organization involving different box numbers and labels.

The collection also surprisingly held works from female authors – a rarity for the time – but their work was clearly well-enough regarded that Professor Napier saw the benefit in collecting and preserving it in his collection.

The most interesting insight the Napier collection provided however is perhaps its demonstration of the of the workings of Royal Mail years gone by. The collection contained several items which bore evidence of travelling through the UK postal system, some which were simply folded up with the address written on the back – no envelope required! Additionally, a simple name and general neighbourhood were enough to get the letter to its intended location, postcodes clearly had yet to hit it off!

Overall, Abby’s talk demonstrated the myriad of small and large details that must be considered when continually maintaining library collections. And the efficiency with which she was able to work through the collection is an example to us all!

Morgan Ashby-Crane: Making Collections More Visible: Displays and Data Cleanup

By Caitlín

At the SSL, Morgan embarked on a mission to improve the visibility of collections, both in making items easier to locate within the library system, and in highlighting diverse voices in the collections.

During awareness months throughout the year they curated book displays which allowed them to improve the circulation and physical accessibility of collections such as those for Black and LGBTQ+ History. For Black History Month, they asked subject librarians to recommend a book with an accompanying caption. Morgan then curated the display, and added QR codes linked to e-resources that the subject librarians recommended. They then collated these into a post on the SSL blog to reach those who couldn’t access the display physically.

For LGBT+ History month, Morgan organised another pop-up display, but this time the focus was on recommendations from readers in previous years. One of the most interesting ideas I gleaned from Morgan’s presentation was their approach in designing new recommendation slips for readers to fill in and recommend their own books to make sure the displays stayed relevant to reader interests. As books were borrowed and recommendation slips filled in, Morgan was able to track the circulation of items and provide evidence of engagement.

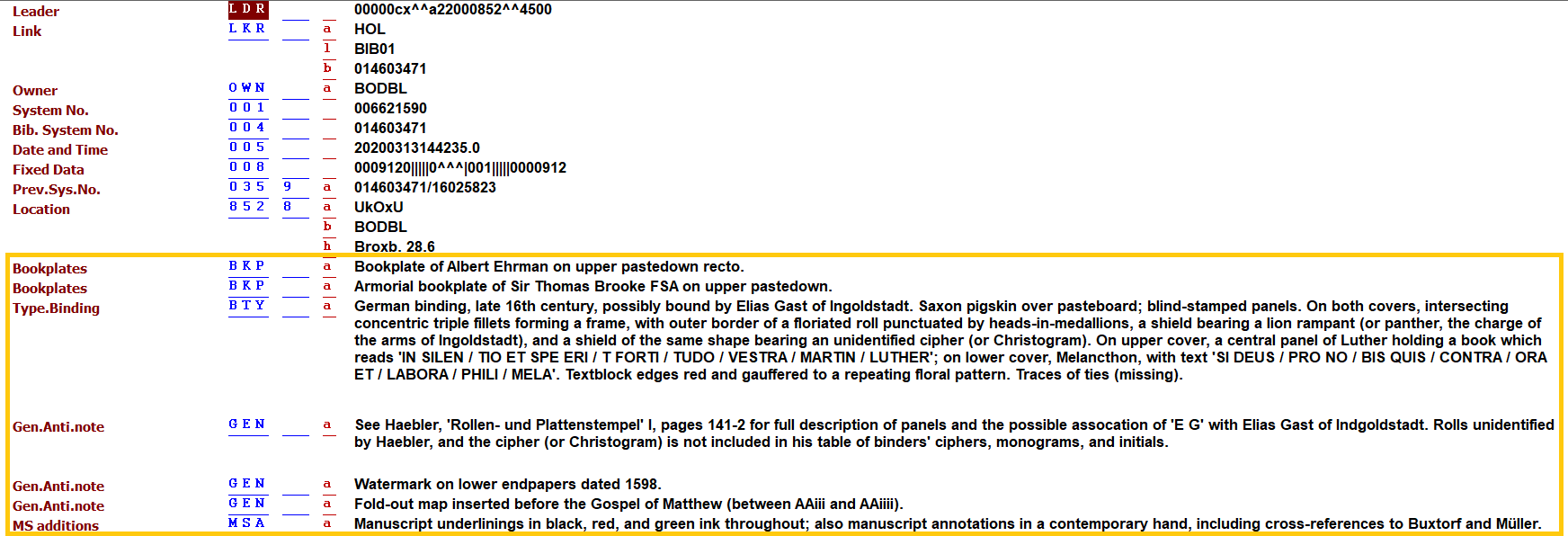

Another way in which Morgan improved accessibility to the collections was in cleaning up data on Aleph, our old library system. Over the past few months, the trainees have been busy helping our libraries prepare for the changeover to a new library system, Alma. With thousands of records being transferred across, a lot of data clean-up has been required to make sure records display correctly in the new system.

Some outdated process statuses, such as AM (Apply Staff – Music), can be left attached to records long after they fall out of use. Other books, that are on the shelves to be loaned, can be left marked as BD (At bindery). To single out any irregularities, Morgan made a collection code report to see if any items stood out as unusual. When items appeared under unusual process statuses, Morgan investigated them further to see if their statuses needed changing.

Similarly, some items without shelfmarks had slipped under the radar, and Morgan set about adding them back to the books’ holdings records. They worked backwards from potential Library of Congress classifications to figure out where the books might be on the shelves and, once they’d identified the physical shelfmark, restored it to the item’s holdings record. These data cleanup tasks will make it easier both for readers in locating the items they need and will help the collections transition smoothly from Aleph to Alma.

Ruth Holliday: Investigating the Christ Church Library Donors: Research and rabbit holes

By Abby

For her presentation, Ruth discussed her project to research donors to Christ Church’s ‘New Library’, with a particular focus on their links to slavery. The incongruously named New Library was constructed between 1717 and 1772, and over 300 benefactors contributed to the project! Given the time constraints involved, in this presentation Ruth chose to focus on just three:

The first donor Ruth spoke about was Noel Broxholme, a physician and an alumnus of Christ Church, who during his time there was one of the first recipients of the Radcliffe travelling fellowship. This was a grant established by Dr John Radcliffe (a rather omnipresent figure in Oxford) that required medical students to spend years studying medicine in a foreign country. Ruth was able to establish that at one time Doctor Broxholme was paid for his services not in cash, but instead in ‘Mississippi stock’. As one might be able to deduce from the name, this was effectively shares in companies who had strong ties to the slave trade.

The next donor Ruth discussed was George Smallridge, Bishop of Bristol. Again, we have a man whose profession is seemingly at odds with involvement in the trade of human lives. However, as part of his donation for the foundation of the new library he included two lottery tickets. One of the prize options for that lottery was South Sea Stock – more shares with ties to the slave trade. It has proven difficult to determine whether the tickets he donated were, in fact, winning tickets, or whether they were ever cashed in, but once again the foundation of this library has found itself fiscally linked to slavery.

The final donor to feature in Ruth’s presentation was Charles Doulgas, 3rd Duke of Queensbury, whose financial investments included shares in the British Linen Company. Whilst British linen does not ostensibly appear to have clear ties to slavery – being both grown and manufactured domestically by paid labour – there is in fact a significant connection. Whilst cotton was becoming the more popular fabric for textile production in the mid-late eighteenth century, the fabric was seen as too good to be used to clothe the people forced to grow it. As such, linen, in its cheapest and least comfortable format, was exported in droves to be used to clothe the slaves labouring on cotton plantations.

What all these donor case studies in Ruth’s fascinating presentation showed, and probably the most interesting thing I learned, was how enmeshed slavery was in the eighteenth-century economy. Whether in the form of shares received in lieu of payment, shares won as prizes, or as custom to the textile industry it was growing to dominate, Ruth’s project demonstrated that making money in the eighteenth century was almost inextricably tied to slavery.

Rose Zhang: As She Likes It: The Woman who Gatecrashed the Oxford Union

By Morgan

Rose’s project and subsequent presentation touched on a captivating aspect of the history of women at Oxford. As the trainee for the Oxford Union, she undertook some first-hand research on an unusual event in the early history of women’s involvement in the Union’s debates.

Rose first gave us a summary of the Union’s history. Set up in 1823 (and therefore currently celebrating their bicentenary), The Oxford Union has been famous (and infamous) for its dedication to free speech over the years. As women were only formally admitted to the University itself in 1920, it is unsurprising that they were also barred from entry to the Union debating society. This restriction against women members continued until well into the latter half of the 20th century, although rules had become laxer by this point, allowing women into the debating hall itself, but only in the upper galleries.

By the 1960s, there was increasing pressure from female students who wished to access the main floor of the debating hall, rather than be confined to the gallery, where they were expected to be silent, and could not get a good view of the proceedings. The pressure built to a point in 1961, when two students achieved national press coverage for their successful gate-crashing of the debating chamber, which they did in disguise as men!

Rose gave us a captivating account of the gatecrashing, using newspaper clippings from the time and information from one of the gatecrashes herself, Jenny Grove (now a published journalist), to really bring this moment of Oxford History to life. One of the most interesting things I learned from Rose’s presentation was how library projects can handle, preserve and communicate data that’s less discrete – which tied in well with our keynote talk from Phillip Roberts, especially focussed on how heritage organisations have a power to preserve and convey stories that otherwise might be suppressed or overlooked.

Thankfully, the actions of Jenny grove and her co-conspirator Rose Dugdale were successful in bringing wider attention to the issue, and within two years successive votes won women the right to be full and contributing union members.

Rose’s presentation on this project was interesting not just for such a fascinating bit of history, told with good humour, but also for how it differed to most trainee projects methodologically in using first-hand oral histories to bring context to her library and its collections.

Grace Exley: Creating online exhibitions

By Ruth

One of the later presentations in the day, Grace kept the energy flowing as she discussed her experience creating online exhibitions. The inspiration for Grace’s project was accessibility. While Jesus College puts on termly exhibitions in the Fellows’ Library, not everyone can make it on the day, and having some kind of record of past exhibitions would be beneficial to many.

Taking the initiative, Grace sought out training on how to curate and manage online exhibitions. She worked her way through a course which introduced her to the platform Omeka. Using Omeka, visitors can scroll through photos of the exhibition items and read captions for each one, making it both a great way to experience exhibitions that you cannot make it to physically, and a way of preserving physical exhibitions in a digital space.

With this new knowledge at her fingertips, Grace set out to organise her own exhibitions that she would subsequently upload to the Jesus College website using the Omeka platform. The books that featured in these exhibitions were selected by Grace from the Fellows’ Library at Jesus College – a stunning 17th century room that holds 11,500 early printed books.

Grace told us about the botany exhibition she curated in Michaelmas term, which featured a first-time find of an inscription in John Parkinson’s Theatrum Botanicum. One of the most interesting things I learned from Grace’s presentation is that this is one of the very few books in the Fellows’ Library to have had its title page inscribed by a female owner, Elizabeth Burghess. From the style of the handwriting, we can tell that the signature is likely to have been penned near to the time of publication, though we don’t know for sure who Elizabeth Burghess was.

We were in a Jesus College lecture theatre for the showcase, and due to running ahead of our schedule we were able to sneak into the Fellows’ Library and look around. It’s a gorgeous space, and it was great to see where the exhibitions take place when they’re in 3D! If you’re interested, you can view Grace’s Botanical Books exhibition along with some of Jesus College’s other exhibitions on the website the Grace created here: Collections from the Fellows’ Library and Archives, at Jesus College Oxford (omeka.net)

Alice Shepherd: The Making of a Disability History LibGuide

By Rose

A theme running through many of the trainee projects this year was accessibility, and Alice proved no exception. For her trainee project, she worked on creating a LibGuide on Disability History, to help people find resources relevant to researching that topic.

A LibGuide is an online collection of resources that aims to provide insights into a specific topic of interest. They are created across all Bodleian Libraries and often act as a launch pad for a particular subject to signpost readers to the plethora of resources available. The resources for Alice’s LibGuide were largely collated during a Hackathon event organised by the Bodleian Libraries team, during which 36 volunteers shared their expertise on Disability History and put together a list of over 231 relevant electronic resources on this topic.

Alice started by working through this long list of resources. She spent a considerable amount of time cleaning, screening, and processing the data collected at the Hackathon. Specifically, she removed website links that were no longer active, evaluated the quality of the materials, and carefully selected those that were most appropriate and relevant to the topic of Disability History.

With this newly complied ‘shortlist’ of scholarly resources, Alice then started putting them together on the LibGuide website, adapting the standardised Bodleian LibGuide template to better fit the needs of researchers by including resources grouped by date, topic, and format. With the resources carefully curated and added to the LibGuide, Alice put some finishing touches on the guide by doing her own research to fill in some of the gaps left after the Hackathon.

There will be a soft launch of the LibGuide in the Disability History month this year. Although this LibGuide is mainly created for students and scholars with research interests in Disability History, the LibGuide will be available to the public as a valuable educational resource.

Charlie Ough: Duke Humfrey’s Library Open Shelf Collections

By Grace

As the trainee for the Bodleian Old Library, Charlie gets the tremendous pleasure of working in the Medieval precursor to Oxford’s centralised Bodleian libraries, Duke Humfrey’s Library.

Whilst the setting and atmosphere may be one of academic serenity, after a few months of working there, Charlie identified that something ought to be done to make the organisation of its Open Shelves Collection slightly less chaotic. He had found that books were difficult to locate, some were physically difficult to access, the shelf marks were confusing, and certain volumes from the collection were missing entirely.

With a plan in mind, the first task in addressing this issue was to create a comprehensive list of everything on the shelves. Part way through this venture, Charlie stumbled across a file hidden away in an archived shared folder from 2017 and discovered that a previous trainee had already make a handlist for Duke Humfrey’s. This saved lots of time and allowed him to focus on making improvements to this cache of information by slimming it down, rearranging it according to area, and dividing it into different sections.

During this time Chalrie also designed and conducted a reader survey that was distributed within Duke Humfrey’s to determine who the main users of the library are, and whether they were there to use the Open shelf books specifically, or more because they enjoyed using the space. With the results of that survey to sort through and analyse, Charlie now has a permanent position working at the Bodleian Old Library and intends to continue working with the Duke Humfrey’s Open Shelves Collection. His plans involve new shelf marks, updating the LibGuide, a complete stock check, and barcoding the collection.

The most interesting (and mildly terrifying) thing I learned from Charlie’s talk is that the population of cellar and common house spiders in the Duke Humfrey’s Library ceiling were intentionally introduced at the beginning of this century, to combat an infestation of deathwatch beetle that was burrowing into the wooden beams and panels. In fact, the spiders still thrive there to this day! Not something to think about when you’re peacefully studying in the picturesque Duke Humfrey’s Reading Room…

![Vol. 01[1], t.4: Fraxinus Ornus](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/oxfordtrainees/wp-content/uploads/sites/133/2017/06/plasci002_aaf_0020_3.jpg)

Recent Comments