For LGBTQ+ History Month, a selection of the trainees (alongside the St Antony’s Apprentice Library Assistant) have come together to share how LGBTQ+ History is represented across the libraries. Between displays and notable books, libraries provide an important place to learn and reflect on the progress and successes the community has achieved.

Jess Ward and Josie Fairley Keast, Law Library

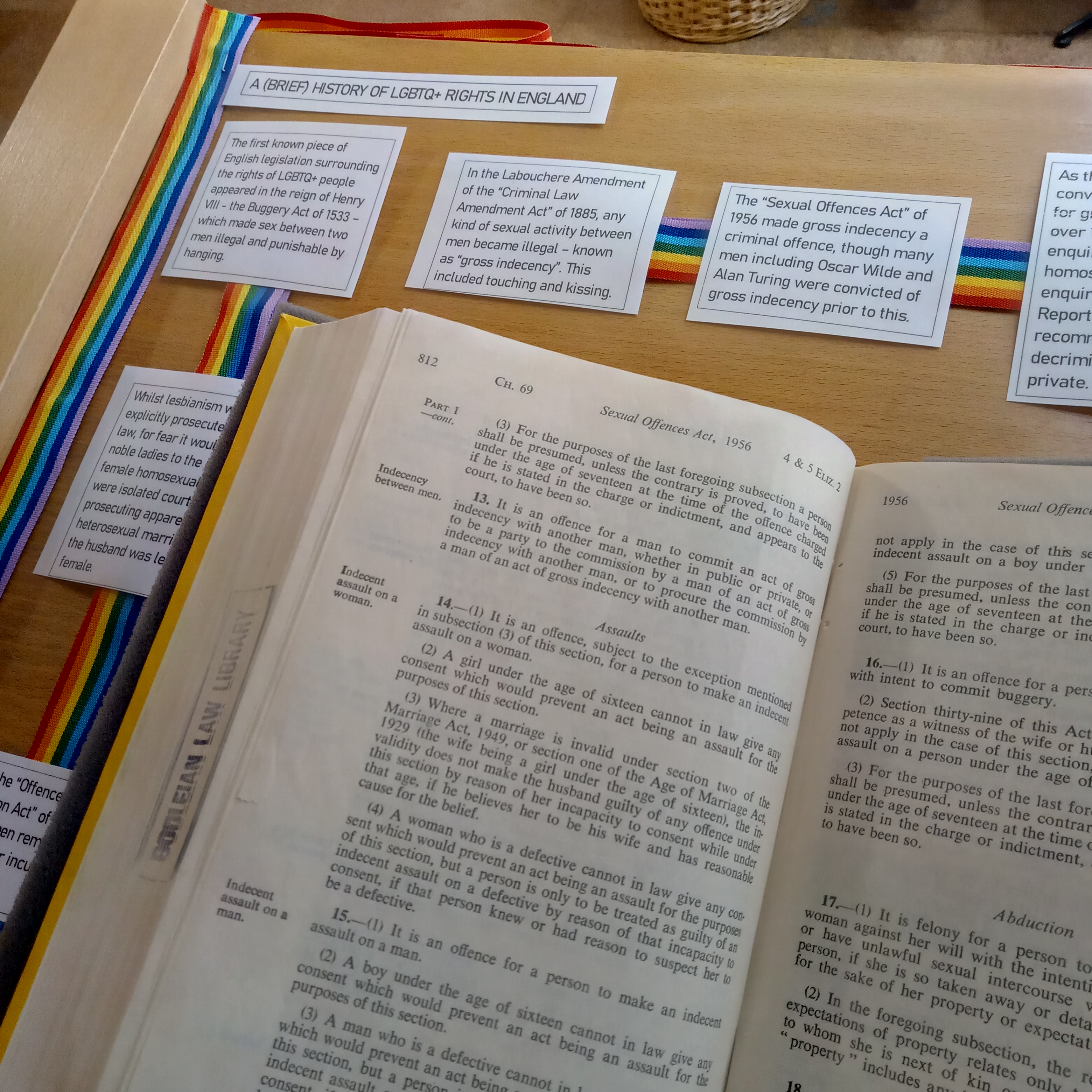

The Law Library’s LGBTQ+ History Month Display

For LGBTQ+ History Month, Jess has put together ‘A [Brief] History of LGBTQ+ Rights in England.’ On display from the library’s physical collection are the Sexual Offences Act 1956 and the 1967 Amendment, the Gender Recognition Act 2007, and the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013, with many other examples from the sixteenth century to the present day summarised and cited. The book display traces the progress that has been made since the first mentions of LGBTQ+ individuals in English law, but also highlights some of the issues still facing members of the community today.

Yoshino, Kenji. Covering : The Hidden Assault on Our Civil Rights. New York: Random House, 2006.

KM208.U4.YOS 2006

Outside of actual legislation, another recommendation is Kenji Yoshino’s 2006 memoir Covering: The Hidden Assault on Our Civil Rights. This book intertwines legal scholarship and social history with Yoshino’s lived experiences as a gay Asian-American man, reflecting on the state of civil rights and identity politics in mid-2000s America.

“I surfaced back into my life. I made decisions with persuasive efficiency. I chose the American passport over the Japanese one, the gay identity over the straight one, law school over English graduate school. The last two choices were connected. I decided on law school in part because I had accepted my gay identity. A gay poet is vulnerable in profession as well as person. I refused that level of exposure. Law school promised to arm me with a new language, a language I did not expect to be elegant or moving but that I expected to be more potent, more able to protect me. I have seen this bargain many times since – in myself and others – compensation for standing out along one dimension by assimilating along others.” (Covering, p. 12)

Izzie Salter, Sackler Library

Venegas, Luis. The C*ndy Book of Transversal Creativity : The Best of C*ndy Transversal Magazine, Allegedly. New York, 2020.

TR681.T68 C36 CAN 2020

‘On the pages of C*NDY Transversal, [Luis Venegas] acknowledged queerness in fashion, highlighted people all-but-forgotten in LGBTQ history, and introduced an audience to up-and-comers who were changing the landscape of music, runway, and trans culture – and he did it with a glamorous twist. C*NDY was beautiful.’ (p.44)

In 2009, Spanish independent publisher Luis Venegas launched the first issue of C*NDY Transversal Magazine. C*NDY set out to create ‘something like a trans vogue’, celebrating everything ‘transversal’. In Venegas’ own words, this encapsulates trans, gender non-conforming, non-binary and androgynous people, as well as ‘male and female impersonators and drag queens’ – all whom he believes ‘basically break the outdated rules of gender’. Since the first publication, C*NDY has developed a cult following and grown in traction. Later issues have featured renowned LGBTQ+ celebrities such as Miley Cyrus, Laverne Cox, Janet Mock, and Lady Gaga. However, each issue goes beyond the celebrity: they are filled with portraits of trans rights activists, drag stars, androgynous models, LGBTQ+ embraces.

The Very Best of C*NDY Transversal Magazine, Allegedly is a collection of some of C*NDY’s most iconic spreads. Highlights include model Connie Fleming posing as Michelle Obama, headshots inspired by Candy Darling, and a letter to Venegas from a young transgender fan (p. 251). The latter is particularly significant, a reminder of the importance of celebrating LGBTQ+ people and expression in the past and present.

Readers can enjoy these highlights on glossy pages – akin to the magazine itself – and also read quotes from those who are featured. Many of these offer real insight into the importance of C*NDY, with contributors sharing their appreciation for the visibility it provided. Meanwhile, many quotes are punchy quips about gender expression and identity. These combine to make a book of boldness, of beauty, and aspiration.

Venegas has made it clear that – whilst books dedicated to identity beyond the binary are immensely important – C*NDY does not attempt to discuss the achievements of the LGBTQ+ community. C*NDY is instead ‘a project for all’, in particular ‘anyone who felt othered by their freedom of expression’. It is about fashion, makeup, and hair, in a landscape that goes beyond the gender binary. This is a welcome space of indulgence, through the prism of LGBTQ+ identity.

Sophie Lay, English Faculty Library

Serano, Julia. Whipping Girl : A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity. Second ed. Berkeley, 2016.

HQ77.9 SER 2016

A foundational text in transfeminism, Whipping Girl by the biologist Julia Serano is available to loan from the English Faculty Library. The book is described in its tagline as “a transsexual woman on sexism and the scapegoating of femininity”.

The copy we have at the EFL is actually the second edition, which was published in 2016 (10 years after the original). In that time, the book has become a key text (not, Serano notes, the only perspective!) on discussions surrounding gender, queer theory, and feminism. However, as the author says herself in the preface to the second edition: “While the major themes that I forward in Whipping Girl remain just as vital and relevant today as they were when I was first writing the book, some of the specific descriptions and details will surely seem increasingly dated as time marches on.” (p.X).

Despite this, I found myself drawn to discussing the book during LGBTQ+ History Month because of how important this text has become. One of the key elements of this collection of essays and slam poetry is its conception of trans-misogyny: the dangerous blend of both oppositional and traditional sexism (Serano’s phrases), as well as the fact this this book is credited for the popularisation of cis terminology (e.g. cisgender, cissexual, cissexism, etc.). Another important highlight for me is a staunch defence of femininity, and an examination of both the derision of the feminine and accusations of its superficiality and performativity.

It’s hard for me to go too much deeper into the issues of the book without simply parroting all of Serano’s ideas, so I’ll leave off with a quote from the introduction that I believe provides a good baseline for the book:

“One thing that all forms of sexism share – whether they target females, queers, transsexuals, or others – is that they all begin with placing assumptions and value judgements onto other people’s gendered bodies and behaviours.” (p.8)

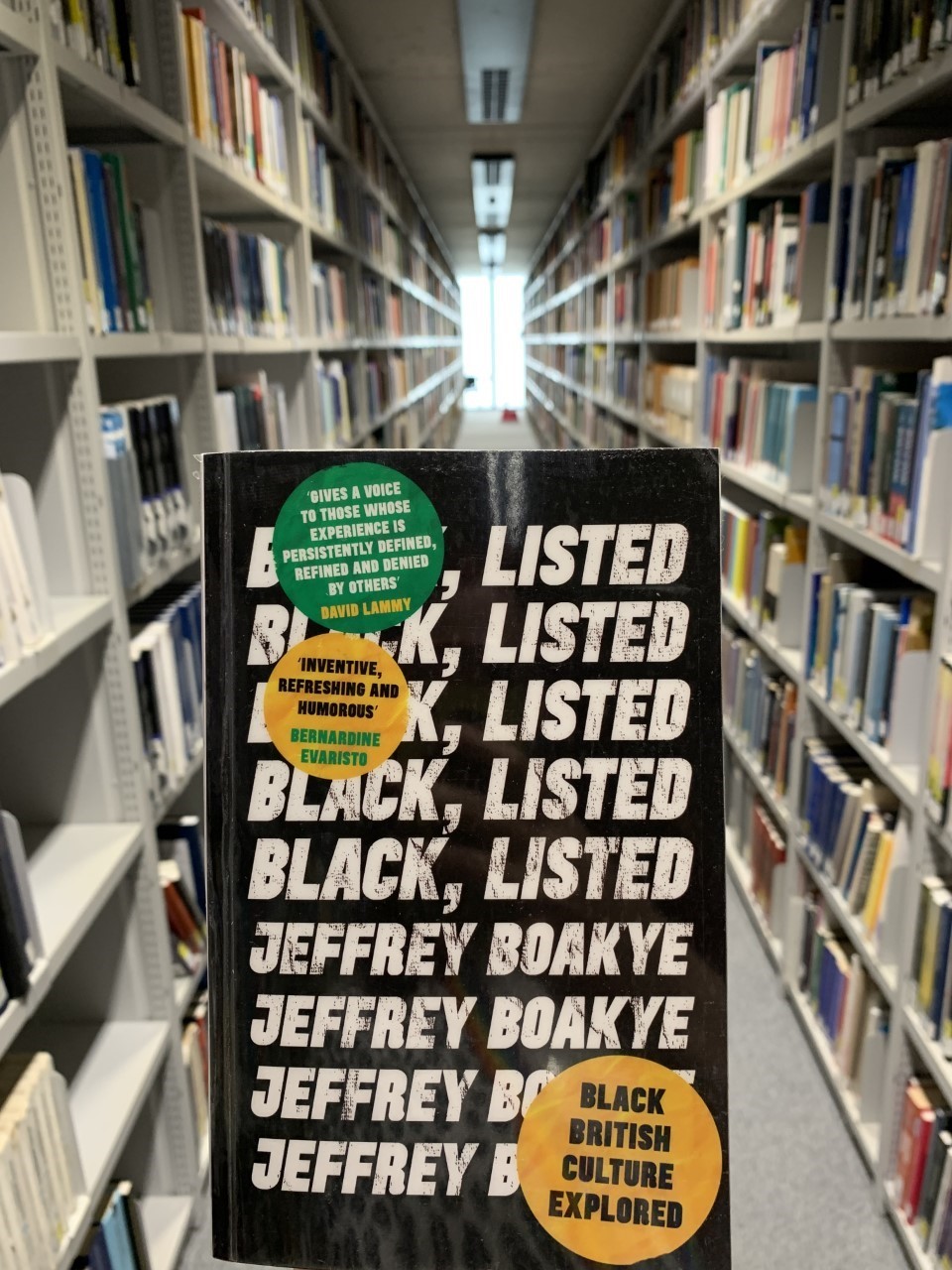

Eleanor Winterbottom, St Antony’s College Library

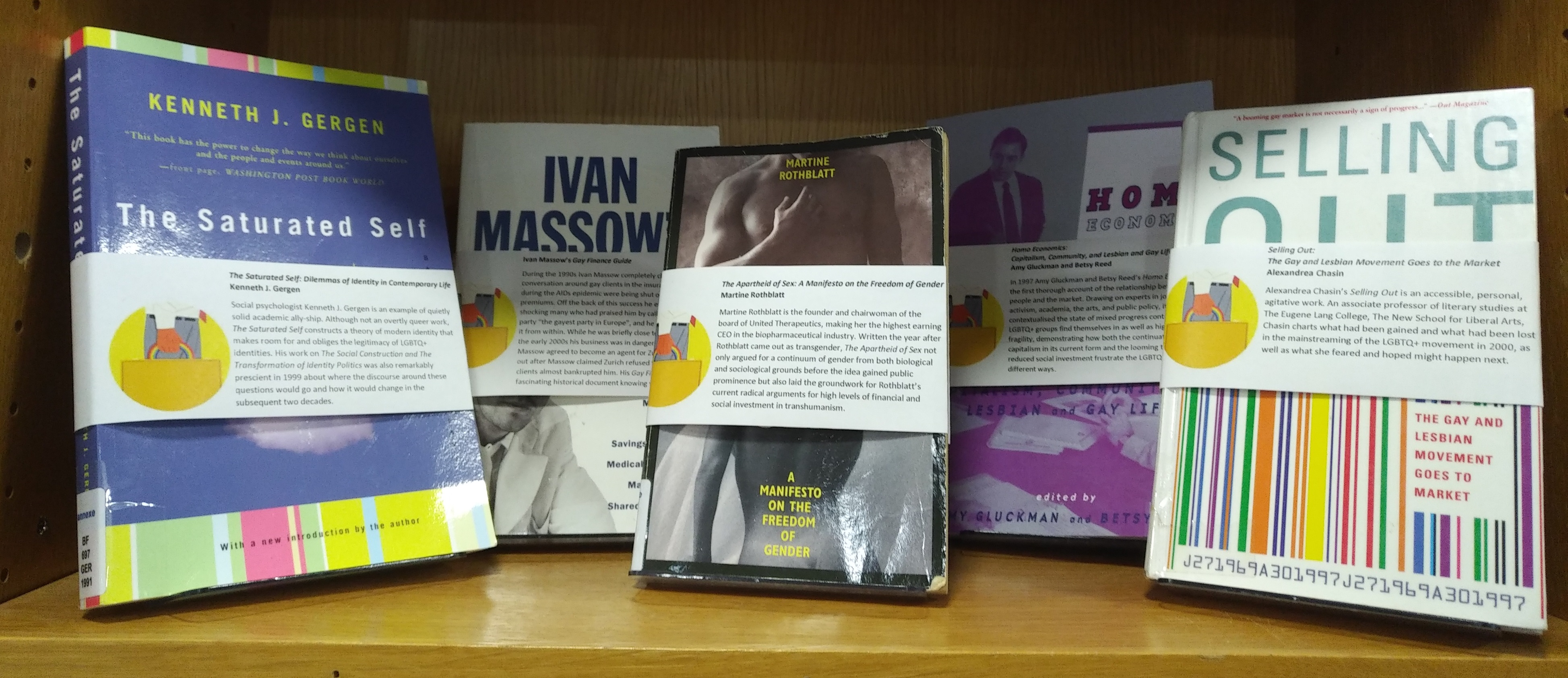

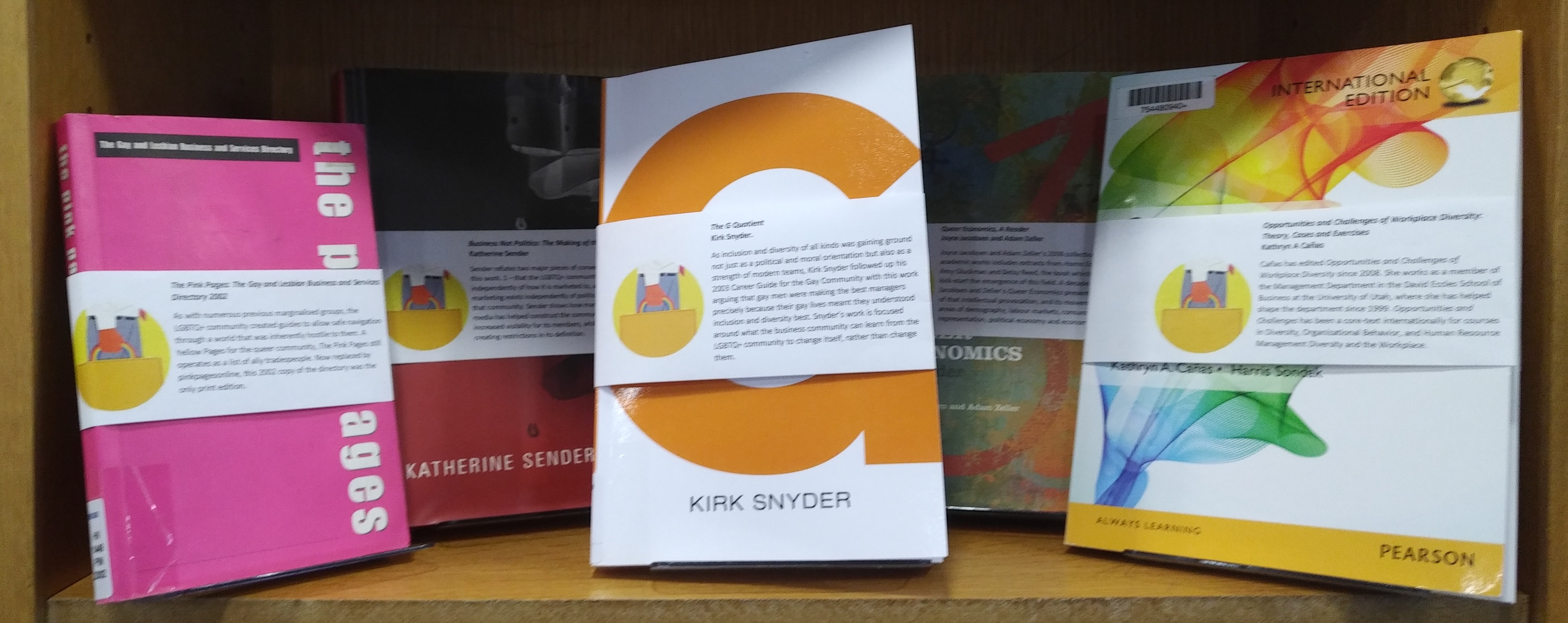

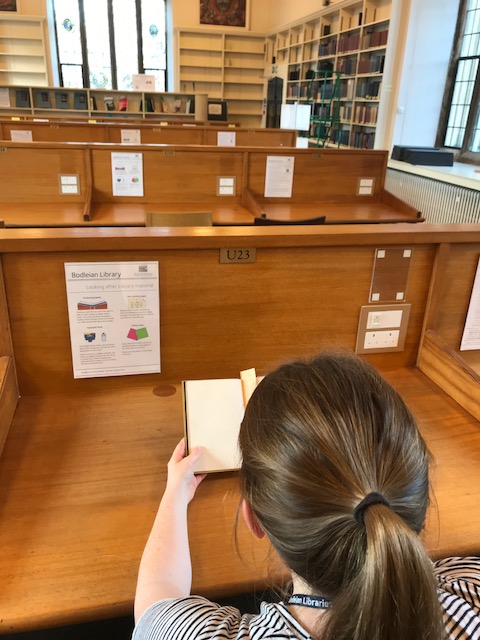

St Antony’s College Library LGBTQ+ History Month Display

At St Antony’s College library our collection covers a wide range of material on the social sciences, international politics, economics, anthropology, history, and culture. This means we were quite spoilt for choice when selecting material for LGBTQ+ history month! When creating our display, we wanted to make sure we showcased the best of what our collection has to offer on this subject and draw attention to the ways LGBTQ+ history is interconnected with, and relevant to, so many different areas of study.

Our display includes material that talks more broadly about the economic, political and international aspects of LGBTQ+ history, such as M.V. Lee Badgett’s the Economic Case for LGBT Equality and Cynthia Weber’s Queer International Relations, to material that focuses on the experience of the individual like Amrou Al-Kadhi’s Life as a Unicorn. We also wanted to ensure that our material covered history and culture from multiple parts of the world, so we have included books on LGBTQ+ history in China, Russia, the US, Africa, Latvia, the UK, India, and more.

Creating this display has been a fascinating and inspiring experience. The vast amount literature written about LGBTQ+ history from multiple areas of study just goes to show how important this history is when it comes to gaining a better understanding of the world and the human experience. It is crucial that we continue to showcase and celebrate LGBTQ+ voices, stories, and history, and I look forward to seeing our LGBTQ+ history collection grow and flourish in the future!

Books referenced:

Recent Comments