During the odd lunchtime during term, the Upper Library at Christ Church becomes host to pop-up displays of special collections material. Part of my Graduate Trainee role that I’ve really enjoyed is assisting with these displays, whether through invigilation, talking with visitors about the collection or selecting texts for display. Today I’ve put together a selection of texts that featured in our display on Early Modern conceptions of skin. Through the lens of travel books, anatomical texts and medical manuals we invited visitors to explore a range of cultural and medical understandings of skin during this period. I’ve chosen just three items from this display to share in this post today – read on for fugitives (of a kind), duels, and medical drama…

Johann Remmelin’s Catoptrum Microcosmicum

It’s possible that one comes across most lift the flap books during childhood. Literary giants such as Eric Hill’s Spot Bakes a Cake[1] come to mind. In this charming story flaps serve as an important ingredient of the mischief and excitement of the book. A flap that takes the form of a wave of chocolate cake batter can be lifted by the intrepid reader to reveal Spot stirring up a storm beneath, for example.

Much to my dismay, we do not hold Spot Bakes a Cake in our collection at Christ Church, but that does not mean we are completely bereft of lift the flap books. Despite Abe Books listing this as the ‘Original Lift the Flap’, there are in fact earlier examples of such a technique, and one such text featured in our display.

Johann Remmelin’s Catoptrum Microcosmicum (Augsburg, 1619) is the first anatomical atlas to use flaps to illustrate layers of anatomy. Instead of joining Spot in his mission to bake a birthday cake for his dad, you are invited to step into the shoes of the 17th century physick, learning about the intricacies of the muscles, bones and beyond of the human body. The plates show first a male and a female figure surrounded by figures of isolated body parts, including the eye, ear, tongue and heart. All of these are represented at their different levels with flaps – the man and woman to a depth of 13 superimposed layers. Each new layer reveals what can be found in the body at different stages of a dissection.

A later edition of this text, published in 1670, sets out on the title page that this book contains:

‘an anatomie of the bodies of man and woman wherein the skin, veins, nerves, muscles, bones, sinews and ligaments are accurately delineated. And curiously pasted together, so as at first sight you may behold all the outward parts of man and woman. And by turning up the several dissections of the paper take a view of all their inwards’ [2].

The flaps themselves are referred to as ‘dissections’ here, the act of the reader lifting a flap becoming amalgamated with the incision of the anatomist’s scalpel. ‘Curiously pasted together’ is a good description – the nature of the ‘lift the flap’ anatomy book imbues the medical diagram with an enact-able curiosity that only increases with interaction with the different layers.

Despite my attempts to tip the balance with this blog post, when it comes to breath-taking 17th century anatomical books, the phrase ‘lift the flap’ is not bandied around with much regularity. Strange! Rather, they are grouped within a pioneering class of anatomical print known as the ‘fugitive sheet’ or ‘compound situs’. This technique is first recorded as being seen in 1538 in works by Heinrich Vogtherr, which made use of layers of pressed linen[3] to create the same effect we see in Remmelin’s Catoptrum Microcosmicum.

These fugitive sheets would have been a fantastic way for users to understand the internal workings of their bodies, even without proximity to a cadaver. However, writing about Remmelin’s anatomised Eve, one commentator notes how the figures in these engravings ‘[sit] amid the horrific attributes of sin and death […]. If this is self-knowledge, one might prefer extroversion.’[4]

Gaspare Tagliacozzi’s De curtorum chirurgia per insitionem

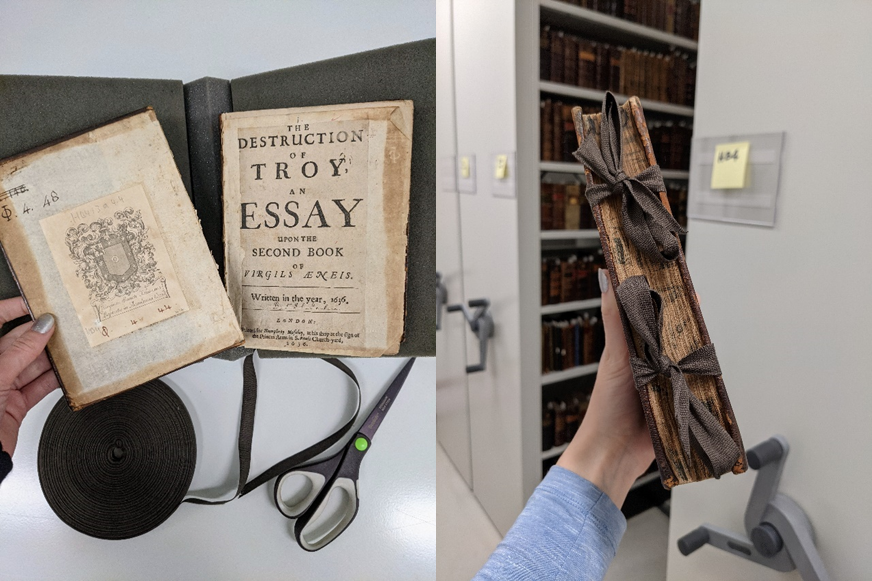

Also included in our display was Gaspare Tagliacozzi’s De curtorum chirurgia per insitionem (Venice, 1597). The copy held at Christ Church is a pirated edition of the first book devoted entirely to plastic surgery. In fact, multiple un-official editions of this text appeared soon after the original due to its popularity[5].

The realities of plastic surgery met a real need in the 1500s, largely because duelling and violence were pretty rife. If you had taken a rapier to the face in a duel for your honour (perhaps your reputation is on the line when the last slice of chocolate cake has disappeared and you are found with crumbs round your mouth) a spot of light plastic surgery might be just what you’re after.

Around thirty years before Tagliacozzi wrote De curtorum chirurgia per insitionem, the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe was taking some time out from considering the stars and turned to the far more terrestrial pursuit of losing his nose in a duel against Manderup Parsberg, his third cousin. While he and Parsberg later became friends, Tycho was landed with wearing a prosthetic nose for the rest of his life. Word on the 16th century street was that this prosthesis was crafted from finest silver, but when Tycho’s corpse was exhumed in 2010, it was a brass nose that was found, not silver.[6]

While coming a little too late to be of use to Tycho, Tagliacozzi’s text focuses on the repair of mutilations of the nose, lips and ears, using skin grafts in an operation that became known as the ‘Italian graft’. This technique allowed for facial reconstruction via a skin graft taken from the left forearm. The graft would remain partially attached to the arm while grafted to the mutilated area so the skin cells would not decay. Tagliacozzi’s talents did not stop at medical innovation however – he also had an eye for (practical) fashion. Due to the importance of the patient being able to hold their arm to their face after the surgery to facilitate the complete adherence of the graft, Tagliacozzi designed a complex vest, not unlike a straightjacket, to make sure there was no unwarranted movement. The process was supposed to take from two to three weeks.

William Cowper’s Anatomia corporum humanorum

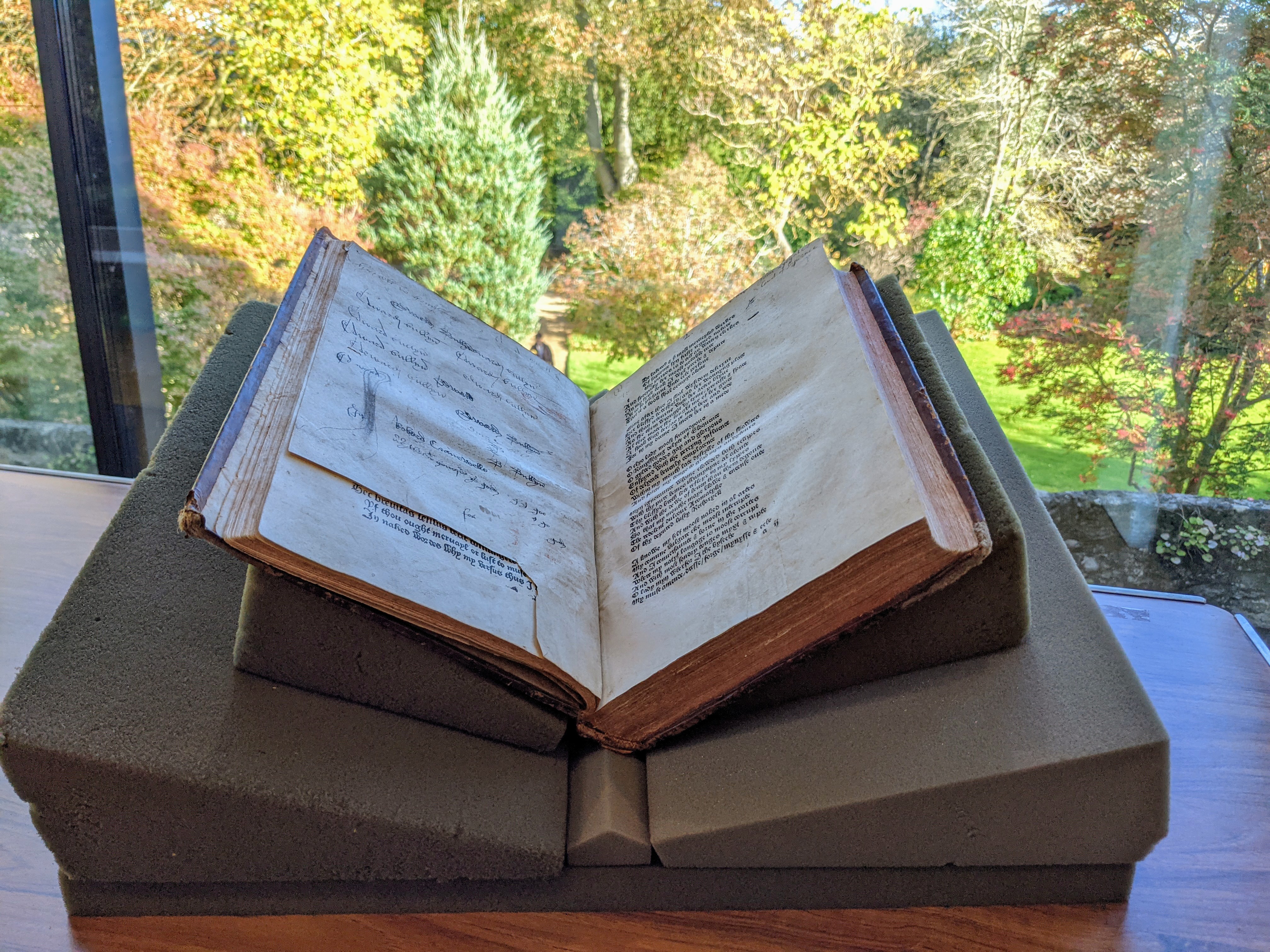

The final book that will feature in my post today is William Cowper’s Anatomia corporum humanorum (Leiden, 1750) and at the heart of this text is one of the most famous controversies in medical history.

The plates that feature in Anatomia corporum humanorum were not originally produced for this text, but rather the earlier Anatomia humani corporis, by Govard Bidloo (1649 – 1713). Originally published in 1685, Anatomia humani corporis features 105 striking copperplate engravings of the human body. The plates illustrate the muscular, skeletal, reproductive, and systemic organization of the human body and are seen alongside scientific commentary.

An English contemporary of Bidloo, William Cowper, bought the printing plates from the printing house and reissued them under his own name with new accompanying text in his Anatomy of humane bodies. A text that, in a profound lack of tact, also featured ‘numerous harsh criticisms towards Bidloo’s contributions’[7]. Unlike today, plagiarism – especially over national boundaries – was largely tolerated at the time, as it was difficult to police. Bidloo objected strongly to this instance of plagiarism from Cowper, however, promptly and publicly excoriating him in a published communication to the Royal Society.

What could be termed as Cowper’s lack of imagination when swiping someone else’s prints was more than made up for by Bidloo’s creative insults in this pamphlet – on one occasion calling him a ‘highwayman’, and another a ‘miserable anatomist who writes like a Dutch barber’[8]. I think I’d rather be on the anatomist’s table than have such lines about me circulating in print. All’s fair in love and science I suppose…

The plates in question were produced by the Dutch painter Gerard de Lairesse. For Lairesse, the anatomical illustrations commissioned by Bidloo were an opportunity for an artistic reflection on anatomy. They are very different from the tradition kick-started by the Vesalian woodcuts in De humani corporis fabrica[9].

Lairesse displays his figures with a tender realism and sensuality, which at first glance seems unfitting for an anatomy book. The figures seem docile, as if in a light sleep rather than deliberately posed objects of scientific inquiry. In these illustrations dissected parts of the body are contrasted with soft surfaces of un-dissected skin and draped material. Flayed, bound figures are depicted in ordinary nightclothes or bedding, as if they will soon be put back together again and woken up.

That’s all I’ll share today – I’m off to make a case for Spot Bakes a Cake as being a prime investment for Christ Church library’s collection.

References

[1] https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/122786/spot-bakes-a-cake-by-hill-eric/9780723263586

[2] https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo2/A93593.0001.001/1:1?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

[3] Find out more here! https://artsci.case.edu/dittrick/2014/06/26/flipping-through-anatomical-fugitive-sheets/

[4] Review: Paper Bodies, by Mimi Cazort https://www.jstor.org/stable/41825971?seq=4

[5] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24610608/

[6] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Tycho-Brahe-Danish-astronomer/Mature-career

[7] https://digex.lib.uoguelph.ca/exhibits/show/bidloo-and-cowper–anatomists-/the-beginnings-of-conflict–pu

[8] https://digex.lib.uoguelph.ca/exhibits/show/bidloo-and-cowper–anatomists-/criminis-literarii–anatomists

[9] https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/358129

Recent Comments