On Wednesday 26th October the 22-23 Trainees had their annual Book Storage Facility Tour. As this blog has seen a good 12 years of posts about the facility (we’ve been visiting since its grand opening in 2010) this year we thought we might do something a little different. Rather than wax lyrical on its 11m tall shelves (which would stretch 153 miles end to end) and its incredible collection of around 12 million items, we thought we’d start a little smaller and look at the life cycle of a single, solitary BSF book.

Ingenious Ingesting

New books first arrive at the BSF through the Delivery Room and then progress onto the Processing Floor to undergo the process of ingestion. No, this has nothing to do with any bodily functions (thankfully), instead it’s the term we use to describe an item being welcomed into the Bodleian’s collections. For our book, this means first being given an all-important barcode. Barcodes are to Librarians what ear tags are to animal conservationists, we use them to track the movements of our respective objects of study. Without this barcode it would be impossible to find the item once it disappeared onto the near endless shelves of the BSF. Barcodes are assigned to books based on how they were acquired, barcodes starting with a number 7 are legal deposit items, and non-legal deposit books will start with either a 6 or 3.

Now that our book has a barcode attached to it, its height is measured, and it’s placed into a special paper box with other books of the same size. Our book gets only the best as this box is made of special acid-free paper sourced from Germany. The handle is also a specially made plastic, tested thoroughly to ensure that it won’t melt in a fire. The BSF has thousands of these incredible boxes across the site, and its one poor person’s task to take the flat nets and build them up into boxes. I’m told it’s one of the riskier jobs on the rota given the likelihood of vicious and painful paper cuts.

With our book safely nestled in its new home it’s time to go through some more scanning. Having already had a barcode stuck to its front cover and scanned into the system; the book now has its barcode scanned again to attach it to the barcode of the box it’s sitting in. It goes through this process not once, but twice, to ensure it’s not missed the first-time round. This method of grouping books into boxes based on their height rather than their contents may seem to be a textbook case of judging a book by its cover, but I can assure you that the BSF isn’t organising its books this way just to fit in with the latest BookTok trends. There is a logic to this madness.

Organising the books by height, as some storage-savvy librarians may already have guessed, is the most efficient way to

make use of the space. Rather than one shelf accommodating books ranging in size from the tiny ‘Old King Cole’ (clocking in at a miniscule 0.9mm) to the unwieldy ‘Birds of America’ (an impressive 1×0.72m in size), the shelves at the BSF maximise their use of space and ensure no large gaps are left from having to accommodate books of diverse sizes. A further benefit to mixing up the collections this way, is that should the unthinkable ever happen and disaster strike, causing damage to some of the books, you’re less likely to lose an entire curated collection all at once. Happily, this is not something the BSF has ever really had to worry about, as it has a stellar record on the safety and well-being of the books in its care (12 years and no major incidents!)

So, it is with great care that various boxes of books are loaded up onto one of the building’s many forklift/cherry-picker hybrids and chauffeured into their new position atop one of the many towering shelves inside the BSF. Our books travel in style as the machine they are transported on is carefully designed to assure a smooth ride between the very narrow aisles of the BSF. The floor is laced with a magnetic wire that guides the machine with pin-point accuracy between the shelves to ensure there are no unfortunate accidents á la Rachel Weisz in her ground-breaking role as Evelyn Carnahan in The Mummy. Once our book has arrived safely in its place it is scanned once more to connect it with the barcode number for its specific shelf, then it goes into a cosy hibernation, waiting quietly for a wandering reader to stumble across its SOLO (Search Oxford Libraries Online) record and make a request.

Daring Deliveries

When this occurs, it’s time for our book to spring back to life. Its name will make a list of VIP books for collection, generated 6 times a day. If it makes that list before 10:30 it will likely be delivered the same day, any later and turnaround extends into the next day. Once the list has been picked, the book makes a return journey via cherry picker back to the Processing Floor where it is packaged into a special blue tote (fancy librarian name for a box)

labelled with the name of the library where our reader wishes to receive it. That tote is then loaded onto a van (which runs this route twice a day) and then starts this mass migration of books from Swindon into Oxford. The van deposits the books at Osney where they are sorted into two further vans with different routes. Regardless of which route they take, our books will arrive at the library in good time for the reader to access them for whatever essay, tutorial or exam they might be taking part in.

Before the reader can access the book however, they need to know it is there – that’s where we librarians come in. At the Radcliffe Camera and the Old Bodleian, we receive deliveries sometimes as often as twice a day, although for most other libraries the frequency is a little slower. When those deliveries arrive, we must safely guide the delivery van into place, then carry all the boxes back and forth (being careful not to mix books returning with books arriving). The totes are carefully packaged so as not to be too heavy to carry but many are still hefty, clocking in at roughly 10-15kg each when full. Once the delivery is unpackaged, we gently scan each book and check it is correctly tagged for its reader to find with a Self-Collect slip, and then shelve it accordingly.

Once its reading period is over, the librarians will remove it from the shelves and begin the whole migration process in reverse. Upon their arrival back at the BSF, the books are sorted according to their barcode numbers, packaged back into the correct boxes, and returned to hibernation to await their next adventure.

Scrutable Scanning

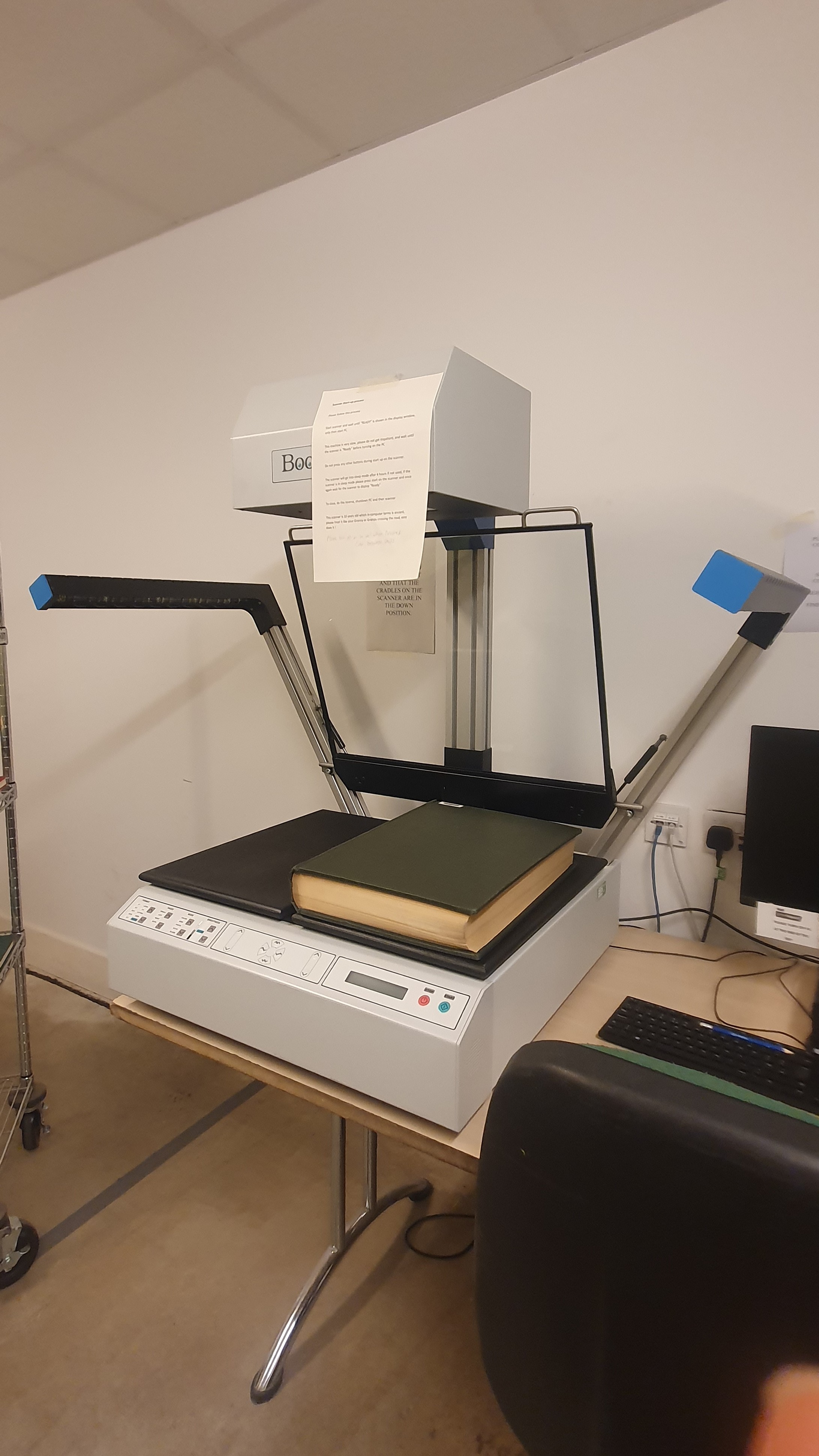

Another important aspect of the BSF book life cycle is scanning. For books that cannot undertake the twice daily migration another option is available, as the BSF has been offering a ‘Scan and Deliver’ service (clearly named for all the Adam and the Ants fans out there) since 2012. Once again, our book will be placed on a special list, picked from the shelves according to the barcodes listed for its location and taken to a special room inside the BSF designed entirely to accommodate the massive amounts of scanning that takes place. The BSF is the most efficient of all the libraries’ locations in terms of scanning, and they are proud to note that they average around 45,000 pages scanned a month. It’s no doubt then that the staff in charge of scanning at the BSF are highly skilled at handling these books.

When scanning commences, each item is carefully lifted from its place on the scanning shelf and laid to rest in a special BookEye scanner. These scanners are specially designed to work with the book’s physiology and allow it to be scanned without damaging its spine or any other vital organs such as pages or binding. The book is then pressed gently underneath a sheet of glass and a bright light runs across it, logging every curve and line of the text within. The pages of the book are delicately turned, and the process repeated for every required page. A skilled scanner can complete an entire chapter without distressing the book at all. Once all the requisite information is recorded the book is lovingly returned to its nest in the bowels of the BSF.

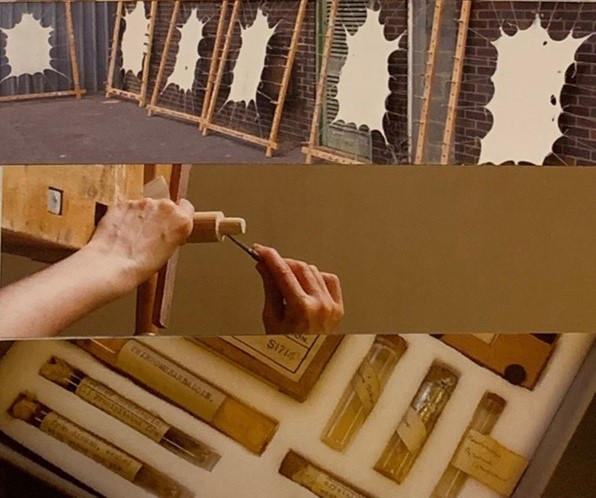

Dastardly Dangers

So far you can see that the books within the BSF are incredibly well cared for and face little in the way of existential threats. In fact, many of the natural predators of the book are managed by the BSF in such a way that they pose little to no threat at all.

One of the most prescient threats to the lives of our books is the risk of fire. Thankfully the BSF has ensured our books are safe from harm in that respect, they’re kept safe by massive 4-hour fire walls (and 2-hour fire doors) to minimise the risk of fire spreading from one book settlement to the next. There’s also an incredibly sensitive air sampling system connected to the building’s sprinklers and two massive tanks of water ready to extinguish any flame the moment it sputters to life. Despite its sensitivity, the sprinkler system has only ever had one false alarm in 12 years. The poor books caught in the ensuing deluge were diligently dried out by an outside firm and then returned happily to their respective nests in the store (although a few items still have visible watermarks from the incident).

Another potential danger to our books is pests. Many a librarian has known the horror of leafing through the pages of a book, only to find they have been nibbled on by a parasitic visitor. However, thankfully, conditions at the BSF are such that they discourage other forms of life from outstaying their welcome. The rooms are temperature controlled to a perfect 18°C and the lack of moisture and other food sources mean that any adventurous animals that might find their way in, such as woodlice or flies, often die off fairly quickly in an environment that is perfectly suited for nourishing books but hostile to pretty much everything else. This being said, pest control still makes a visit to the BSF every 5 weeks or so just to ensure no intrepid insects have braved the harsh conditions to gorge on the juicy pulp of book paper.

Thanks to these careful measures, the life expectancy for books at the BSF is long and it’s rare for books to die of unnatural causes under their care, so we can rest easy in the knowledge that the books under that big warehouse roof will have a long and happy life.

Recent Comments