As part of my traineeship at the Weston Library, I’m undertaking a project to improve access to the Broxbourne collection—some 4000 items, including 2000 specimens of fine binding from the 12th to 20th centuries, donated by John Ehrman in 1978 in memory of his father, Albert Ehrman. The project has two major objectives: capturing high-quality images of these excellent examples of bookbinding, making them available online on a public platform; and writing the copy-specific notes for each book in ALEPH (our library management software) so that they are searchable on SOLO. To date, over 350 books and their descriptions are available on the Bodleian Rare Books Flickr page.

The latest batch of uploads (the capture process is always evolving) clock in at around 100MB per photo, and are available for download in high resolution. From elaborate Grolieresque gold-tooled bindings to outstanding examples of blind-stamped religious panels from England and the Netherlands, the Flickr platform is so far a visual success. This is due (in no small part) to the nature of the collection: Albert Ehrman amassed one of the greatest collections of fine bindings in Britain. Many possess fascinating provenances, such as a presentation copies (Broxb. 24.3, bound for Robert Dudley with his bear-and-ragged-staff emblem, comes to mind), or even a book whose boards have been hollowed out to house a dead man’s will (Broxb. 14.8). Some exceptionally beautiful items include embroidered bindings (typically executed to a pattern, but unique each time), books with painted enamel plates (Broxb. 12.16), and several fine Louvain ‘Spes’ panels.

At the start of my traineeship, I loved books and appreciated a good binding, but was inexperienced in describing them, let alone in recognising ‘sixteenth century Saxon pigskin, rebacked’. Even the best compendia of bookbindings rely strongly on an informed readership, taking for granted many bibliographic terms and descriptions. Six months ago, when I began my traineeship, I had no idea what most of these things meant. The Flickr project has been a revelation, providing visual reference-points for these often complicated descriptions—and I hope that it will be useful to others in this way, too.

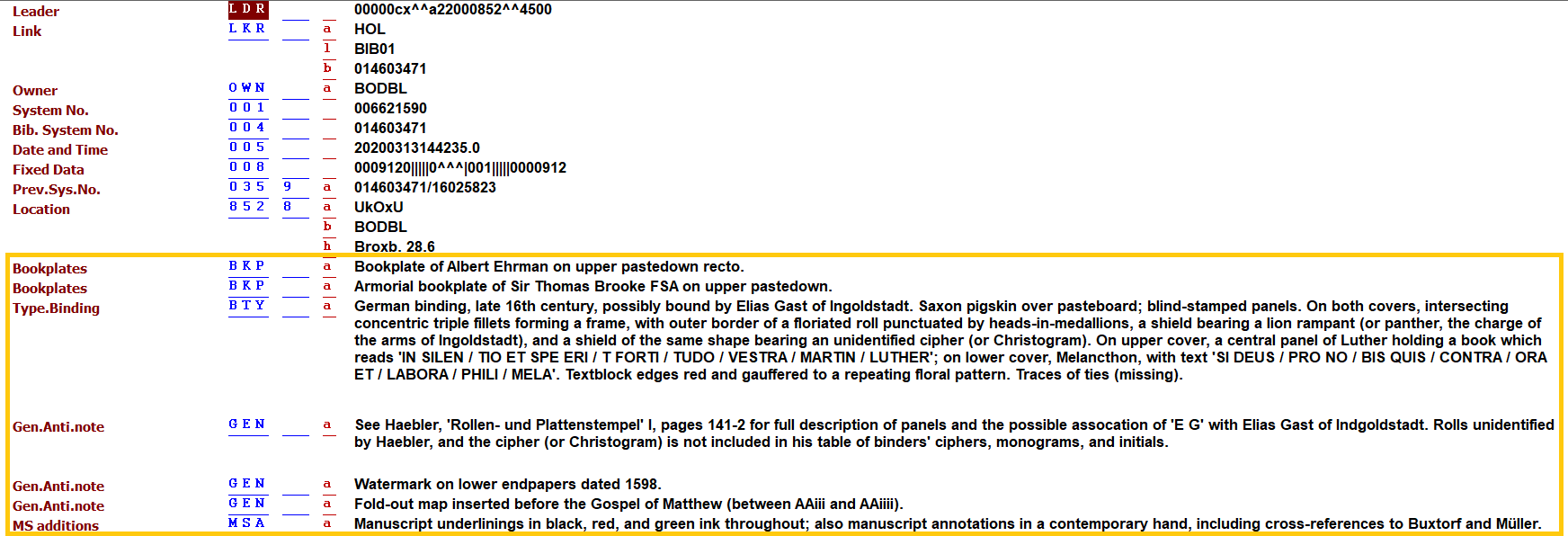

Nevertheless, even the copious eye-candy that digitising provides does not make a collection ‘accessible’. Our Flickr platform is designed to complement—not replace—the proper catalogue records (no matter how good it might look!). Physically, these books are still located in the Weston Library’s vast underground stacks, sitting in grey conservation-grade boxes. This isn’t to say that Broxbourne has been underappreciated (it hasn’t, and great studies of bookbinding have been written about it) but we want them to be found by anyone, not just the specialist who already knows where to look. Albert Ehrman’s books are a highly valuable scholarly resource which can contribute to research not only about bindings, but also into the book trade, ownership, art and cultural taste, and so on. To that end, all the information they contain must be findable as metadata in the Bodleian’s library catalogue. Writing copy-specific descriptions for these books continues the work of the incomparable Paul Morgan, who compiled the card index to Broxbourne in the 1980s, and is a matter of putting in all the valuable information (such as its country of binding, time period, material, style, provenance, and bibliographic references) to transform the findability of our records. Here’s a Broxbourne record, with all the new bibliographic data highlighted in yellow:

Before, there were no descriptive elements; anyone looking for ‘lions rampant’ would have missed Broxb 28.6. The metadata simply wasn’t there. It’s a bit dramatic—but not too much of a stretch—to say that a significant amount of Ehrman’s collection, beyond the really famous stuff, would have gone to waste. And that’s only if you know what you’re looking for!

Another, major advantage to taking libraries into online spaces is the ability to share resources and research. Even in these early stages of the Broxbourne project, we’ve been enabled to bolster our own records (and even challenge assumptions written about binders in the bibliographic canon) thanks to other projects—notably the British Library Bookbindings Database, Philippa Marks’ exemplar after which many decisions about my own project have been modelled. The short version of one of our best discoveries is that Broxb. 24.4 was bound by the ‘Salel’ binder not Etienne Roffet—a discovery that would not have been possible without digitised resources (see below).

I would encourage anyone with a manageable selection of books, especially fine bindings, to consider creating a digital collection. In this, I’m guilty of propping up a bad habit of ignoring trade bindings and cheaper books, but, as is widely known, finer books are more likely to survive (and carry their artistry, provenance, waste paper, marginalia, and all manner of treasures with them). As a teaching resource they have great potential to provoke an interest in materiality and histories; as topics of academic research there is great benefit to a system that allows straightforward and immediate side-by-side comparison (not in the least because many are too fragile to handle regularly). And they’re even nice to look at on a rainy afternoon at home, when a global supervirus threatens life as we know it.

Follow the Broxbourne Project here.