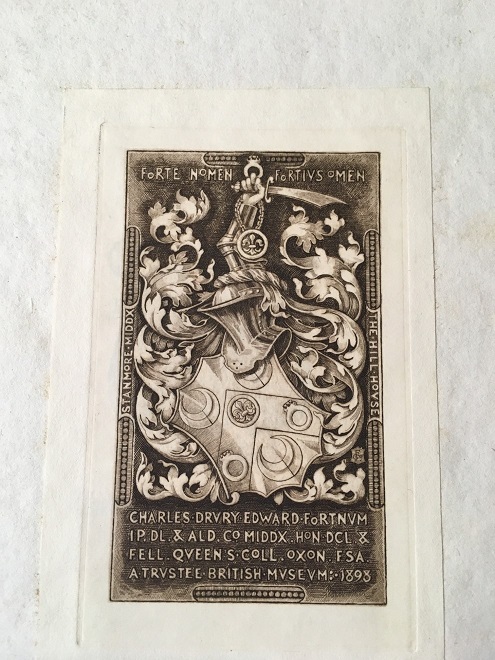

With elaborate gilt-lettered red leather bindings and coarsely cut pages, the Histoire de l’art chez les anciens held in the Sackler Rare book room is the final in a series of five French translations of Johann Joachim Winckelmann‘s seminal work, Geschichte der kunst des Altertums, (History of the Art of Antiquity) published between 1766 and 1802. The front cover of each of these volumes bears the bookplate of the connoisseur and fellow of Queen’s College, Oxford, Charles Drury Edward Fortnum (1820–1899), an avid collector of sculptures, bronzes, maiolica and rings, and described in his obituary as the ‘second founder’ of the Ashmolean Museum.[1]

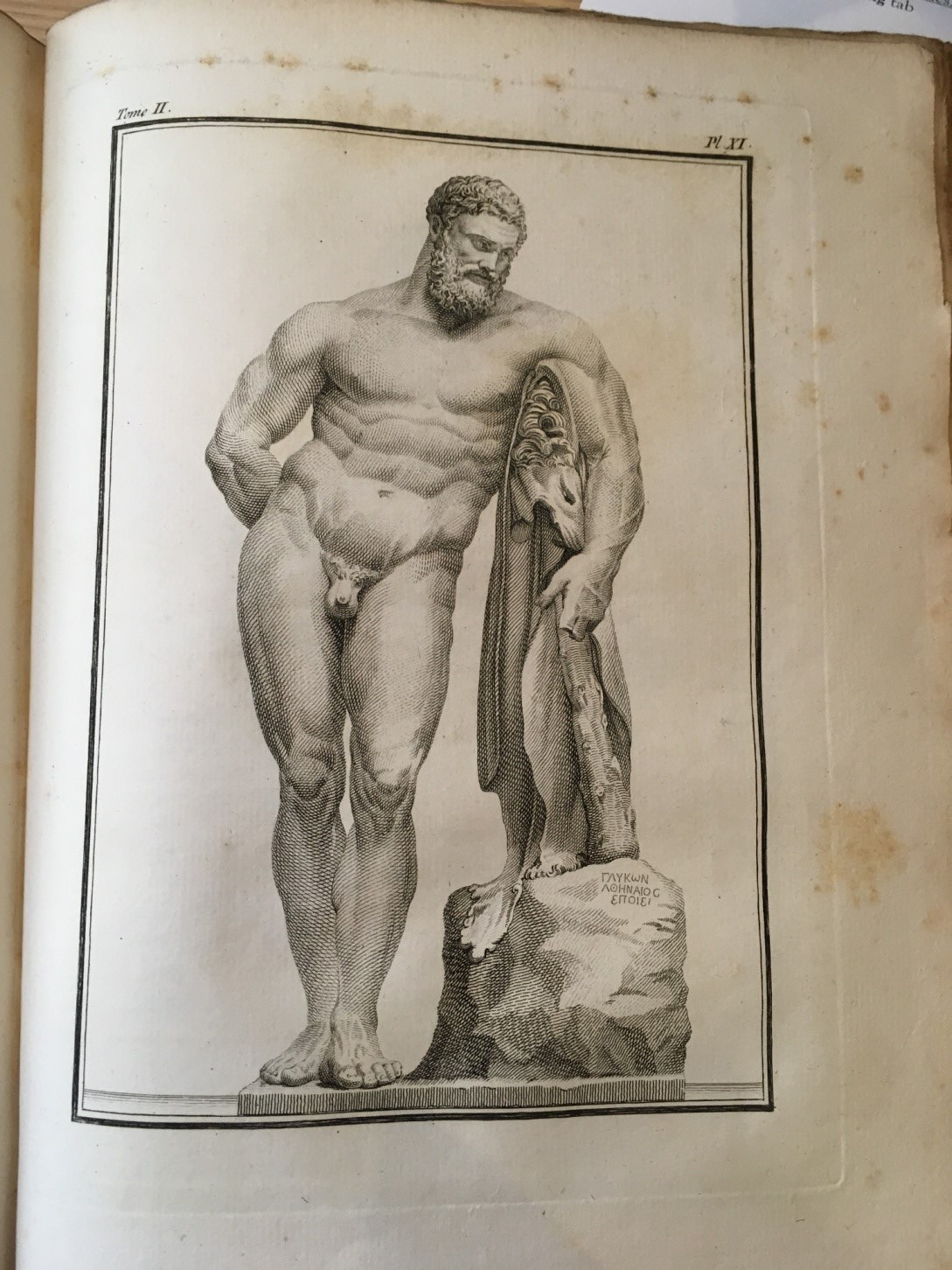

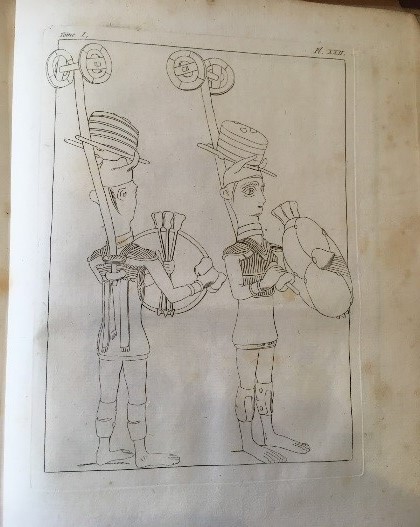

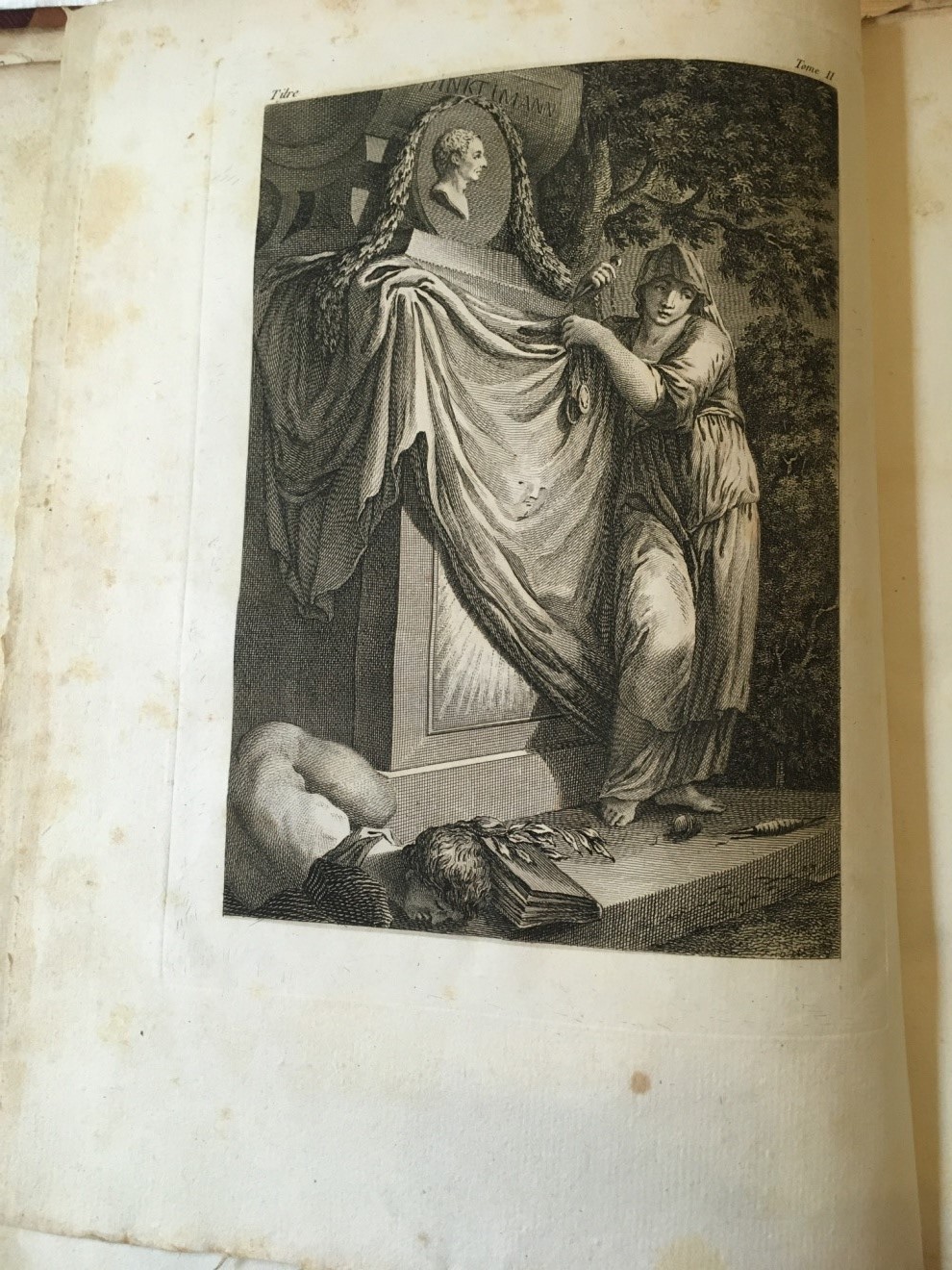

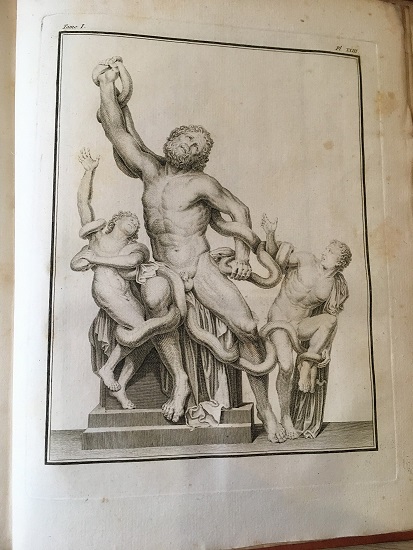

A striking feature of this richly illustrated three-volume edition is the variety and quality of the images used throughout the work. Found at the beginning and end of each chapter and in the appendices to each volume, these pictures include finely-rendered engravings of ancient coins, bas-reliefs, ancient sculptures, objets d’art, landscapes in the style of Piranesi, and detailed architectural plans. Some of the statues depicted are instantly recognisable as the emblematic monuments of antique sculpture that Winckelmann described in the Historie. Others are obtuse, bizarre, and even ugly objects, lightly sketched, or densely rendered. Each item is meticulously described and annotated in an extensive appendix that makes up a substantial part of the third volume.

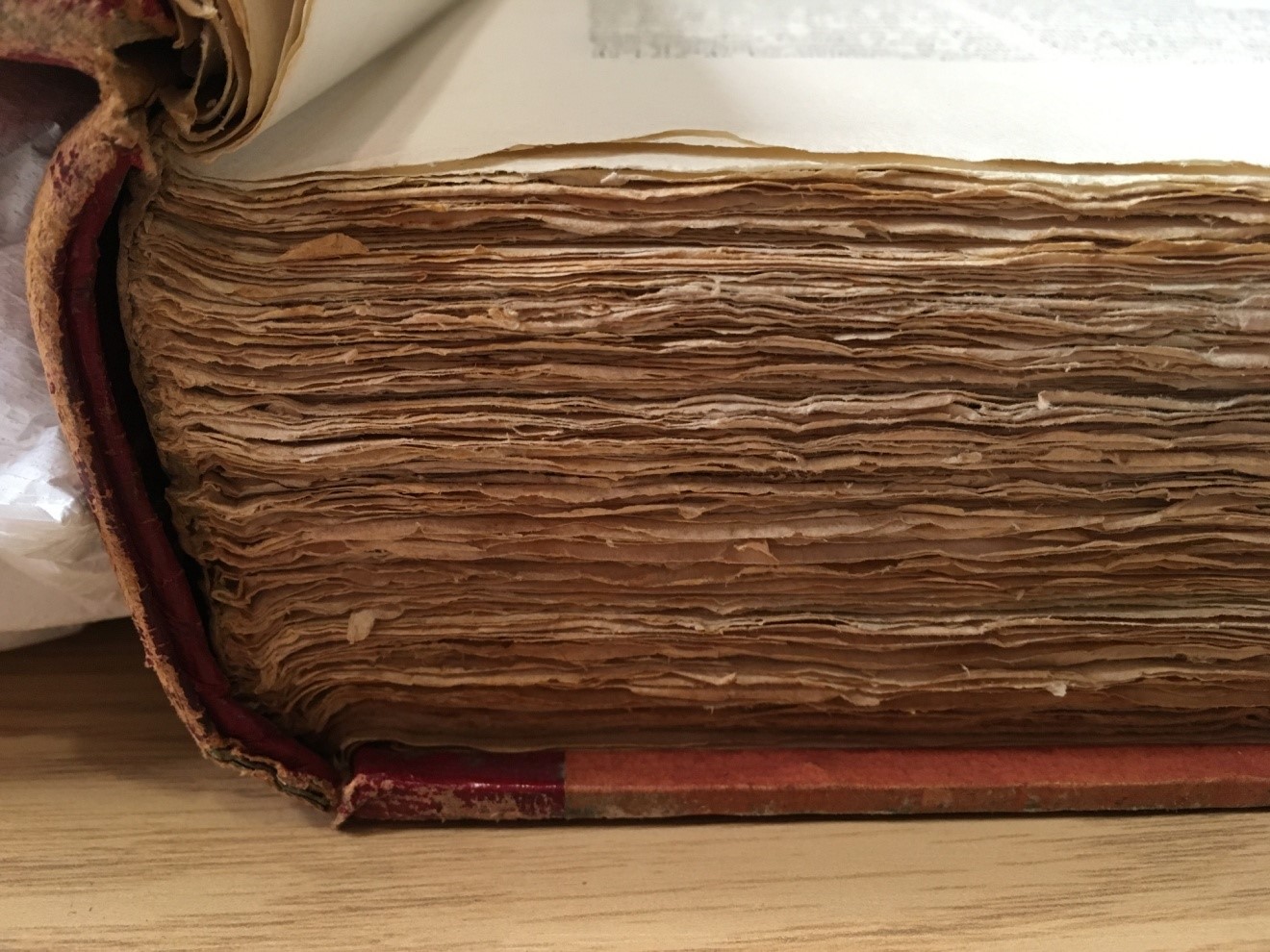

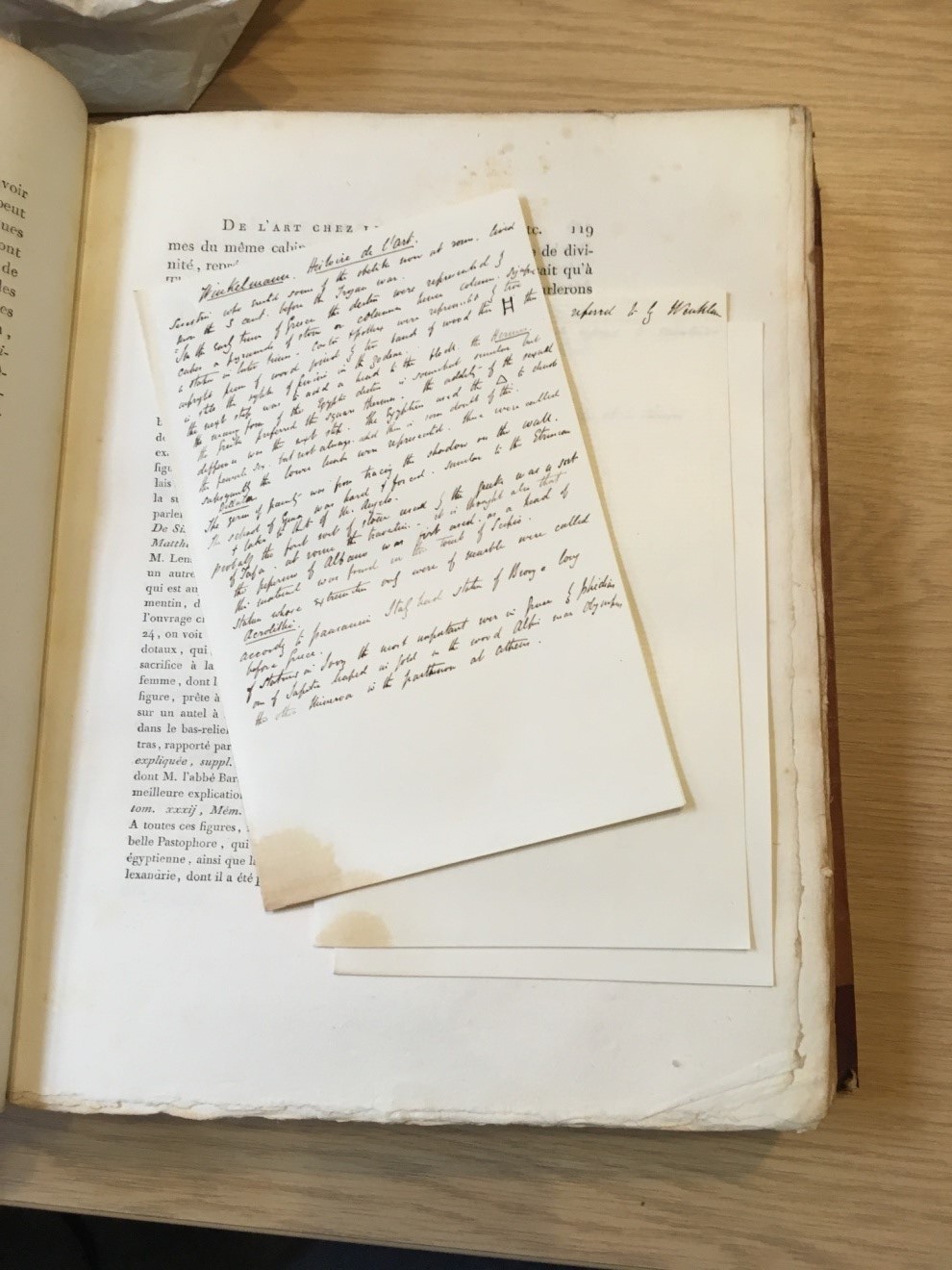

Beyond their immediate intellectual and historical significance, these volumes are sensually captivating for the bibliophile. Ephemera such as the carefully handwritten notes of past scholars, the uncut pages, the bookplates, the Ashmolean museum stamp, and the flimsy tissue paper that protects each of the plentiful illustrations, convey a sense of the book’s material presence. These objects integrate the memory of past scholarship into the aesthetic experience of engaging with the Histoire, and provide a physical and visual testament to the continued fascination of Winckelmann’s work for nineteenth-century connoisseurs and collectors.

Winckelmann, born in 1717 in Stendhal, became one of the most celebrated figures in Europe through his writings on classical art, directing popular taste towards the Greek ideal and influencing not only Western painting and sculpture, but also literature and philosophy. These volumes provide an insight into the complex and important history of Winckelmann’s publication in France.

Winckelmann himself was responsible for the first translation of the Geschichte into French. Keen to promote and disseminate the work around educated circles of Europe he arranged for the Histoire to be printed in France in 1766, only two years after its original publication in German in 1764.[2] His impatience, however, resulted in a botched translation, and Winckelmann had to pull on his connections in Paris and their influence with the police to suppress and confiscate copies of the failed work.[3]

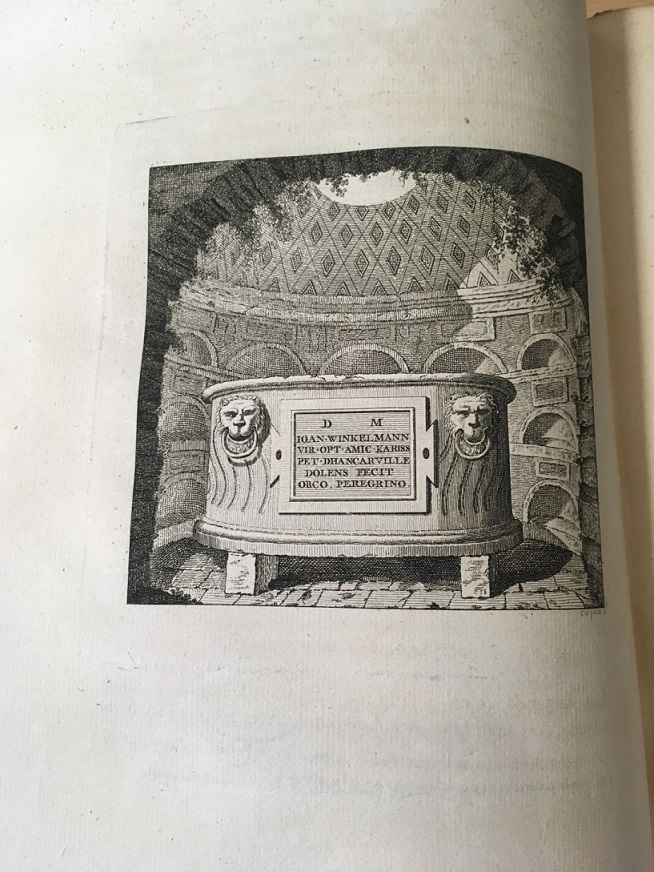

The sensational and grisly nature of Winckelmann’s murder in Trieste in 1768 along with the quality and comprehensive nature of the Histoire itself and its broader significance in laying down the intellectual framework for the disciplines of Art History and Archaeology, ensured that the work found a ready audience in the artistic and connoisseurial circles of Europe. A second edition, with a translation by Michael Huber, was published in 1781, which was popular enough to justify the printing of a new edition and translation in 1786. In 1786 Winckelmann’s Treatises on Taste, the Recueil de différentes pièces sur les arts, which included such essays as the Sentiment for the Beautiful in Art, and Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture were also translated and published. These works include some of Winckelmann’s most famous rhetorical writings on classical statuary such as the Laocoön, the Apollo Belvedere and the Niobe.

Winckelmann’s influence in France is evident from the wide-ranging references to him in the art dictionaries and the costume dictionaries of late eighteenth-century France. The popularity of his work was increased with the publication of a new version of the Histoire in 1794 at the height of the Terror, with this final edition being published in 1802-3.[4] In this context it is interesting to note that there was no English translation of the Geschichte until the 1850s.

The 1794 and 1802 editions were produced by the Dutch bookseller, revolutionary and freemason Hendrik Jansen. In 1799 Jansen also published Winckelmann’s Treatise on allegory in French as Essai sur l’allégorie, à l’usage des artistes. He was an important factor in the dissemination of Winckelmann’s work, and was among the first to recognise the significance of Winckelmann’s works being read in their entirety rather than in extract form. Jansen’s activities as a publisher and translator also helped to bridge the gulf between art theory and every-day artistic practice by stressing the practical use of Winckelmann’s knowledge and expertise.

The quantity of editions produced of the Histoire de l’art in France demonstrates that there was an ongoing interest and continuing market for Winckelmann’s writings on Greek and Roman antiquities in France before, during and after the Revolution. This was accounted in part by the passionate intensity of debates surrounding the nature of beauty during this period. Even though the most pre-eminent artist of the time, Anton Raphael Mengs and others questioned the accuracy of some of Winckelmann’s attributions, the debate over the veracity of Winckelmann’s work demonstrates how seriously it was taken by the artistic establishment in France. Winckelmann and the Histoire came to represent a detached and authoritative voice in the debate surrounding beauty to which contemporary theorists such as Mengs, the Italian archaeologist Carlo Fea,[5] the German writer and philosopher Gotthold Lessing,[6] and the German classical scholar and archaeologist Christian Heyne responded in these Sackler editions. The lavish attention to the illustration and presentation of these volumes, the dedicated scholarship and densely printed essays written by these leading art theorists, provide a window into the art theoretical and antiquarian debates of late-eighteenth-century France, and the value they attached to Winckelmann’s monumental achievement in writing a trajectory of the history of ancient art.

Fiona Gatty, Research Fellow (DPhil, History of Art, 2015)

We welcome suggestions for future blog contributions from our readers.

Please contact Clare Hills-Nova (clare.hills-nova@bodleian.ox.ac.uk) and Chantal van den Berg (chantal.vandenberg@bodleian.ox.ac.uk) if you would like propose a topic.

[1] Timothy Wilson, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/9951

[2] This version was published by Charles Saillant with a translation by Gottfried Sell.

[3] Despite this there is a copy of the 1766 version in the Bodleian Weston Library.

[4] Of these five translations the most widely circulated was the three-volume French translation by Michael Huber, published by Henrik Jansen in Paris in 1790-4. Potts.1994. 256. Ft.4

[5] Fea was responsible for a very popular translation of the Geschichte into Italian, Storia delle Arti del disengo presso gli antichi, which was published in Rome in 1783-4. ibid. 256. Ft 9.

[6] Lessing’s most significant art theoretical text was Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry.