The Bodleian Art, Archaeology and Ancient World Library’s Haverfield Archive is perhaps best described as an assortment of archaeological paraphernalia. From coloured prints to illustrations of mosaic pavements, site plans and publications the archive has the potential to serve as a great source of information for researchers working on Roman Britain. In the final post of this series (posts I, II and III were published in 2020), I want to concentrate on why there is an archive in the first place. I believe that this is an important question we should be asking when considering all of these collected documents. When I first viewed the archive in 2019, it was unclear why the notable archaeologist and ancient historian Francis G. Haverfield (1860-1919) had decided to collect images of Roman floor mosaics as well as of related art works and other archaeological discoveries, assembling them within a very particular framework: Sometimes the images are organised according to chronology or geographic location, but also quite frequently their design or iconography is what makes them part of a specific group. The motivation behind the archive appeared to have been lost from social memory and the key players behind it are no longer here to give their reasons. Therefore, our only option is to piece together what clues have been left behind. Haverfield himself also left a text-based archive but this has never been catalogued and there is no finding aid to it; in any event, the Covid lockdown prevented prolonged access during my 12-month graduate library traineeship (September 2019-August 2020), the period when I was examining the collection. Working on archaeological sites, the only clues we have of people from the past are the objects that they have thrown away or accidentally lost. Since there may have been a reason why documents were grouped together in specific ways, I made sure that the Haverfield floor mosaic images were identified as belonging to the same assemblages in which I found them.

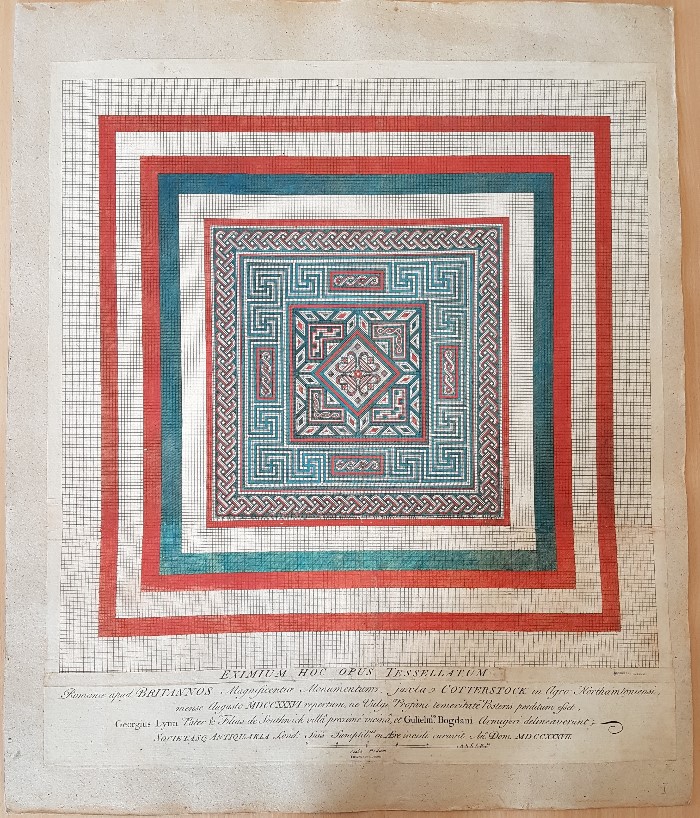

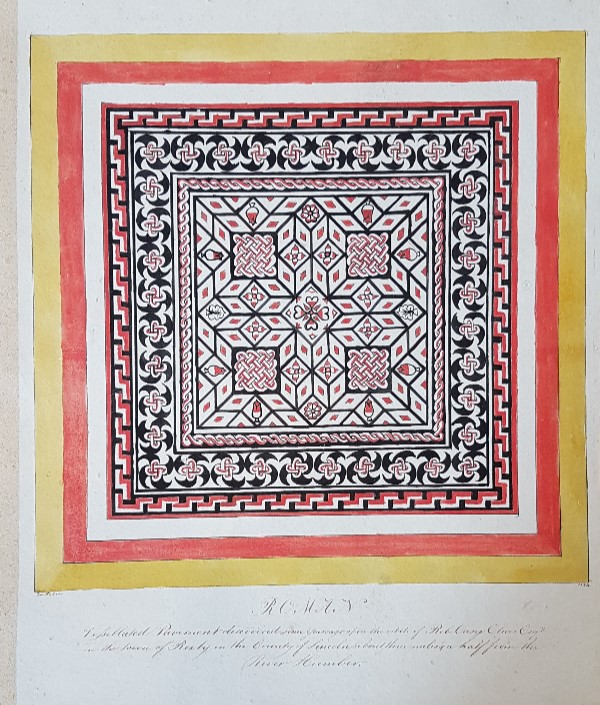

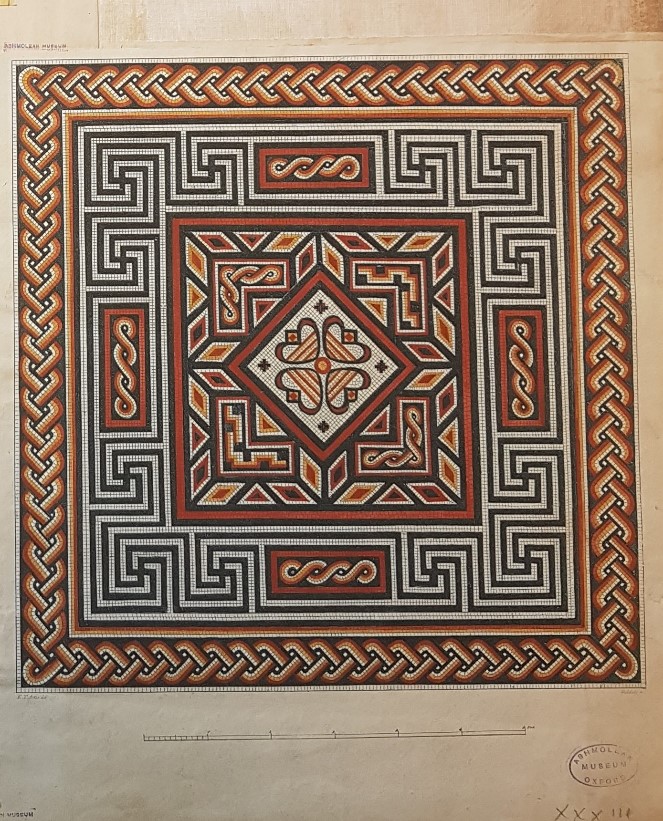

Throughout his life, Haverfield remained convinced that archaeology needed better funding. As mentioned in the first post, in his will he left his papers and books to the University of Oxford. After his death in 1919, Haverfield also left a substantial bequest, for which the University appointed a group of academics to serve as administrators. This group would develop policies for the use of its funds, with the intention of enhancing the study of Roman Britain. This included contributing towards the expense of collecting and preparing materials for publication. These planned projects included A Corpus of Roman Bronzes in Britain and A Corpus of Roman Glass. The prints of Roman floor mosaics in the Haverfield Archive could have been materials gathered for a similar project. It is possible that a group of scholars gathered together prints for an eventual publication, but that the project failed to materialise. With early antiquarian discoveries of mosaics, nobody from the field had really decided to create a nationwide inventory of Roman mosaics in Britain. Haverfield and his associates may have intended to produce this collected inventory.

Haverfield already had connections to the archaeological sites where some of the mosaics originated. For example, the Yorkshire Archaeological Society began another excavation on the Roman remains at Aldborough (for description see blog post II), reportedly under Haverfield’s guidance.

It is possible that Haverfield was using his image collection, along with descriptions from previous sites, to inform his approach to the excavation at Aldborough. In archaeological reports, it is very typical for there to be a description of previous excavations at the same site. In fact, it could have been Haverfield’s intention to include illustrations of the mosaics previously found at Aldborough in a new publication in order to draw attention to Roman archaeology in Britain.

Further evidence of Haverfield’s intention to publish the documents in his visual archive is the presence of several prints of the same floor mosaic found at Stonesfield (see blog posts II and III). By 1713, two influential illustrations of the mosaic were widely available. One of these was the version produced by Thomas Hearne and Michael Burghers, which I discussed in the second blog post in this series. The other illustration was made by Edward Loving and was circulated more widely than Hearne and Burgher’s version. Similar to Hearne and Burgher’s version, Loving’s illustration was presented to the Royal Society in full colour. Loving proposed to the Society that the illustration should be engraved on copper plate. Presumably, the Society was won over by Loving’s persuasiveness and ordered a copy of the illustration to be framed. Reportedly, Hearne disliked Loving’s version of the mosaic as it allegedly had many inaccuracies.

Loving’s version of the Stonesfield mosaic could well be Inventory n. 1.15, as there are handwritten notes on both sides of the print. These pencilled notes include ‘same in Piccino’, ‘For Venice’ and ‘Pitisco Lexicon antiq.’. As arbitrary as these notes seem, they do make sense when context is provided since Loving’s version was republished in later international editions. It was first included as a frontispiece in Samuel Pitiscus’ Lexicon Antiquitatum (Leeuwarden, 1713) and a smaller version of the illustration was made by Suor Piccino in Venice, 1719. Suor Piccino’s version was then copied for a compilation of antiquities by the French antiquary Benard de Montfaucon (1655-1741) for his Antiquity Explain’d (Paris, 1719). This version may be present in the archive since Inventory n. 2.2A also has handwritten notes including ‘From Montfaucon’. The print itself is very similar to Inventory n. 1.15. The evidence of the multiple print versions of the Stonesfield mosaic and how several prints were even annotated indicates that a plan was in place to compare all of these versions. Thus, it is very possible that this material was intended to form a section of work in an eventual publication.

A further indication that materials in this archive were intended to be published, is the way in which Haverfield grouped and presented the images. There are various examples in the archive of mosaic prints being combined onto one large cardboard sheet. Inventory n. 1.6 B is of interest as at the top of one such cardboard sheet where ‘Northamptonshire’ has been pencilled in. It is these examples of assembled images which make the archive unique, as the documents are more than just a collection of images taken from different publications. Similarly, Inventory n. 1.14 also has ‘Northamptonshire 1’ pencilled in the same handwriting. This may reveal some of Haverfield’s approaches to these illustrations. Haverfield may have decided to paste certain prints of mosaics onto the same sheet if they all came from the same county. Indeed, the mosaics featured in Inventory n. 1.6B and 1.14 all came from places in Northamptonshire. The layout of the document may indicate how Haverfield wanted the prints to be arranged for the plates of a future publication.

There are some further instances, where the illustrations have been pasted on both sides of a cardboard sheet. For example, Inventory n. 1.5 has one side featuring the ‘Orpheus’ mosaic from Littlecote Park (see post iii) and the other side is of a mosaic found in Rudge.

Both mosaics were discovered in Wiltshire, further showing how Haverfield continued to collate images in groups of different counties. Inventory n. 1.10 has two sides of beautifully coloured mosaic prints from Castor with ‘Northamptonshire 4’ and ‘Northamptonshire 5’ pencilled on each side. This also illustrates how important the Haverfield Archive is, as we can use it to follow the thought process behind Haverfield’s choices for publication.

There are several exceptions to the geographical approach, suggesting that the way in which Haverfield collated his images was at times completely different. On one side of Inventory n. 1.17 is a print featuring a series of Roman coins at the top, with an image of a mosaic below. It is unclear where exactly the mosaic and the coins are from. The print does provide a clue, with the Earl of Harborough attributed as the patron, as Harborough is a district located within Leicestershire. The print on the reverse shows fragments of painted wall plaster from Aldborough whose design resembles that of floor mosaic patterns. From the description, they appear to be an illustrated plate taken from Henry Ecroyd Smith’s Reliquiae Isurianae.

A contradictory example is Inventory n. 2.2. One side features Edward Loving’s version of the Stonesfield mosaic and the other features a small print of a mosaic from Carthage. Aside from some similarities in iconography, these prints appear to have little to no connection to each other. These are certainly not anomalies. In Folder 3, the first two sheets I indexed comprised both sides having prints pasted on them which also appeared to be unrelated, chronologically or geographically, to each other. It is possible that there were reasons behind each decision to attach a print on the reverse of another one, but such motivations are now lost (or require more in-depth study).

Finally, I wanted to discuss how Haverfield’s theory of Romanization applies to the archive. I introduced the concept of Romanization in the first post of this series. Haverfield sought to elucidate the incorporation of Britain into the Roman Empire, which he viewed as a cultural assimilation rather than enforced acceptance. Haverfield was the first British academic to systematically consider the cultural consequences of the 43 C.E. Roman invasion through archaeological evidence. For Haverfield, this evidence suggested that Britain fully participated in Roman culture. His theory challenged previous views — which reflected British early 20th century colonial values — that it was through invasion and colonisation that Britons became more ‘civilised’ and ‘Romanized’. For Haverfield, therefore, the term ‘Romanization’, therefore, indicated a more ongoing and active process. To him, Roman Britain was not a stage of British history, but rather one of several cumulative parts of the Roman Empire. It is no wonder that he may have developed an interest in Roman floor mosaics, especially if they mirrored similar designs in Imperial Rome.

Haverfield once told an audience ‘It is no use to know about Roman Britain in particular unless you know about the Roman Empire in general’. Roman Britain was not a stand-alone entity but was rather one part of an all-encompassing, global Empire. In order to fully understand Roman Britain, one has also to study Imperial Rome. It is difficult to say whether Haverfield himself was affected by the superior philosophy developed by many affluent gentlemen during the peak of the British Empire. In the third post of this series I discussed how the antiquarians who created illustrations of mosaics which partly constitute the Haverfield Archive may have perceived floor mosaic remains as a tangible link between the British and the Roman Empires. Whilst historians should always seek to remain neutral when exploring the past, it is often impossible to not be influenced by the period of history one is living in.

Haverfield was once quoted as saying that with the Roman Empire:

‘‘Its imperial system, alike in its differences and similarities, lights up our own Empire, for example India, at every turn. The methods by which Rome incorporated and denationalised and assimilated more than half of its wide dominions, and the success of Rome, unintended but perhaps complete, in spreading its Graeco-Roman culture over more than a third of Europe and a part of Africa, concern in many ways our own aged Empire” (Journal of Roman studies, vol I, pg xviii-xix, quoted from Craster, 1920: 70).

To an extent, therefore, Haverfield was making direct comparisons between the Roman and British Empires. Like his contemporaries, Haverfield’s thinking may have been somewhat influenced by colonial attitudes. British imperial expansion combined with an education which sought to celebrate the accomplishments of classical civilisation may have informed his world view. Despite this, it is unclear in the above quote whether Haverfield is explicitly glorifying the British Empire or, rather, condemning it.

The ultimate purpose of Haverfield’s visual archive is not completely clear. Although evidence points towards how Haverfield may have gathered illustrations of archaeological discoveries for a planned publication, it is never explicitly stated that this was his intention. Throughout the process of indexing a small part of this visual archive I felt as if I was following a trail of bread crumbs. Each handwritten note, each new copy of the same print was another crumb of evidence. However, Haverfield’s decision to give his papers, books, and some of his wealth to the University of Oxford in order to enhance the study of archaeology is a clear intention. As mentioned at the beginning of this post, Haverfield was convinced that the discipline of archaeology needed better funding and research. It would not be surprising if he had wanted his life’s mission to continue long after his death. By passing on his knowledge and funds, he would guarantee the continuation of the study of the archaeology of Roman Britain. I hope that now the archive has been advertised through a digital medium, there will be a renewed interest in its contents for future research projects.

This is the final blog post in this series. I would like to thank the Sackler’s Librarian-in-Charge, Clare Hills-Nova, for inviting me to work on this project and providing support and advice throughout. I would also like to thank the Classics and Classical Archaeology Librarian, Charlotte Goodall, for her advice and guidance. Finally, a special thanks to Samuel Bolsover who proof-read all of my work.

Chloe Bolsover

Graduate Library Trainee (2019-2020)

Taylor Institution Library

Learning and Teaching Librarian

Sheffield Hallam University

References

18th September 1903. Yorkshire Archaeological Society. British Architect. 216-217

Craster, HHE. 1920. Francis Haverfield. The English Historical Review, 63-70

Draper, J, Freshwater, T, Henig, M, and Hinds, S. 2000. From Stone to Textile: The Bacchus Mosaic at Stonesfield, Oxon, and the Stonesfield Embroidery. Journal of the British Archaeological Association. 153:1, 1-29.

Freeman, PWM. 2007. The Best Training-Ground for Archaeologists. Oxford: Oxbow Books

Hingley, Richard. The recovery of Roman Britain 1586-1906: a colony so fertile. 2008. Oxford. Oxford University Press

Levine, J. 1978. The Stonesfield Pavement: Archaeology in Augustan England. Eighteenth Century Studies, Vol 11, No. 3. 340-361

Todd, M. 2003. The Haverfield Bequest, 1921-2000 and the Study of Roman Britain. Britannia, Vol 34, 35-40

Title-page of Elmsley’s edition of Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus (Oxford, 1811), one of nearly a million 19th-century books scanned from the Bodleian Library for the

Title-page of Elmsley’s edition of Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus (Oxford, 1811), one of nearly a million 19th-century books scanned from the Bodleian Library for the