‘Yes, wonderful things’(?)

A Book Display at the Sackler Library

By Susanne Woodhouse

In 1922, as Egypt moved towards becoming an independent nation, the tomb of Tutankhamun was discovered at Luxor. The excavation of the tomb by Howard Carter and his team developed into a media event and was photographed by Harry Burton (1879–1940), from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The prints and negatives became part of an archive created by the excavators, along with letters, plans, drawings and diaries. When Carter died in 1939, he bequeathed most of his estate to his niece, Phyllis Walker (1897–1977), including the archaeological records. Following the advice of Egyptologists Alan H. Gardiner (1879–1963) and Percy E. Newberry (1869–1949), who had both been on the team, Walker presented the documentation, with associated copyright, to the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, in 1945. The physical archive remains in Oxford and can be freely explored online, allowing scholars from across the world to continually reassess the burial and its discovery (Rosenow, Parkinson 2022: 8).

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in November 1922, Griffith Institute staff, working with Bodleian Libraries staff, created the exhibition Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive which can be seen at the Weston Library until 5 February 2023. (Fig. 2A). The accompanying publication (Fig. 2B) provides an overview of the archive, featuring 50 key items.

In conjunction with both anniversary and Weston Library exhibition, the current Tutankhamun book display at the Sackler Library (Oxford’s central repository for research publications on Egyptology) showcases a selection of works from its collections (Fig. 1). The items are organised into four thematic groups, with relevant new publications added throughout the duration of the display. Special features of this Sackler book display also include the facsimiles of two drawings by Carter; of Carter’s 1922 excavation diary in which he noted the discovery of the first step of an unknown tomb on 4 November; and of a photo album sold to tourists during the clearance of the tomb (Fig. 3).

The publication group “The Excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb and its finds” sets the scene with the authoritative work The tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen: discovered by the late Earl of Carnarvon and Howard Carter, published in three volumes between 1923 and 1933 by Howard Carter and Arthur Mace (1874-1928). The first volume, opened at page 96 (Fig. 4), features in the centre of the display: here, the reader will find the magic words ‘Yes, wonderful things’, supposedly uttered by Carter when glimpsing, through a small breach in the doorway into the Antechamber of the tomb, and making out, in the flickering light of a candle, golden beds in various animal shapes, exquisite furniture, alabaster vessels and food containers. The b/w photo (Plate XV, opposite page 96) captures Carter’s view. However, according to his Excavation Journal (26 November 1922), held in the Griffith Institute Archive, Carter replied ‘Yes, it is wonderful’, casting doubt on the precise wording of his comment (James 2006: 253); the Weston Library exhibition catalogue leans more towards the version given in the Excavation Journal, written close to the events (Parkinson 2022: 40-41) and not intended for the general public.

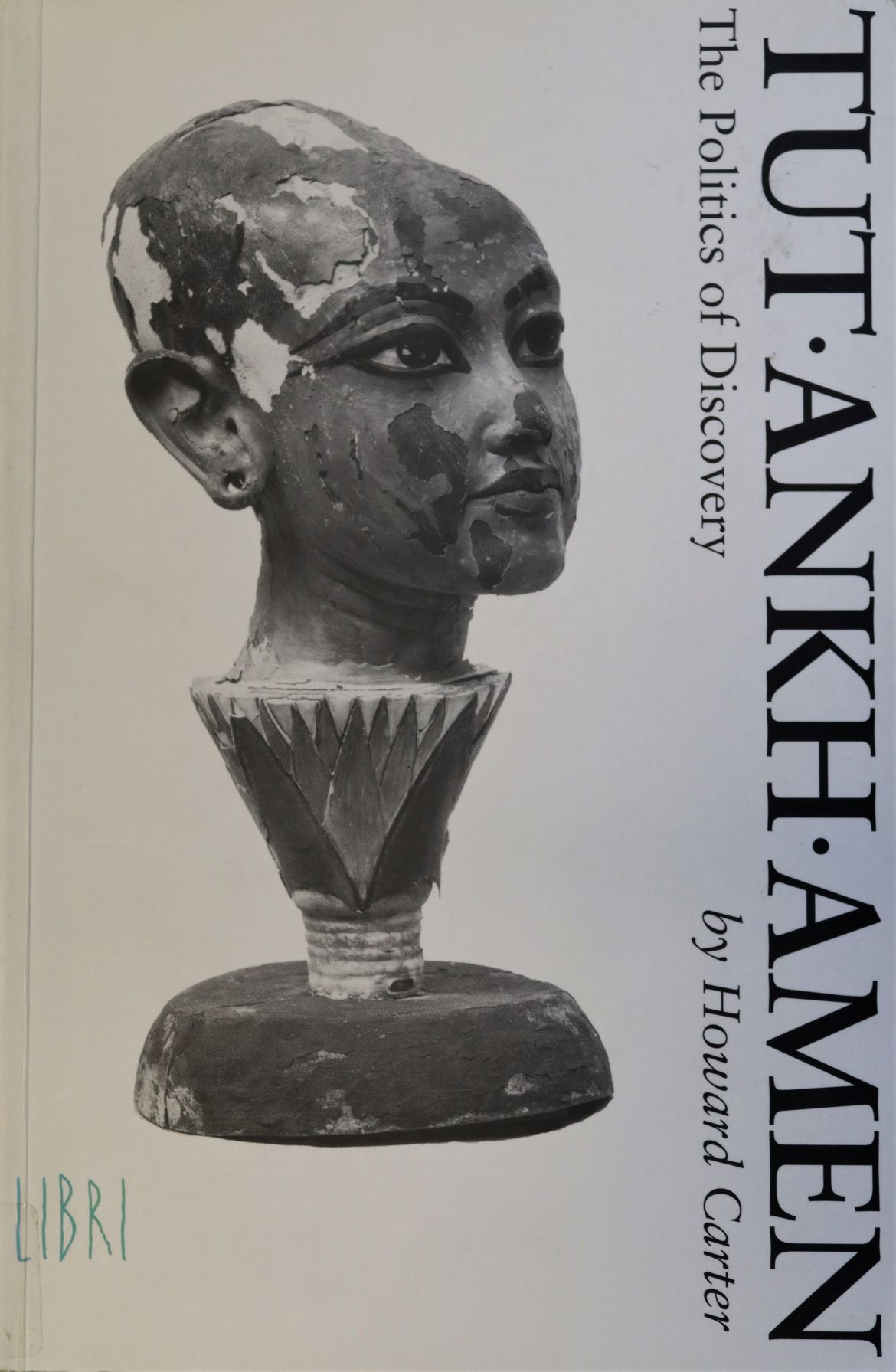

When concerns regarding media access and the constant stream of visitors to the small tomb came to a head between Carter and the Egyptian Antiquities Service in February 1924, Carter and his team departed from the site mid-season, leaving behind the heavy coffin lid hanging from the scaffolding above the coffin. In a statement underpinned by documents for private circulation Carter sets forth his line of action. With only a few dozen copies printed, this historic document was reprinted and introduced by N. Reeves in 1998 (Fig. 5).

These events also feature in a then little-known publication, ‘Schlagzeile Tutenchamun’ in which the author retraces the general media coverage of the discovery of the tomb received in the world press, including in Germany (Fig. 6).

Once recorded by Carter and his team, the finds were crated and shipped to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo at the end of each excavation season, for immediate display. Curious travellers calling on Carter for a tour of the tomb were referred to the Tutankhamun collection at the Egyptian Museum. In 1926 the first catalogue of the permanently displayed objects was published (Fig. 7), serving interested visitors as a gallery guide. Future supplements of the catalogue were to include newly added objects.

The popular account ‘The tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen’ was Carter’s only monograph on this subject. Although he continued adding to the excavation files, the planned multi-volume work dedicated to the finds never materialised. Owning the publication rights, Carter was in a position to ask colleagues for help with this colossal task but it doesn’t seem he ever did. After his death in 1939 the rights, together with his papers, were transferred to his niece who subsequently deeded them to the Griffith Institute in 1945. Finally, in 1951 the first scholarly monograph, dedicated to one object group from the tomb, was published by Alexandre Piankoff, a specialist in religious texts.

In the introduction to ‘Les chapelles de Tout-Ankh-Amon’ (Fig. 8) the author recalls how during WWII the Director General of the Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte suggested he prepare a study of the texts on these four shrines, and how afterwards Oxford-based Alan Gardiner granted Piankoff the publication rights. An expanded English version was published in 1955 (Fig. 9).

In her extensive study of the iconic photographs produced by Harry Burton, Christina Riggs calls them ‘the most famous and compelling archaeological images ever made’ (Fig. 10). She describes the technical aspects of producing glass negatives and the difficult working conditions under which Burton took well over 3,000 shots.

Sumptuous colour images of the objects were published in 2007 in the form of a coffee-table book, the product of a successful cooperation between the photographer Sandro Vannini and the Egyptologist Zahi Hawass (Fig. 11).

Once Carter’s papers and the publication rights were transferred to the Griffith Institute, Alan Gardiner worked tirelessly on having the tomb content published; this is the topic of the second thematic group on display: “Tutankhamun and Oxford”. The Griffith Institute did not have the financial means required for the multi-volume scholarly publication of the tomb finds (Fox 1951: Preface; Eaton-Krauss 2020: 17) and the outbreak of the Egyptian Revolution in 1952 put an end to Gardiner’s efforts to find the necessary funding in Egypt (James 2006: 445; Eaton-Krauss 2020: 217-218).

In 1951 Oxford University Press published ‘Tutankhamun’s treasure’, written by the Griffith Institute’s Assistant Secretary Penelope Fox and highlighting various objects from the tomb (Fig. 12). Although this book was not the ultimate publication Alan Gardiner had in mind, it was the first monograph dedicated to the tomb’s finds produced in Oxford.

Eleven years later the Griffith Institute finally published its first object-focused study. ‘Tutankhamun’s painted box’ is the result of a collaboration between the preeminent copyist and illustrator Nina de Garis Davies (1881-1965), who painted facsimiles of all five decorated surfaces of the box, and Alan Gardiner, who wrote the introduction (Fig. 13).

Finally, in 1963 the Griffith Institute’s Tutʿankhamūn’s Tomb Series (Fig. 14) was launched and a total of nine monographs were published until 1990 when the series was discontinued (Eaton-Krauss 2020: 218-219). Since this date the Griffith Institute has published further definitive monographs on specific object groups from the tomb, though these are no longer part of a series.

Titled “Tutankhamun and the British Museum” the third publication group on display centres on one of the most iconic exhibitions ever shown in the UK. With 1,602,000 visitors, it was the most successful exhibition at the British Museum to date. In 1972, after years of preparations and negotiations, the 50th anniversary of the discovery of the tomb was celebrated with a special exhibition at the British Museum; 50 objects from the tomb were on show, including the golden mask. The cover of the accompanying exhibition catalogue shows an intimate scene between the King and his Queen from a gilded shrine, framed in shades of orange and brown typical for the time (Fig. 15). In a contemporary BBC 4 documentary Magnus Magnusson introduced viewers to the exhibition. The proceeds from this — £600,000 (today’s value £7,6m) — helped pay for the rescue of the temples at Philae (Edwards 1972a: 10; Zaki 2017: 86).

In 1992, the 70th anniversary of the tomb’s discovery, the British Museum showcased Howard Carter’s 30 years of work in Egypt prior to 1922. The exhibition was an academic and popular success (Fig. 16).

Having known families of colleagues as well as close contacts of Carter and having been granted unique access to their papers, T.G.H. James (1923-2009), Deputy Keeper of the Egyptian Department at the British Museum at the time of the 1972 blockbuster, wrote an authoritative biography on Carter (James 2006: Fig. 17). This publication was followed by a lavishly illustrated book in which he discusses objects from the tomb (James 2007).

Aspects addressed in the fourth thematic group on display, “Reception of Tutankhamun”, are Egyptomania (Fig. 18), literature, Egypt’s nationalist movement, and tourism in Egypt in the wake of the discovery of the tomb.

Susanne Woodhouse

Subject Librarian for Egyptology and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

Bodleian Libraries

With the assistance of Jenna Ilett

Graduate Library Trainee

Bodleian Libraries

__________________________________________________________________

References

Eaton-Krauss, M. (2020) ‘Publications in monographic form of the ‘treasure’ of Tutankhamun, 1952-2020′, Göttinger Miszellen, 262, pp. 217-225.

Eaton-Krauss, M. (2014) ‘Impact of the discovery of KV62 (The Tomb of Tutankhamun)’, KMT, 25.1, pp. 29-37.

Rosenow, D. and Parkinson, R.B. (2022) ‘Tutankhamun: The Oxford Archive’, Scribe. The American Research Center in Egypt, 58, 8–11.

Zaki, A. A. (2017) ‘Tutankhamun Exhibition at the British Museum in 1972: a historical perspective’, Journal of Tourism Theory and Research, 3(2), 2017, 80-88. DOI: 10.24288/jttr.312180

Displayed books

Baines, J. and el-Khouli, A. (1993) Stone vessels, pottery and sealings from the tomb of Tutʿankhamūn. Oxford: Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum.

Beinlich, H., Saleh, M. and Murray, H. (1989) Corpus der hieroglyphischen Inschriften aus dem Grab des Tutanchamun : mit Konkordanz der Nummernsysteme des “Journal d’Entrée” des Ägyptischen Museums Kairo, der Handlist to Howard Carter’s catalogue of objects in Tutʿankhamūn’s Tomb und der Ausstell. Oxford: Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum.

Broschat, K. and Schutz, M. (2021) Iron from Tutankhamun’s tomb. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

Carter, H. (1998) Tut·ankh·amen : the politics of discovery. London: Libri.

Carter, H. and Mace, A.C. (1923-1933) The tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen discovered by the late Earl of Carnarvon and Howard Carter. 3 vols. London ; New York: Cassell.

Černý, J. (1965) Hieratic inscriptions from the tomb of Tutʿankhamūn. Oxford: Griffith Institute (Tutʿankhamūn’s Tomb Series ; 2).

Colla, E. (2007) Conflicted antiquities : Egyptology, Egyptomania, Egyptian modernity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Collins, P. and McNamara, L. (2014) Discovering Tutankhamun. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum.

Davies, N.M. and Gardiner, A.H. (1962) Tutankhamun’s painted box : reproduced in colour from the original in the Cairo Museum. Oxford: Griffith Institute.

Dobson, E. (2020) Writing the Sphinx : literature, culture and Egyptology. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press (Edinburgh critical studies in Victorian culture).

Eaton-Krauss, M. and Graefe, E. (1985) The small golden shrine from the tomb of Tutankhamun. Oxford : Atlantic Highlands, N.J: Griffith Institute ; Distributed in the U.S.A. by Humanities Press.

Eaton-Krauss, M. (1993) The sarcophagus in the tomb of Tutankhamun. Oxford: Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum.

Eaton-Krauss, M. and Segal, W. (2008) The thrones, chairs, stools, and footstools from the tomb of Tutankhamun. Oxford: Griffith Institute.

Edwards, I.E.S. (1972a) ‘The Tutankhamun exhibition’, British Museum Society Bulletin, 9, pp. 7-11.

Edwards, I.E.S. (1972b) Treasures of Tutankhamun. London: British Museum.

Fox, P. (1951) Tutankhamun’s treasure. London ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Gabolde, M. (2015) Toutankhamon. Paris: Pygmalion (Grands pharaons).

Germer, R. (1989) Die Pflanzenmaterialien aus dem Grab des Tutanchamun. Hildesheim: Gerstenberg (Hildesheimer ägyptologische Beiträge ; 28).

Haas Dantes, F. (2022) Transformation eines Königs : eine Analyse der Ausstattung von Tutanchamuns Mumie. S.l.: SCHWABE AG.

Hawass, Z.A. and Vannini, S. (2007) King Tutankhamun : the treasures of the tomb. London: Thames & Hudson.

Hepper, F.N. (2009) Pharaoh’s flowers : the botanical treasures of Tutankhamun. 2nd edn. Chicago ; London: KWS Pub.

Humbert, J.-M (2022) Art déco : Égyptomanie. Paris: Norma Éditions

Humbert, J.-M., Pantazzi, M. and Ziegler, C. (1994) Egyptomania : l’Égypte dans l’art occidental, 1730-1930. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux.

James, T.G.H. (2006) Howard Carter : the path to Tutankhamun. Rev, pbk. London: Taurus Parke Paperbacks.

James, T.G.H. (2007) Tutankhamun : the eternal splendor of the boy pharaoh. Rev. Vercelli: White Star.

Jones, D. (1990) Model boats from the tomb of Tuʿtankhamūn. Oxford: Griffith Institute (Tutʿankhamūn’s Tomb Series ; 9).

Leek, F.F. (1972) The human remains from the tomb of Tutʿankhamūn. Oxford: Griffith Institute (Tutʿankhamūn’s Tomb Series ; 5).

Littauer, M.A. and Crouwel, J.H. (1985) Chariots and related equipment from the tomb of Tut’ankhamūn. Oxford : Atlantic Highlands, N.J: Griffith Institute ; Distributed in the U.S.A. by Humanities Press (Tutʿankhamūn’s Tomb Series ; 8).

Málek, J. (2007) Tutankhamun : the secrets of the tomb and the life of the Pharaohs. London: Carlton.

Manniche, L. (1976) Musical instruments from the tomb of Tut’ankhamūn. Oxford: Griffith Institute (Tutʿankhamūn’s Tomb Series ; 6).

Manniche, L. (2019) The ornamental calcite vessels from the tomb of Tutankhamun. Leuven: Peeters (Griffith Institute publications).

Matḥaf al-Miṣrī (1926) A short description of the objects from the tomb of Tutankhamum now exhibited in the Cairo Museum. [Cairo: Egyptian Museum].

McLeod, W. (1970) Composite bows from the tomb of Tut’ankhamūn. Oxford: Griffith Institute (Tutʿankhamūn’s Tomb Series ; 3).

McLeod, W. (1982) Self bows and other archery tackle from the tomb of Tutʿankhamūn. Oxford: Griffith Institute (Tutʿankhamūn’s Tomb Series ; 4).

Murray, H. and Nuttall, M. (1963) A handlist to Howard Carter’s catalogue of objects in Tutʿankhamūn’s tomb. Oxford: Printed for the Griffith Institute at the University Press by V. Ridler (Tutʿankhamūn’s Tomb Series ; 1).

Otto, A. (2005) Schlagzeile Tutenchamun : die publizistische Begleitung der Entdeckung und der Ausräumung des Grabes von Tutenchamun. Marburg: Tectum.

Parkinson, R.B. (ed.) (2022) Tutankhamun : excavating the archive. Oxford: Bodleian Library.

Piankoff, A. (1951-1952) Les chapelles de Tout-Ankh-Amon. Le Caire: Impr. de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale (Mémoires publiés par les membres de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire ; t.72).

Piankoff, A. and Rambova, N. (1955) The shrines of Tut-Ankh-Amon. New York: Pantheon Books (Bollingen Series ; 40:2).

Quaegebeur, J. and Cherpion, N. (1999) La naine et le bouquetin : ou l’énigme de la barque en albâtre de Toutankhamon. Leuven: Peeters.

Reeves, N. (1990) The complete Tutankhamun : the king, the tomb, the royal treasure. London: Thames and Hudson.

Reeves, N. and Taylor, J.H. (1992) Howard Carter before Tutankhamun. London: British Museum Press for the Trustees of the British Museum.

Reid, D.M. (2015) Contesting antiquity in Egypt : archaeologies, museums & the struggle for identities from World War I to Nasser. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

Riggs, C. and Wace, R. (2017) Tutankhamun : the original photographs. London: Rupert Wace Ancient Art.

Riggs, C. (2019) Photographing Tutankhamun : archaeology, ancient Egypt, and the archive. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts (Photography, history: history, photography).

Riggs, C. (2021) Treasured : how Tutankhamun shaped a century. London: Atlantic Books.

Tait, W.J. (1982) Game-boxes and accessories from the tomb of Tutʿankhamūn. Oxford: Griffith Institute (Tutʿankhamūn’s Tomb Series ; 7).

Vartavan, C.de. and Boodle, L.A. (1999) Hidden fields of Tutankhamun : from identification to interpretation of newly discovered plant material from the Pharaoh’s grave. London: Triade Exploration (Triade Exploration’s opus magnum series in the field of Egyptology ; 2).

Veldmeijer, A.J. (2010) Tutankhamun’s footwear : studies of ancient Egyptian footwear. Norg, Netherlands: Drukware.

Vogelsang-Eastwood, G., Hense, M. and Wilson, K. (1999) Tutankhamun’s wardrobe : garments from the tomb of Tutankhamun. Rotterdam: Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn & Co’s.

Wilkinson, T. (2022) Tutankhamun’s trumpet : the story of ancient Egypt in 100 objects. London: Picador.