‘I was her first “reader”, and I would draw’, writes Hélène de Beauvoir (1910-2001) in Souvenirs (De Beauvoir, 1987, p.72), where she recalls how, in the early years, she came to choose the vocation of artist, whilst her elder sister, Simone (1908-1986), preferred to write.

| De Beauvoir, S. and H. de Beauvoir, 1967. La femme rompue. Title page. Paris: Gallimard. W.J. Strachan Collection, Taylor Institution Library, Oxford |

Many years later, shortly after giving a speech on the subject of women and creativity during a visit to Japan in 1966 (Francis, Gontier and De Beauvoir, 1979, pp.458-474), the author of Le deuxième sexe (Gallimard, 1949) wrote to her younger sister with an invitation to create a series of engravings based on her new novel, La femme rompue (Gallimard, 1967). Although Gallimard initially hesitated to take on the project, over fears of it being a rather controversial piece of literature, the completed work, including its illustrations, was finally published in 1967 and also appeared in Elle magazine’s October-November issue of that year (Weber-Feve, 2010, p.82).

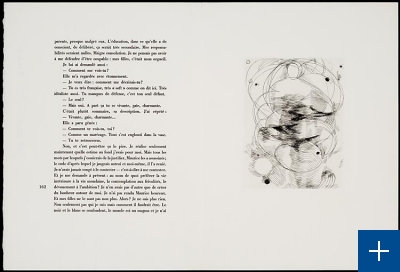

De Beauvoir, S., and H. de Beauvoir, 1967. La femme rompue, pp. 162-163. Paris: Gallimard. Bodleian Libraries, Oxford. W.J. Strachan Collection. (Image: Koninklijke Bibliotheek/National Library of the Netherlands)

The novel is written in the form of an intimate diary and recounts the experience of a housewife who struggles to come to terms with the sudden discovery that her husband has another woman in his life. The main themes covered in the story are echoed in the individual memoirs of the Beauvoir sisters, with particular regard to their mother’s confined domestic life in their family home in the rue de Rennes, Paris, and Simone’s later experience as the second woman in her relationship with philosopher, novelist and political activist Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980). It is this more personal content in La femme rompue, which drew scathing remarks from (male) critics, who viewed the novel as too autobiographical and less interesting than some of the author’s previous work.

Hélène readily accepted the invitation to create illustrations for her sister’s novel and strongly defended the text against the harsh criticism it received. As an art form, the livre d’artiste (artist’s book) was already well-established by this time, with a long tradition of artists, authors, designers and printers collaborating to produce books that were highly sought after by private collectors and bibliophile societies.

| Twentieth century artists’ books, showing artist-designed bindings. Sir Paul Getty Collection, Wormsley Library, Buckinghamshire. (Photo: Olivia Freuler) |

Several publishers and art dealers had pioneered the genre in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, notably the French art dealer Ambroise Vollard (1866–1939), who, in 1900, published Parallèlement by the French poet Paul Verlaine (1844-1896), with lithographs by the artist Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947). These set themselves apart from earlier pictorial illustrations because of the way in which they explored the broader mood and themes of the poems instead of focusing mainly on the actions or situations described in the text (Castleman, 1994, pp.27-28). Similarly, Hélène de Beauvoir’s engravings for La femme rompue the different emotional states of the main character through figures that are either enclosed in small boxes or caught in a chaotic spiral of jumbled, jagged lines, thus powerfully conveying the way in which the narrator’s life is torn apart and tipped upside down by sudden and unexpected revelations.

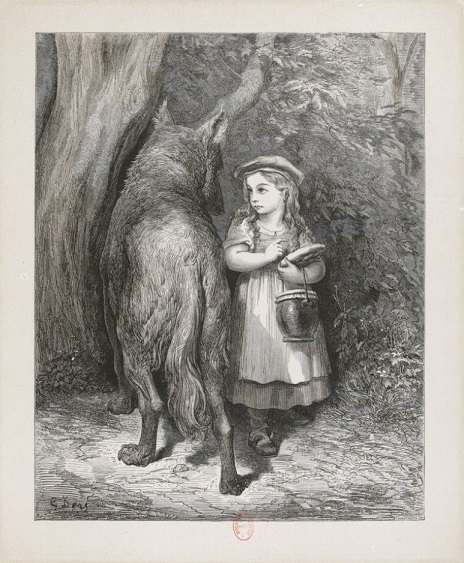

In her own memoirs, Hélène expressed a certain fondness for working in black and white and mentions her admiration for classic French tales by La Comtesse de Ségur (1799-1874) and Charles Perrault (1628-1703), who respectively authored Les Malheurs de Sophie (1858) and Histoire ou Contes du temps passé (1697), citing in particular the illustrations by Gustave Doré (1832-1883) for Perrault’s Contes as an early source of inspiration.

| Gustave Doré. Illustration for ‘Le Petit Chaperon Rouge’ in Perrault, C. 1862. Les contes de Perrault. Paris: J. Hetzel and Librairie Firmin Didot Freres et Fils. Woodcut. (Image: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France) |

Simone was supportive of her sister’s artistic career, and frequently helped pay for her studio in the rue Santeuil, Paris, in her formative years. However, her feelings about Hélène’s capabilities as an artist — and about women artists in general — were rather mixed, as is revealed through one of her letters to Sartre written in May 1954 (De Beauvoir, Sartre and Le Bon de Beauvoir, 1992, p.504) and in Le deuxième sexe, in a chapter titled “La Femme indépendante” where she laments the way in which women artists frequently see their work merely as a way to pass the time. (De Beauvoir and Parshley, 1953, pp.663-665). It wasn’t until 1966, on the occasion of the aforementioned speech in Japan, that Simone began to defend women artists and highlight the lack of support often faced by women who chose art as their vocation – a turning point that certainly encouraged a collaboration between the two siblings.

One hundred and forty-three copies were made of the illustrated edition of La femme rompue. Of the sixteen engravings produced by Hélène de Beauvoir for this publication, five form part of the Taylor Institution Library’s Strachan Collection of livres d’artistes extracts (now housed, for conservation reasons, at the Sackler Library). The collection was built by Walter Strachan (1903-1994) from the 1940s onwards and in it are a number of other works illustrated by women artists: Michèle Bardet, Micheline Catti (b.1926), Gisèle Celan-Lestrange (1927-1991), Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979), Denise Esteban (1924-1986), Léonor Fini (1908-1996), Carmen Martinez, Germaine Richier (1904-1959), Suzanne Roger (1898-1986), Brigitte Simon (1926-2009) and Ania Staritsky (1908-1981), all of whom are listed below along with the books’ authors.

| Ania Staritsky. Illustration from: Albert-Birot, P., 1978. Poèmes du dimanche. Paris: Editions sic. Etching. W.J. Strachan Collection, Taylor Institution Library, Oxford. (Image: Strachan, W. J., 1987. Le livre d’artiste) |

Olivia Freuler, Graduate Library Trainee, Sackler Library, Bodleian Libraries

Texts with illustrations by women artists in the Taylorian’s W.J. Strachan Collection

ALBERT-BIROT, P. (Author), STARITSKY, A. (Artist), 1978. Poèmes du dimanche. Paris: Editions sic.

BONNEFOY, Y. (Author), ESTEBAN, D. (Artist), 1973. Une peinture métaphysique. Paris: Esteban.

BUTOR, M. (Author), MARTNEZ, C. (Artist), 1976. Devises fantômes. Paris: Martinez.

CELAN, P. (Author), CELAN-LESTRANGE, G. (Artist), 1965. Atemkristall. Paris: R. Altmann.

CELAN, P. (Author), CELAN-LESTRANGE, G. (Artist), 1969. Schwarzmaut. Vaduz: Editions Brunidor.

DE NERVAL, G. (Author), FINI, L. (Artist), 1960. Aurélia. Monaco: Le Club International de Bibliophilie.

DORCELY, R. (Author), ROGER, S. (Artist), 1961. S.O.S. Paris: Galerie Louise Leiris.

ESTEBAN, C. (Author), SIMON, B. (Artist), 1968. La saison dévastée. Paris: D. Renard.

GARNUNG, F. (Editor), BARDET, M. (Artist), 1956. Epitaphes grecques et epitaphes funéraires grecques. Paris: Les Impénitents.

GHERASIM, L. (Author), CATTI, M. (Artist), 1967. Droit de regard sur les idées. M. Paris: Editions Brunidor & Robert Altmann.

RIMBAUD, J-A. (Author), RICHIER, G. (Artist), 1951. Une saison en enfer, Les déserts de l’amour, Les illuminations. Lausanne: Gonin.

SHAKESPEARE, W. (Author), FINI, L., (Artist), 1965. La Tempête. Paris : Aux dépens d’un amateur.

TZARA, T. (Author), DELAUNAY, S. (Artist), 1961. Juste présent. Paris: Galerie Louis Leiris.

ZDANEVICH, I. (Author), STARITSKY, A. (Artist), 1982. Un de la brigade. Paris: Hélène Iliazd.

I would like to thank Nick Hearn, French and Slavonic Subject Specialist, Taylor Institution Library, for his help in researching the Zdanevich title.

Bibliography

CASTLEMAN, R., 1994. A century of artist’s books. New York: Museum of Modern Art.

DE BEAUVOIR, H., ROUTIER, M. (ed.), 1987. Souvenirs. Paris: Séguier.

DE BEAUVOIR, S., 1959. Memoirs of a dutiful daughter. Translated by KIRKUP, J. New York and Cleveland: World Publishing Company. (Originally published in 1958, Mémoires d’une jeune fille rangée. Paris: Gallimard).

DE BEAUVOIR, S., 1953. The second sex. Translated by PARSHLEY, H.M. London: Jonathan Cape. (Originally published in 1949, Le deuxième sexe. Paris: Gallimard)

DE BEAUVOIR, S., 1969. The woman destroyed. Translated by O’BRIAN, P. London: Collins. (Originally published in 1967, La femme rompue: L’Age de discrétion. Monologue. Paris: Gallimard).

DE BEAUVOIR, S. 1979. La femme et la création. In: DE BEAUVOIR, S., FRANCIS, C. (ed.) and GONTIER, F. (ed.), Les écrits de Simone de Beauvoir: la vie, l’écriture, avec en appendice, textes inédits ou retrouvés. Paris: Gallimard.

DE BEAUVOIR, S., SARTRE, J-P., LE BON DE BEAUVOIR, S. (ed.), 1992. Letters to Sartre. Translated by HOARE, Q. London: Vintage. (Originally published in 1990, Lettres à Sartre. Paris: Gallimard).

MONTEIL, C., 2004. The Beauvoir sisters. Translated by DE JAGER, M. Emeryville, CA: Seal Press.

PERRAULT, C., STAHL, P.J. (ed.), DORE, G. (ill.) 1862. Les contes de Perrault. Paris: J. Hetzel and Librairie Firmin Didot Freres et Fils.

STRACHAN, W. J., 1987. Le livre d’artiste. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum and Taylor Institution.

WEBER-FEVE, S., 2010. (Re)Displaying Femininity and Home with Annie Ernaux and Simone De Beauvoir. In: WEBER-FEVE, S., Re-hybridizing transnational domesticity and femininity: women’s contemporary filmmaking and lifewriting in France, Algeria, and Tunisia. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Online

BEATTIE, S., 2015. The owls are not what they seem…. [Online] Victoria & Albert Museum. [Jun 1, 2017]. Available: http://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/factory-presents/the-owls-are-not-what-they-seem.

KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK. La femme rompue [Online] Koninklijke Bibliotheek. [20 April, 2017]. Available: https://www.kb.nl/en.

Further reading

JOHANKNECHT, S. et al., 2007. [Artist’s books: Special issue]. Art libraries journal, 32 (2).