The Image of Dante, the Divine Comedy and the Visual Arts

in the Ashmolean Museum and the Taylor Institution

II: The Divine Comedy Illustrated

This is the second of two short articles concerning the iconography of Dante as represented in the collections of the Ashmolean Museum and the Taylor Institution in Oxford. The first concerned the image of Dante himself. This one is focused on Ashmolean and Taylorian illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy.

It has often been said that the Divine Comedy is impossible to render in another medium – and that those who have tried to depict the Comedy have all, more-or-less hopelessly, failed. Some have been criticised for being too literal, failing to engage with the higher purpose of the poem; others for sacrificing Dante to their personal artistic ambitions. Underlying these criticisms is an idea of Dante’s text as a pure and independent work of art. Anything added to this is suspect. Such arguments are equally by-products of a misguided cult of authenticity, reinforced in this context by an enduring academic tendency to privilege the word over the image.

Rather than making a fetish of some imagined original and ideal reader of the poem, and consequently lamenting the supposed corruption of interpreters, it makes more sense historically to consider with an open mind the various ways in which the Comedy has been experienced across the seven centuries since its composition. Reception has always entailed visualisation – whether in the material frame of the text or in the mind of the reader. The reception history of the Comedy, seen through the material evidence of the book in its many editions, is a constant reminder of the ever-changing variety of Dante’s readers. In fact, the evidence of imagery associated with Dante, which can be sampled from the holdings of the Ashmolean Museum and the Taylor Institution Library, indicates what we know ourselves as readers: that text and visual images are constantly in mutual dialogue.

The Comedy began to be illustrated almost as soon as it was written down: the earliest manuscript copies containing pictures date from the second quarter of the fourteenth century. More than five hundred codices of the poem from this and the following century have some form of pictures, although half of these cases include only minimal imagery, while some 150 are extensively illustrated. The arrival of printing, therefore, did not inaugurate the illustrated Comedy. The Bodleian Library possesses important examples of this early manuscript tradition, whilst the illustrated texts in the Taylor Institution Library are printed versions from the late fifteenth century onwards.

Sandro Botticelli, Illustration to Inferno Canto XV, facsimile Zeichnungen von Sandro Botticelli zu Dantes Goettlicher Komoedie: nach den Originalen im K. Kupferstichkabinett zu Berlin (Berlin: G. Grote’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1887) Taylor Institution Library: REP.X.55 (plates)

Botticelli’s enormous project to illustrate the Comedy was, in a sense, the culmination of the medieval tradition of illustrated manuscript copies of the poem. Botticelli’s drawings themselves are now divided between Rome and (for the greater part) Berlin. The acquisition of these sheets in 1884 by the Kupferstichkabinett zu Berlin (Museum of Prints and Drawings) was followed by the publication of facsimiles of the complete series, made to the highest standards of the day and disseminated, as an act of cultural diplomacy, to the major collections of Europe. The Taylor Institution Library owns a copy of the portfolio of loose plates.

Botticelli’s patron must have been a wealthy Florentine patrician, who was content for his artist to work on a grand scale, and to allow his imagination, responding to the poem, to build creatively on the pre-existing repertoire of illustrations to the Comedy. The moment was an important one in the process of Tuscan re-adoption of the exiled Florentine: in 1481, a decade after the appearance of the first, north Italian, printed edition, the Comedy was published in the city of Dante’s birth. This version was accompanied by an extensive commentary and a patriotic introduction by Cristoforo Landino, who boasted that the new edition effectively repatriated the author: ‘…Firenze lungo tempo dolente ma finalmente lieta sommamente si congratula col suo poeta Dante nel fine di due secoli risuscitato et restituto nella patria sua’ (‘After a long period of grief, Florence can finally and happily celebrate to the utmost with her poet, Dante, who after two centuries has been restored to life and to his homeland’). The book was also illustrated with woodblock prints, which for the first half of Inferno were based on the drawings on which Botticelli was evidently simultaneously at work. For the rest, Botticelli’s progress was evidently too slow to be of use, and other designs were deployed. These woodblocks would be re-used in diverse editions over several years.

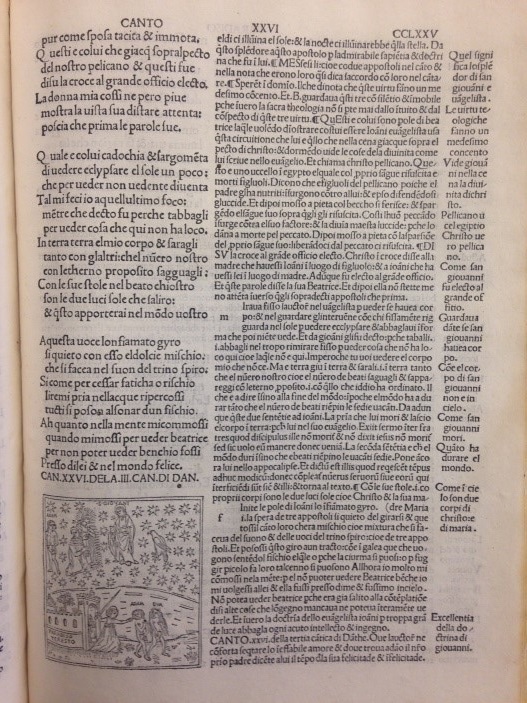

Commento di Christophoro Landino fiorentino sopra la comedia di Dante Alighieri poeta fiorentino (Venice, 1491) Taylor Institution Library: ARCH.Fol.It.1491(1)

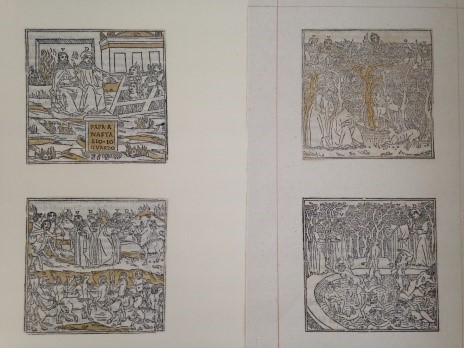

The Ashmolean Print Room possesses a number of detached woodcuts from this series, painstakingly cut out from copies of the book by early collectors of printed images. In some cases, previous owners of the books had enhanced the pictures with the addition of colour.

Woodcuts from the Comedy published in Venice in 1491(?) Ashmolean Museum: Douce Collection WA.2003 (Italian sequence, unmounted)

Landino’s extensive commentary made a visual announcement that the text was quasi-biblical in its need of authoritative exposition. By the same token, however, the annotations threatened to overwhelm the text, which, like the Bible, was also known in less intellectualised forms. In an evident reaction against the perceived clutter of the Tuscan layout, the great Venetian publisher Aldus Manutius produced a simple text edition, with the collaboration of Pietro Bembo. The latter owned a copy of the Comedy once given by Boccaccio to Petrarch, which encouraged the editors to think their version superior to others. Their claim was that modern Tuscan versions had corrupted the text with changes in vernacular usage, whereas they were presenting the ‘authentic’ Dante. Once again, an idea of authenticity is contrasted with the supposed inadequacy of anything which might betray the process of reception and the passage of time. Aldus’s end-note authoritatively declares: ‘Venetiis in aedibus Aldi accuratissime men’. The title page bears the simple legend: ‘Le terze rime di Dante’. The text appears unencumbered.

Lo’nferno e’l Purgatorio e’l Paradiso di Dante Alaghieri (Venice: Aldus Manutius, 1502) Taylor Institution Library: ARCH.12°.It.1502

But although the prestige of the Bembo-Aldus text meant that it was frequently copied thereafter, it was in fact far from perfect, giving the opportunity for the Tuscan Alessandro Vellutello to condemn its failings and so to reclaim the book for Florence. Vellutello’s extra-annotated edition of 1544 (ironically published in Venice) would in turn provide the initial basis for the official Florentine imprint of the Accademia della Crusca in the 1590s. The 1544 printing also introduced a number of diagrams of Hell, based partly on the work on this subject written in Florence in the fifteenth century by Antonio Manetti. Sixteenth-century readers were interested to apply the latest techniques of geographical measurement to their reading of the poem. It is often pointed out that many more editions of Petrarch than of Dante appeared in print before 1600; yet the latter was not seen as outdated.

La comedia di Dante Aligieri con la noua espositione di Alessandro Vellutello (Venice, 1544) Taylor Institution Library: ARCH.8°.It.1544(2)

In 1564, for the first time, the author appeared on the title page both in the largest lettering and in a portrait (apparently derived from those by Raphael, or otherwise from those fifteenth-century Florentine depictions on which Raphael himself had drawn).

Dante con l’espositione di Christoforo Landino et di Alessandro Vellutello sopra la sua comedia dell’Inferno, del Purgatorio, & del Paradiso (Venice, 1564)

Taylor Institution Library: ARCH.Fol.It.1564(1)

The Ashmolean Museum possesses an extraordinary testament to the status of Dante in mid-sixteenth-century Tuscany, in the form of a wax relief, probably made in the late eighteenth century as a cast copy of its Renaissance original. That work was made by the young virtuoso sculptor Pierino da Vinci, on commission from the prominent Dante scholar, engineer, and Medicean governor of Pisa, Luca Martini. The subject is the shocking scene, described in Cantos 32 and 33 of Inferno, of the imprisonment and starvation by Archbishop Ruggiero of Pisa of his enemy, Ugolino, together with the latter’s sons and grandsons. Both the patron’s deep knowledge of the poem and his official posting to Pisa explain the appearance of this, the first Dantean subject to be rendered as an independent work of art.

Pierino da Vinci (after), Ugolino and His Sons and Grandsons in the Tower of Famine. Wax relief. Probably late 18th-century Ashmolean Museum: WA1897.190 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Only months before this commission, in the late 1540s, a famous discussion had been conducted in Florence concerning the status of the various arts. Benedetto Varchi, who orchestrated that debate together with Luca Martini, proposed that in order to render Dante’s Inferno or Pugatorio in visual art, the better medium would be, not painting, but relief sculpture. Giorgio Vasari, who saw the relief which ensued, commented that ‘In this work Vinci displayed the excellence of design no less than did Dante the perfection of poetry in his verses, for no less compassion is stirred by the attitudes shaped in wax by the sculptor in him who beholds them, than is roused in him who listens to the words and accents imprinted on the living page by the poet.’ Bearing in mind this reference to a wax version, it is not altogether impossible, on the available evidence, that the Ashmolean relief was made by Pierino da Vinci – even if the arrival of the bronze in Britain creates a plausible context for the manufacture of a wax version (together with several terracotta casts which are known, and of which the Ashmolean possesses an example: WA1888.CDEF.S28) for an eighteenth-century collector. (The bronze version, which for more than two centuries resided in the house of the Dukes of Devonshire at Chatsworth, was in 2010 sold to the Prince of Liechtenstein; it is now in that family’s palace in Vienna.)

The afterlife of Pierino da Vinci’s bronze Ugolino had momentous consequences for the imagery of the Comedy in the nineteenth century. By the seventeenth century it had been attributed to Michelangelo: not a foolish idea, given Pierino’s admiration and emulation of the master which is so evident in the figures. Acquired and brought home by a travelling English artist around 1700, it was seen by the painter and critic Jonathan Richardson, who in an influential essay on art criticism praised the sculptor’s ability to lift the communication of great ideas even beyond the power of words.

Joshua Reynolds, himself a passionate admirer of Michelangelo, responded to Richardson’s challenge with a painting of the same subject, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1773 (now at Knole, Kent). Once John Dixon had in 1774 made an engraving after Reynolds’s picture, the tragic subject was launched as an ideal point of reference for the Romantic imagination, as Dante’s poem came back into favour around 1800. Along with the episode of Paolo and Francesca, that of Ugolino’s imprisonment dominated the selection of scenes from the Comedy chosen for depiction by numerous nineteenth-century artists.

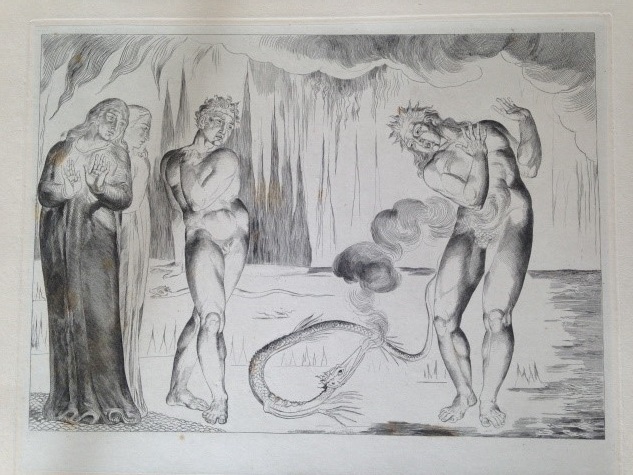

At the same period a number of artists rose to the challenge of illustrating the entire poem. By the time that Gustave Doré embarked on his Dante series in the 1850s, the poet was thoroughly established in French and European culture, which helps to explain the enormous impact of those particular designs. It was, by contrast, at a relatively early moment in the nineteenth-century boom in Dante’s critical fortune that William Blake, in the 1820s, undertook a similar project. Blake’s response to Dante was so personal, that it has often been assumed to have sacrificed the poem to Blake’s idiosyncratic visual mythologies. This does injustice to the work, on which Blake was exclusively and passionately engaged in the final, illness-ridden years of his life. Blake had enormous respect for Dante, despite disagreeing with aspects of his theology; but the strength of his imagery stems from the fact that he regarded himself as equal to the medieval poet as both poet and visionary. A century ago Blake’s watercolour drawings, which he made as steps towards a never completed series of engravings, were distributed to various museums by the Art Fund. One given to the Ashmolean is amongst the most beautiful of the set. It relates to Paradiso Canto 24, and represents Dante and Beatrice in the Constellation of Gemini.

William Blake, Beatrice and Dante in Gemini, 1824-7. Watercolour over graphite with some pen and ink and black chalk Ashmolean Museum: WA1918.5 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

The Print Room also holds a set of the seven partially completed prints by Blake, which his friend and publisher John Linnell had solicited from him.

William Blake, The Six-footed Serpent Attacking Buoso de’ Donati (Inferno Canto 25). Engraving Ashmolean Museum: WA1941.27.5

In the next generation and in his own fashion, Dante Gabriel Rossetti also brought into focus aspects of the Comedy which had previously been less noticed. He contributed to a new fascination with the youthful Dante of the lyric poetry and the Vita Nuova. The poet, in Rossetti’s imagery, shifts from the role of hero to that of lover. This is exemplified in the Ashmolean’s Beatrice at a Marriage Feast Denying Her Salutation to Dante.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Beatrice at a Marriage Feast Denying Her Salutation to Dante. Watercolour and bodycolour with some pen Ashmolean Museum: WA1942.156 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Rossetti was prompted in particular directions by John Ruskin, who proposed several subjects for the artist to take from Purgatorio. One of these was the character of Matelda (or Matilda), seen by Dante in the Earthly Paradise. Rossetti’s painting of this subject is lost, but the Ashmolean holds a detailed preparatory drawing.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Dante’s Vision of Matilda Gathering Flowers (Purgatorio Canto 28). Pen and brown ink. Ashmolean Museum: WA1942.157 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Dante describes Matelda as ‘una donna soletta’ who picks flowers and sings by herself. Rossetti, ever drawn to ideas of friendship and evidently eager, perhaps under the influence of Ruskin, to emphasise a feminine principle, multiplied the female presence in his image.

Other artists in Oxford collections have engaged in diverse ways with Dante’s Comedy. Rodin’s work for his never completed Dantesque scheme, The Gates of Hell, is represented in the Ashmolean Print Room by a small engraving of Souls in Purgatory (WA1946.263). A few drawings for Tom Phillips’s Inferno (1985; WA2009.94 and WA2009.96–99) are held in the Print Room, while several boxes of related materials are catalogued in the Bodleian Library Special Collections. Also in the Print Room are sets of Geoff MacEwan’s Inferno (1990) and Purgatory (2008) engravings. In the latter the Earthly Paradise, an oasis of green ringed by purificatory flames, bursts into colour and into an abstract simplification of form. The poem continues to find imaginative responses which themselves generate new readings and new readers.

Note:

In June 2017 seminars on Dante and the visual arts were held, on two occasions for different audiences, in the Western Art Print Room of the Ashmolean Museum. The project was the result of my experience as Faculty Fellow in the Department of Western Art at the Ashmolean. I am very grateful to the following who contributed generously and enthusiastically to the collaboration: the Keeper of Western Art, Dr Catherine Whistler; the Leverhulme Research Assistant (Raphael Project), Angelamaria Aceto; the Print Room Supervisors, Dr Caroline Palmer and Katherine Wodehouse; the Bodleian Libraries’ Librarian for Art & Architecture, and for Italian Literature & Language, Clare Hills-Nova; the Picture Library Curator of the Ashmolean Museum, Amy Taylor; and Jim Harris, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Teaching Curator at the Ashmolean, together with Unity Coombes and Ben Skarratt, UEP Museum Assistants.

Professor Gervase Rosser

History of Art Department & Faculty of History

University of Oxford