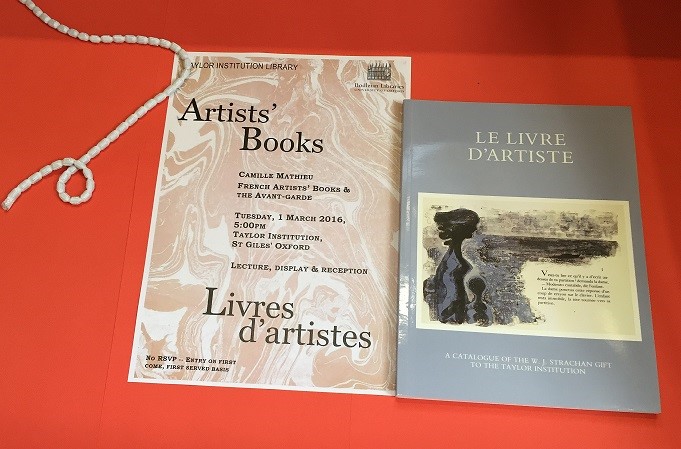

‘Listening to Dante: An Audio-Visual Afterlife’: Film – Readings – Vinyl – Books – Images

by David Bowe

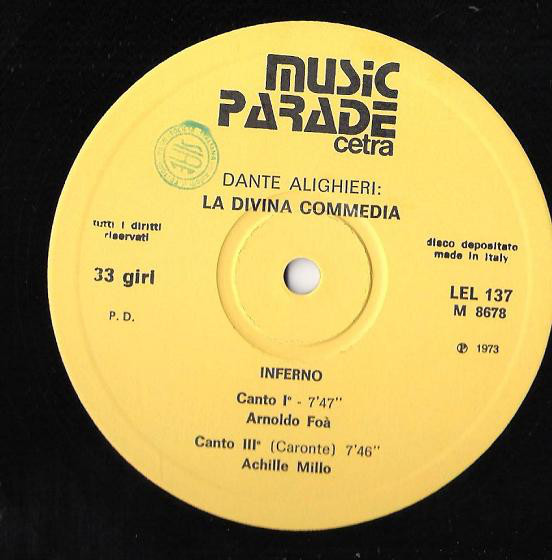

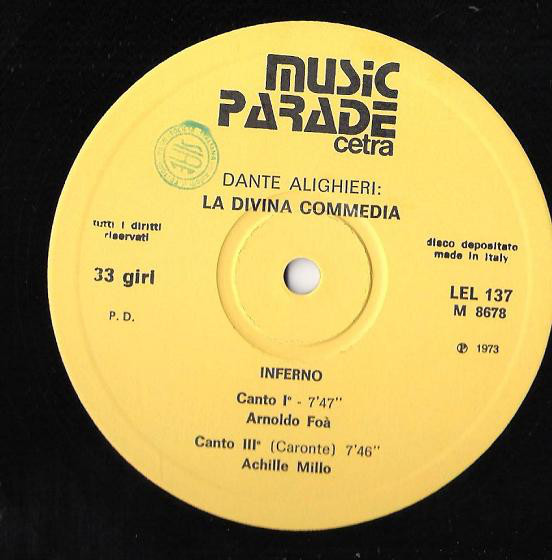

It all started with a box of LPs. Well, strictly speaking, it all started with the birth of Dante Alighieri in 1265 and his subsequent writing of the three-part epic poem the Divine Comedy (the Commedia to its friends) begun in 1308 and finished not long before his death in 1321. The LPs, a set of recordings pressed by CETRA in 1964, and featuring readings of the complete Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso by Arnoldo Foà, Carlo D’Angelo, Achille Millo, Giorgio Alber-tazzi, Antonio Crast, Romolo Valli and Tino Carraro, were placed on my library desk by the Taylorian’s Italian Literature and Language Librarian, together with a note saying, ‘I thought these might be of interest’. And they were, providing the meeting point of my love for Dante and for slightly old-fashioned recording technologies. The road this took me down was a little unexpected, as I was prompted to contemplate the range of responses that Dante’s writing has provoked over the centuries, from the earliest illuminators and commentators, to the most recent translations, adaptations, and research.

It all started with a box of LPs. Well, strictly speaking, it all started with the birth of Dante Alighieri in 1265 and his subsequent writing of the three-part epic poem the Divine Comedy (the Commedia to its friends) begun in 1308 and finished not long before his death in 1321. The LPs, a set of recordings pressed by CETRA in 1964, and featuring readings of the complete Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso by Arnoldo Foà, Carlo D’Angelo, Achille Millo, Giorgio Alber-tazzi, Antonio Crast, Romolo Valli and Tino Carraro, were placed on my library desk by the Taylorian’s Italian Literature and Language Librarian, together with a note saying, ‘I thought these might be of interest’. And they were, providing the meeting point of my love for Dante and for slightly old-fashioned recording technologies. The road this took me down was a little unexpected, as I was prompted to contemplate the range of responses that Dante’s writing has provoked over the centuries, from the earliest illuminators and commentators, to the most recent translations, adaptations, and research.

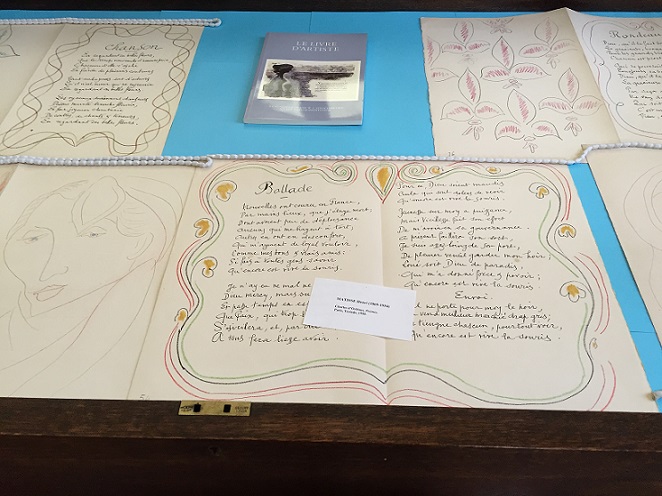

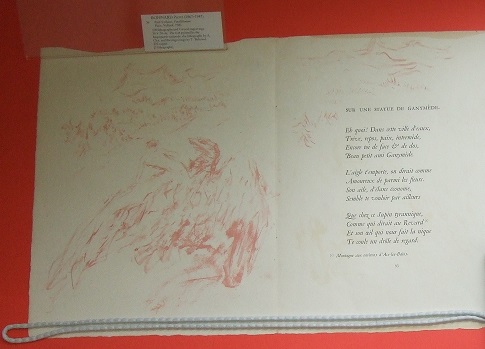

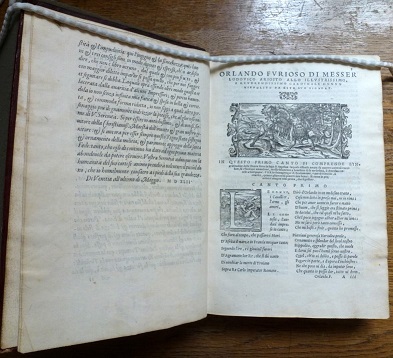

This led me to the Taylor’s collections of rare printed books, dating from the 15th to the 20th centuries, to films, operas, and symphonic poems from all across the world and on the internet, and thence to a Taylorian event at which these different media were considered.

For the Case List of Works on Display in the Voltaire Room and Vestibule, click here:

2016-05 DanteCaseList-Voltaire Room And Vestibule

In 1782 Britain saw the publication of the first full translation of Dante’s Inferno into English, by one Charles Rogers. The first English translation of the entire Divine Comedy, by the Irish cleric Henry Boyd, was published in 1802 (though his version of Inferno first appeared as early as 1785).

Thanks to the collecting of renowned Cardiff-born Dante Scholar Edward Moore (a fellow of The Queen’s College and later Principal of St Edmund Hall in Oxford), and courtesy of a long-term loan from The Queen’s College, the Taylor Institution Library holds copies of both of these translations. Moore was working towards the end of a 19th Century which saw the growth of both general readerly interest in the Florentine poet and the emergence of the formal discipline of Dante Studies in the Anglophone world.

Thanks to the collecting of renowned Cardiff-born Dante Scholar Edward Moore (a fellow of The Queen’s College and later Principal of St Edmund Hall in Oxford), and courtesy of a long-term loan from The Queen’s College, the Taylor Institution Library holds copies of both of these translations. Moore was working towards the end of a 19th Century which saw the growth of both general readerly interest in the Florentine poet and the emergence of the formal discipline of Dante Studies in the Anglophone world.

Moore founded the Oxford Dante Society in 1876 and the Dante Society of America was founded by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, and Charles Eliot Norton in 1881. These three had previously met as a less formal Dante Club while Longfellow prepared his famous translation of the Comedy, first published in 1867. Back in Oxford, our own Edward Moore was also responsible for the first modern edition of Dante’s works in Italian, the so-called ‘Oxford Dante’, printed by Oxford University Press in 1894. This edition of Dante’s medieval texts was a landmark for Dante scholarship worldwide and also had the honour of being OUP’s first publication entirely in a ‘modern’ foreign language..

Contributing to this developing context, the Pre-Raphaelites and poets like Alfred Lord Tennyson were discovering Dante’s stories, poetry, and the powerful visual imagery which emerged from his work. Few of the larger collections of pre-Raphaelite art, including that of are without images drawn from Dante. Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum (next door to the Taylorian) has a fine collection of Pre-Raphaelite works, recently re-installed, and includes Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s ‘Dante drawing an Angel on the First Anniversary of Beatrice’s Death’.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Dante drawing an Angel on the First Anniversary of Beatrice’s Death (Ashmolean Museum: Watercolour and bodycolour on paper, 1853)

The 19th century wasn’t the first time that echoes of Dante’s writing had been heard in England. The works of Chaucer are shot through with strands of allusion to and quotation or adaptation of Dante’s writing, especially the Comedy. For instance, the Wife of Bath borrows a few lines on the theme of nobility from Purgatorio Canto 7, and the Prioress’s invocations of the Virgin Mary are indebted to St. Bernard’s prayer at the start of the 33rd Canto of Paradiso. One of the most explicit acknowledgements of Dante as source text comes in the Monk’s Tale, however: the Monk tells the tragedye of one Hugelino and, having recounted the starvation of father and sons while imprisoned by Archbishop Ruggieri of Pisa, he directs curious listeners to read the Inferno (Dante’s telling of the episode is found in Canto 33).

Whoso wol here it in a lenger wise

Redeth the grete poete of Taille

That highte Dant, for he kan al devyse

Fro point to point; nat o word wol he faille.

[Whoever wants to hear it in a longer version

Read the great poet of Italy

Who is called Dante, for he can all narrate

In great detail; not one word will he lack.]

Geoffrey Chaucer, The Monk’s Tale, 2459-2462

This early foray of Dante into English was short-lived and we have to wait for Milton’s Paradise Lost for another sustained literary engagement with Dante’s works in English. This is not to say he was unknown in England during the intervening period, however. For example, thanks to the antiquarian meanderings of John Leland, we know that, in the 1530s, copies of a Latin translation and commentary of Dante’s Comedy were to be found in libraries in Oxford and in the Cathedral library of my home city of Wells. So Dante’s works were being translated into and read in the common intellectual language of Latin well before they made it into the English vernacular. Anyone interested in the fate of Dante’s works in the British Isles would do well to look at Nick Havely’s extensive work on the subject in his book Dante’s British Public, which offers an account of Dante’s readers and the fate of his texts in Britain from Chaucer to the modern day.

If translation was a part of the afterlife of Dante’s writing from a very early stage, one of the first indisputably ‘modern’ interpretations of Dante’s work emerged at the start of the 20th century in a relatively new medium, which would come to dominate the world of entertainment: the motion picture. 1911 saw the first (and possibly still the best) film adaptation of Dante’s Inferno. More interpretations would follow in 1924 & 1935 and there has been a recent flurry of animated films, an adaptation of Dan Brown’s ‘Dante-inspired’ Inferno, and there were reports last year that Warner Brothers were gearing up to make a new film in which Dante descends through the circles of Hell to save the woman he loves… There is something rather alarming about the fact that a 21st century entertainment company seems to struggle more than a 13th century poet with the idea of Beatrice as the one doing the saving, but it remains remarkable that so many feet of celluloid (and megabytes of digital film) continue to be devoted to this medieval poem. The 1911 Milano Films’ Inferno, sometimes (falsely) advertised as the Divina Comedia, is the oldest surviving feature-length film in existence and was arguably the first international blockbuster, taking in excess of $2million in the US alone. We have a sense of some audience reactions, including Nancy Mitford’s, who described seeing it in 1922 in a letter home from Italy:

‘most bloodthirsty and exciting … a man’s hands chopped off very close and full of detail, and a man dying of starvation and eating another man very very close to … helped to add excitement to a film full of battles … , molten lead, a burning city and other little every day matters.’

And one of the episodes being described by Nancy Mitford is the case of Ugolino and Ruggieri, which so inspired Chaucer’s Monk’s Tale. (You can find the full film here, on YouTube.)

The imagery used for Dante’s hell in this film isn’t itself entirely original. The directors’ scenography drew heavily from Gustave Doré’s iconic 19th century illustrations of the Divine Comedy. There’s something very striking about those engravings brought vividly to life on film and with special effects which were cutting edge at the time and can still sometimes startle (particularly in the more gruesome torments of lower hell that so captured Nancy Mitford’s admiration). The 1911 Inferno acts as a double adaptation, then, of text into image and illustration into moving picture.

The Doré connection is proof enough (and plenty more is available) that the appeal of Dante (and his creations) beyond Italy wasn’t limited to Britain, or the anglophone world. Liszt’s 1849 Après une Lecture du Dante: Fantasia quasi Sonata is more commonly know as the Dante Sonata, inspired by the Hungarian composer’s reading of the Italian poet’s Divine Comedy. (Connect here to Vitaly Pisarenko’s rendition.) Dorè and Liszt are but two representatives of the rich traditions of translation, reception and artistic response to his work across Europe and Russia, where Tchaikovsky penned a symphonic poem called Francesca da Rimini in 1876, and Rachmaninov was inspired to write an opera of the same name, based on the events of Inferno 5. Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov were not alone in seeing the musical potential for Francesca’s story, although, of a dozen operas named after Dante’s anti-heroine, only his and Riccardo Zandonai’s remain in the repertoire. Perhaps it is unsurprising that Francesca should be so enthusiastically adopted as a tragic operatic heroine. She is lyrical, enamoured, articulate, and doomed. Her adulterous (incestuous, by medieval standards) affair with her brother-in-law and the murderous wrath of her husband (who will, according to Francesca, end up in Caïna, the zone named for the biblical fratricide Cain and reserved for those who betray, often violently, their kin), are all features that beg for melodrama. Rachmaninov’s opera — available here — opens with a slow build towards the infernal storm — the ‘bufera infernal’ — of Inferno 5, which eternally buffets the souls of the carnal sinners. The score drives the action and reflects this atmosphere. We then see Dante enquiring about the souls and calling to Paolo and Francesca, who identify themselves and utter the immortal lines: “‘There is no greater sorrow / than to recall our time of joy / in wretchedness’” — “‘Nessun maggior dolore / che ricordarsi del tempo felice / ne la miseria’”.

Rachmaniov’s swirling, disorienting score gives a vivid sense of the frightening, overwhelming moment of Dante’s entry into Hell-proper, which the poet had previously characterised as a space full of ‘Diverse lingue, orribili favelle, / parole di dolore, accenti d’ira, / voci alte e fioche’ [Unfamiliar tongues, horrendous accents, / words of suffering, cries of rage, voices / loud and faint]. All these, Dante, recounts in Inferno III, ‘facevano un tumulto, il qual s’aggira / sempre in quell’ aura sanza tempo tinta, / come la rena quando turbo spira’ [made a tumult, always whirling / in that black and timeless air, / as sand is swirled in a whirlwind]. The vibrant and violent soundscape evoked by Dante’s poetry lends itself readily to musical and sonic responses, the text of his Divine Comedy often demands that we hear as we read, that we allow ourselves to be drawn into a synaesthetic muddling of sight and sound, just as Dante finds his own senses confounded on the 1st terrace of Purgatory.

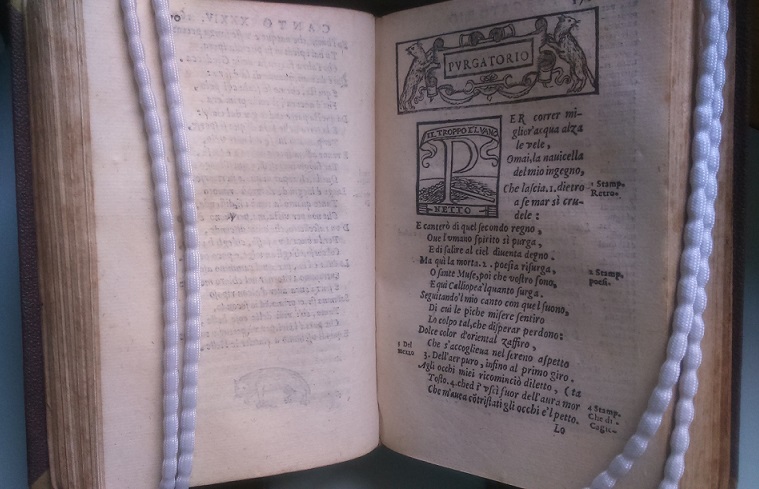

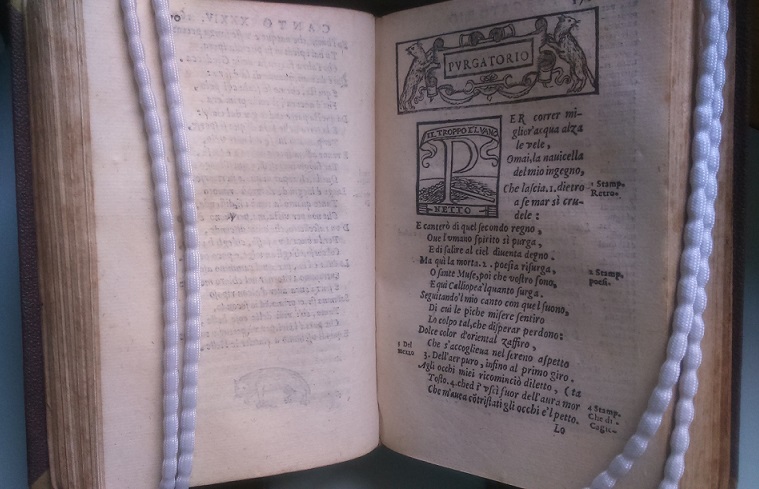

La Divina commedia: ridotta a miglior lezione dagli Accademici della Crusca (Firenze: Domenico Manzani, 1595)

After emerging from the Inferno, the next leg of Dante’s journey will be to ascend the mountain of Purgatory where penitent sinners undergo productive torments to pay for their sins and cleanse their souls in preparation for Heaven:

e canterò di quel secondo regno

dove l’umano spirito si purga

e di salire al ciel diventa degno.

[Now I shall sing the second kingdom

there where the soul of man is cleansed

made worthy to ascend to Heaven.]

Purgatorio I, 4-6

After a certain amount of milling about on the shores of Purgatory meeting those souls who left their repentance to the last minute, Dante passes through the gate leading to the Mountain where the real work of purgation takes place. The mountain is divided into terraces, each of which is dedicated to the purifying of a particular deadly sinful impulse: Pride, Envy, Wrath, Sloth, Avarice, Gluttony, and finally Lust. The first of these sins is corrected on the first terrace of the mountain of Purgatory and, as Dante emerges onto it, he is faced with three reliefs carved into the living rock. These reliefs depict three scenes of humility, the Virgin Mary accepting the will of God, King David dancing before Ark of the Covenant, and the Emperor Trajan taking time out of his busy schedule to grant justice to a widow whose son had been slain. And these freezes are not the work of man, but the art of God himself, surpassing all other art. Dante describes his sensory confusion in an act of divine ekphrasis: his eyes tell him that he can hear Mary speaking, but his ears tell him no, he can visually smell the incense burning in the scene of the dancing David, even though his nostrils are sure there is nothing to be smelled. Dante is faced with the art of the divine, which is impossible for human sense to fully comprehend or communicate, but Dante gives it a shot… His audacity leads to some beautiful verse and, subsequently, to a vibrant artistic tradition, as generations of artists took Dante’s text as a challenge to produce their own art of the divine. One of the most notable efforts comes from the pen of Botticelli, subject of a recent exhibition at the Courtauld Galleries (London).

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Though Botticelli’s illustrative programme for the Comedy is largely unfinished, the incompleteness takes on a poetic justice in the case of this particular canto, where God’s art is described as so beyond the realm of human hand. Indeed, Dante describes the angel Gabriel who, in this relief,

dinanzi a noi pareva sì verace

quivi intagliato in un atto soave

che non sembiava imagine che tace.

Giurato si saria ch’el dicesse ‘Ave!’

[appeared before us so vividly engraved

in gracious attitude

it did not seem an image, carved and silent.

One would have sworn he was saying ‘Ave,’]

(Purgatorio X 37-40)

Having now looked at Purgatorio, and, while any discussion of the audio-visual afterlives of the Comedy somewhat inevitably skews towards Inferno, given the comparative weight of artistic responses, translations, and adaptations of the first part of the poem, it would be remiss not to account at least briefly, for Paradiso, a realm which, even more than the divine art of Purgatory, defies representation. Even as Dante recounts the marvels he has seen, he accounts for the failure of language to express that which he has undergone. When recalling his final mystical vision in the heights of Paradiso 33, Dante tell us:

Omai sarà più corta mia favella

pur a quel ch’io ricordo, che d’un fante

che bagni ancor la lingua a la mammella.

[Now my words will come far short

of what I still remember, like a babe’s

who at his mother’s breast still wets his tongue.]

Paradiso XXXIII, 106-8

And again:

Oh quanto è corto il dire e come fioco

al mio concetto! e questo, a quel ch’i’ vidi

è tanto, che non basta a dicer ‘poco’.

[Oh how scant is speech, too weak to frame my thoughts.

Compared to what I still recall my words are faint —

to call them ‘little’ is to praise them much.]

Par XXXIII, 121-3

Of course, as with that divine art in the previous realm, this didn’t stop Dante exploring the possibility of representation in words, nor did it deter artists from endeavouring to depict the undepictable, Boccaccio again gives it his best shot, here illustrating Dante receiving a lesson on angelology from Beatrice in canto 28 of the Paradiso.

One artist who did eventually embrace the inexpressibility of Paradise, was Liszt, in another Dantean composition, A Symphony to Dante’s Divine Comedy. He had intended to compose a choral third movement to give voice to Paradiso, but was persuaded to shy away from any attempt to express the rapturous heights of heaven in his music, instead concluding his symphonic poem (as it is more often been classified), with a Magnificat.

Artists and entertainers, readers and scholars have listened to Dante in a variety of ways over the seven and half centuries since his death: interpretations, translations, appropriations, distortions, and homages ranging from the OUP’s Very Short Introduction, to Electronic Art’s very questionable videogame, from Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s sketches, to Mary Jo Bang’s thematically modernising translation. The Russian poet and essayist Osip Mandelstam, in the Conversations on Dante dictated to his wife in the mid 1930s, said, ‘It is unthinkable to read the cantos of Dante without aiming them in the direction of the present day. They are missiles for capturing the future.’ Our continued fascination with Dante’s poetry, the scores, and texts, and images that have been and continue to be generated and regenerated from those earliest illuminators, commentators, and biographers, to today’s artists, translators, filmmakers and writers demonstrate the continued resonance of his work and the lasting impacts of those missiles from the past. Dante has plenty more to tell us, if we continue to listen.

David Bowe, Victoria Maltby Junior Research Fellow, Somerville College

Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages

Further reading

Dante Alighieri. Inferno, translated by Mary Jo Bang (Minneapolis: Greywolf Press, 2012)

Peter Hainsworth & David Robey. Dante: a very short introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015)

N.R. Havely. Dante’s British public: readers and texts, from the fourteenth century to the present (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014)

Tristan Kay, Martin McLaughlin, and Michelangelo Zaccarello. ‘Introduction’, in Dante in Oxford: the Paget Toynbee Lectures, ed. by Tristan Kay, Martin McLaughlin, and Michelangelo Zaccarello (London: Legenda, 2011), pp. 1-23 (1)

Dagmar Korbacher, ed. Botticelli and the treasures from the Hamilton collection (London: Paul Holberton, 2016)

Osip Mandelstam. ‘Conversation on Dante’, in The Selected Poems of Osip Mandelstam, translated by Clarence Brown and W.S. Merwin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973)

Matthew Pearl. The Dante Club (London: Vintage, 2014)

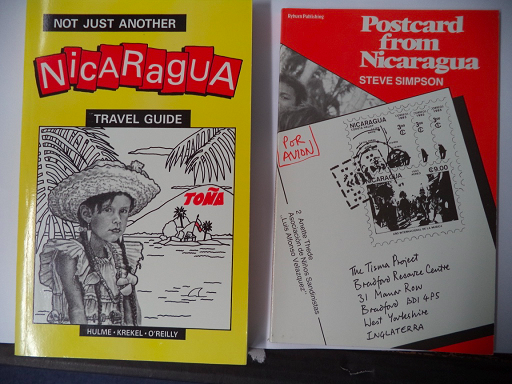

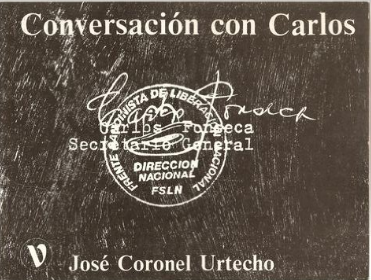

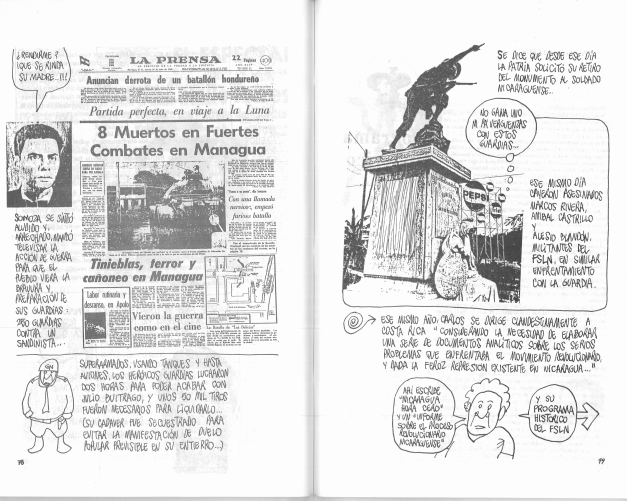

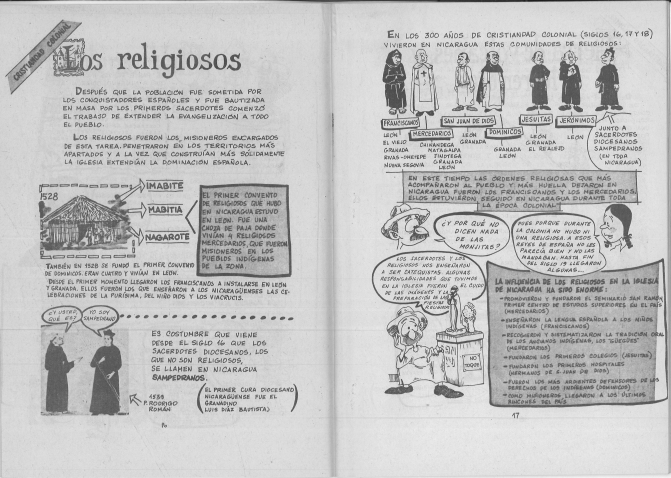

Readers may know him as the author of the very popular book Marx For Beginners which started the For Beginners series. Employing his characteristic style and satire he gives a short and simple narrative of Nicaragua from 1936, the year in which the Nicaraguan teacher and librarian Carlos Fonseca, founder of the FSLN, was born. The book tells Fonseca’s story with help of comic-book illustrations, photographs, and articles in an anarchic and accessible style.

Readers may know him as the author of the very popular book Marx For Beginners which started the For Beginners series. Employing his characteristic style and satire he gives a short and simple narrative of Nicaragua from 1936, the year in which the Nicaraguan teacher and librarian Carlos Fonseca, founder of the FSLN, was born. The book tells Fonseca’s story with help of comic-book illustrations, photographs, and articles in an anarchic and accessible style.

![ORLANDO / FVRIOSO / DI M. / LODOVICO ARIOSTO / Nuouamente / adornato di Figure di Rame / da Girolamo Porro […], Venice, Francesco de Franceschi Senese, 1584](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/taylorian/wp-content/uploads/sites/155/2016/08/2016-08-bbb-Francheschi1584-Resized.jpg)

![CIRIFFO CALVANEO / DI LVCA PVLCI / Gentilhuomo Fiorentino. / Con la Giostra del Magnifico Lorenzo / DE MEDICI […], Florence, Stamperia de’ Giunti, 1572](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/taylorian/wp-content/uploads/sites/155/2016/08/2016-08-CiriffoCalvaneo1572-Resized.jpg)

![DISCORSO / SOPRA IL PRINCIPIO / DI TVTTI I CANTI / D’ORLANDO FVRIOSO. / DELLA S. LAVRA TERRACINA, / detta nell’Academia de gl’incogniti, Febea […], Venice, Gabriel Giolito de’ Ferrari, 1565](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/taylorian/wp-content/uploads/sites/155/2016/08/2016-08-LauraTerracina1565-Resized.jpg)