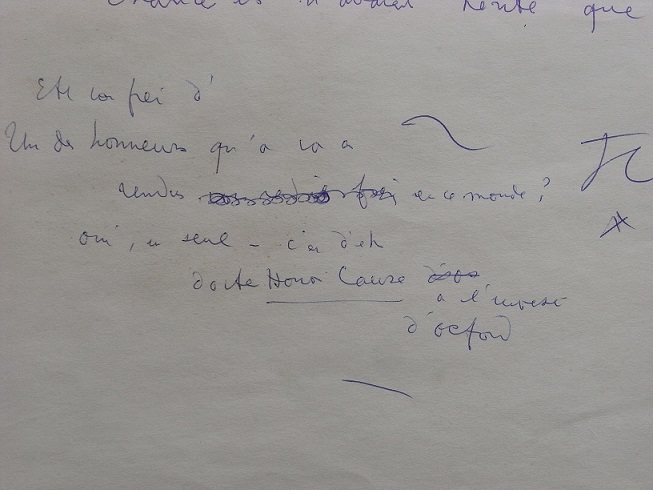

When Giles Barber retired from his post as Taylor Librarian in 1996, he moved with his wife Lisa to Charlbury and they shortly also acquired a holiday house in the far south-west of France, in the département of the Ariège. La Mandro, in the commune of Lescure, very soon became their main residence, and they immersed themselves in local life, became involved in a whole variety of activities – and they collected books. Their large collection of books on the Ariège and nearby areas of France has now been donated to the Bodleian by Lisa Barber, who writes:

We loved this area of France and anything published about the Ariège was of interest: its geographical situation in the central Pyrenees bordering Catalonia, life in the past in this region, the architecture of its many old churches, travellers’ descriptions, the painters who had worked in the region, and works both by and about its writers.

Included in this collection are a number of books on and in Occitan, and in particular on the Gascon language, spoken in Lescure in former days and still by a few of the older generation. In the collection one can find the three studies by Jean-Pierre Laurent (2002) (by profession an anaesthetist) on the dialects of Massat, the Séronais, and Aulus.

His information was carefully collected over many years from local people of an older generation (This and all further references are to be found in the bibliography at the end of this blog). Christian Duthil (2009) wrote on the language of the Ariège, while the dialect of Toulouse is studied by Jean Séguy (1978). Place-names of the area can be explicated by reference to two books by Bénédicte and Jean-Jacques Fénié (1992, 1997).

Abbé Grégoire, Rapport sur la nécessité et les moyens d’anéantir les patois et d’universaliser l’usage de la langue française. 1794 (Reprinted 1995)

Modern interest in these languages aims to preserve them but of great consequence was the effort to suppress them and the collection includes a reprint of a 1794 work by the Abbé Grégoire (1995) on the necessity of suppressing the dialect and ensuring that French became the standard language of communication. The Abbé’s efforts were not entirely successful and the anthologies of Gascon literature and folklore by Gaston Guillaume (1941) and Joan-Francés Bladèr (1966) contain some of the literary texts composed in the languages of the region.

There is also a fairly rare first edition of Belina, poema de tres cantas by Miqueu Camelat (1962).

- Miqueu Camelat Belina, poema de tres cantas, Sorgas – Institut d’estudis occitans, 1962

- Miqueu Camelat Belina, poema de tres cantas, Sorgas – Institut d’estudis occitans, 1962

Local history was one of our prime interests and our collection includes studies (of varying academic levels) of many small communes of the Ariège as well as of the larger and better-known towns. Paul Pédoya collected together all his own memories and that of others of his village of Montseron (2005), while Georges Olive wrote up the traditions of one area of the town of Saint-Girons: the Baléjou (1993). Christiane Miramont studied and wrote about the mills along the Lens valley (2005), the glass-blowers of the Volvestre (2003), and the somewhat turbulent life of Bruno de Ruade (1999).

Saint-Girons-les-Eaux (Ariège) : sources thermales Audinac; grande source chaude. Saint-Girons: 1948

Saint-Girons is the nearest town to Lescure and Giles himself wrote a book (2004), which maps out much of the history of the town through a study of its street-names. These range from the medieval Rue du Bourg to streets named after heroes and heroines of the Resistance. We picked up many other books about Saint-Girons, including the optimistic Saint-Girons-les-Eaux (1948), the record of a doomed attempt to turn Saint-Girons into a spa town. The hopes for this scheme were based on an idea to reroute the natural mineral waters of nearby Audinac which had been studied by Michel Dubuc in his work of 1882, of which we found a 1997 re-edition. An abandoned incomplete building at the end of a side street in Saint-Girons bears witness to the disappointed hopes of the promoters of the scheme.

Picture of the rotunda in Saint-Girons in Giles Barber’s book: Giles Barber Les Rues de Saint-Girons: les noms des rues et des édifices de la ville à travers les âges, leurs origines, ainsi que ceux des quartiers, hameaux et lieux-dits avoisinants 2004

A photo of this building, a rotunda, appears in Giles’s book along with an account of the failed project.

Saint-Lizier, next-door to Saint-Girons, boasts two cathedrals, one now a museum that was the see from the Middle Ages until the Revolution, and the present one, a beautiful medieval former parish church with wall-paintings and a lovely cloister. The collection includes a number of works on Saint-Lizier and one might pick out two more unusual books: the account by Pierre Assémat (a lawyer of Pamiers) of the confraternity, membership of which was obtained by going on pilgrimage to Compostella (2007) and Ortet’s history (2004) of how the Palais des Évêques of Saint-Lizier was turned in the nineteenth century into an “asile d’aliénés” (in modern parlance a psychiatric hospital but more akin to the English “lunatic asylum”).

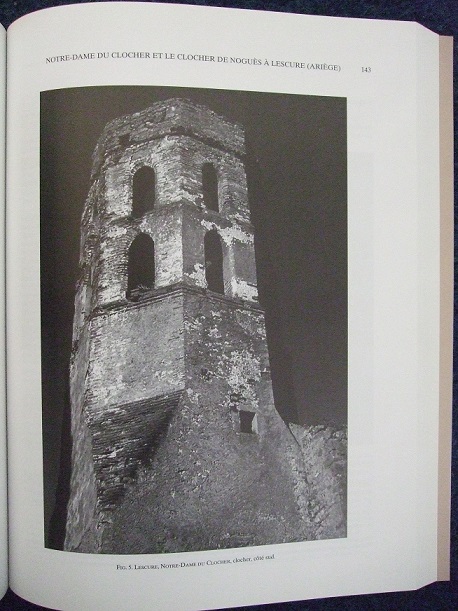

Photograph of the bell-tower of Noguès in Lescure from Lisa Barber’s ‘Notre Dame du Clocher et le Clocher de Noguès à Lescure (Ariège)’, Mémoires de la Société archéologique du Midi de la France, LXVII (2007), 135-44

About our own commune of Lescure we acquired from Richard de Meritens de Villeneuve, the author, the collected biographies of all those escurois who fought in the First World War (2006). Looking further back into the history of Lescure, I researched and wrote up the history of a church in Lescure (2007) and an offprint of this is included in the collections (as are others of my researches into medieval funeral slabs in the area).

Another English inhabitant of the Ariège, Scott Goodall, has been instrumental in setting up the commemorative annual four-day climb up and over the Pyrenees into Spain, in honour and remembrance of those who escaped that way from German and Vichy France during the Second World War, and both the English and the French versions of his book about this have joined the collection (2005).

Saint-Lizier, Saint-Girons, and Lescure are all in the western area of the Ariège called the Couserans, quite distinct from the eastern part which was the Comté de Foix, the difference felt by all local people and visible in such works here as J. de Lahondès (2001). Foix is still the préfecture (the rough equivalent of the county town) and houses the departmental archives, fully and competently described and listed by the current archivist, Claudine Pailhès, in her guide to the archives of Ariège published in1989. She has used these archives and other sources to write and publish a number of excellent books on the region (see bibliography below).

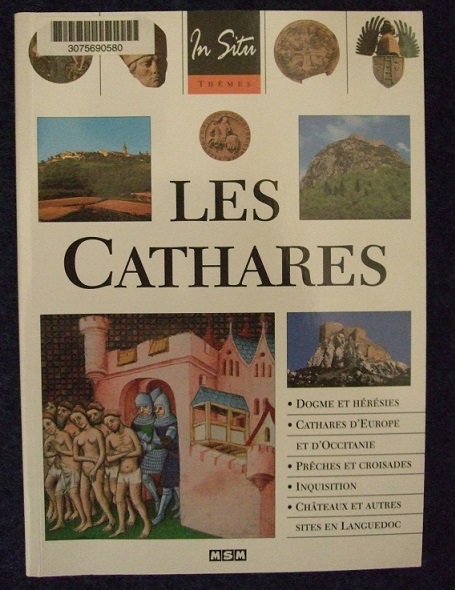

In this eastern area of the Ariège are found the Cathar sites of Montaillou and Montségur and one cannot live long in the area without hearing about these medieval heretics and the Albigensian crusade. Nowadays the places and buildings associated with them have been turned into tourist attractions. As much nonsense as good scholarship has been written about them. Our collection contains several books on the Cathars and also the careful study of the other side of the picture edited by Laurent Albaret (2001).

- Les Inquisiteurs : Portraits de défenseurs de la foi en Languedoc (XIIIe – XIVe siècles), (edited by Laurent Albaret Toulouse : Privat, 2001

- Les Cathares Vic-en-Bigorre Cedex : MSM, 2000. (One of the books in the Ariège collection about the Cathars

- Copy of Chronique sur Rennes-le-Château : Marie d’Etienne, le trésor oublié (1998)by Germain Blanc-Delmas, dedicated to Lisa and Giles Barber by the author

Another book to look at an unusual side to matters is the often hilarious account (1998) by Germain Blanc-Delmas of his childhood in Rennes-le-Château, where his father was Mayor. Long before either the Da Vinci Code or the Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, stories woven around the abbé Bérenger Saunière and his imagined discovery of a treasure beneath the stones of the present village led to incursions of illicit treasure seekers, who would hire a holiday house for a season and proceed to dig up the floors and tunnel out from there.Blanc-Delmas with a group of other young lads happily sabotaged these efforts and devised tricks and frights for the night-time diggers, while his father battled to stop the streets of the village from collapsing due to the subsidence caused by the tunnels.

Catherine Bahoum and Monique Garcia, Le Mystère du guide foudroyé – une aventure de Sherlock Holmes, Collection « Plume de Pin », Pau, 2002

Looking westwards along the Pyrenees, one finds the stirring account of Hugues-Alexandre Roy (1870) and several books by or about Count Henry Russell, that eccentric explorer of the mountains. This area also inspired a new Sherlock Holmes story by Catherine Bahoum and Monique Garcia (2002).

One may be surprised to find in the collection books on hydro-electricity, the explanation being that Aristide Bergès, “le père de la houille blanche” was born and brought up in Lorp (the next town to Saint-Lizier) where his family had a paper-mill. The Livre d’Or du centenaire d’Aristide Bergès (1933) contains two extra photographs interleaved and is a copy from the family. Their mill is now a museum of paper and printing, named after its famous son. Giles took part in its activities and also researched the splendid funeral monument to Bergès in Toulouse. An offprint of his article is included in the collection.

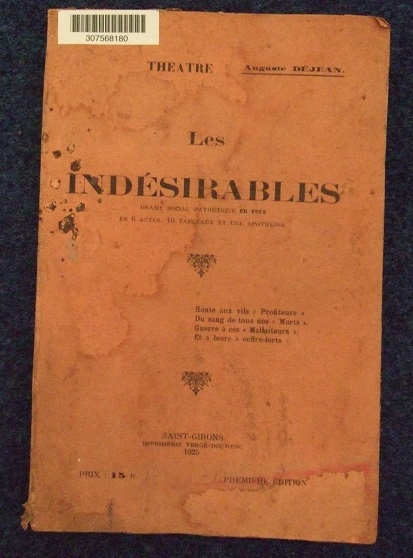

Auguste Déjean Les Indésirables, drame social pathétique en vers, en 6 actes, 10 tableaux et une apothéose, Saint-Girons : Imprimerie Vergé-Doumenc, 1925

We of course collected a number of books on local printing and publishing: a work by Louis Lafont de Sentenac (1899 reprinted 1998) and a work by Pierre Fournié (1980) as well as some of the works themselves, for instance a work by Auguste Déjean (1925) entitled Les Indésirables, drame social pathétique en vers, en 6 actes, 10 tableaux et une apothéose. One would love to find reviews of this production in the local press of the time (if indeed it was produced). Of our modern time, one finds in the collection a complete run of the very local annual periodical Vent du port, based on the area of Salau and its high pass between the Ariège and Catalonia, the scene of an annual joint gathering, the Pujada al port de Salau.

We collected a number of books on Toulouse, on its history, its architecture, its artists, and also a book by Gilles Caster (1998) detailing the main source of Toulouse’s great wealth in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries: woad, whose southern French name is pastel. It was the trade in pastel that provided the riches used to build the splendid hôtels which are still the architectural glory of the centre of modern Toulouse.

The plant and animal life of the area feature also in the collection, with for instance John and Mavis Midgley’s preliminary account of the herbarium of Adrien Faure de Fiches (2013) (a fuller publication is in hand and will follow), and various items on transhumance (the seasonal migration of people and livestock between summer and winter pastures) such as the work by Jean-Louis Loubet (2010).

The collection is very wide-ranging, and one cannot list everything here. For anyone with an interest of any kind in this area of southern France, it is well worth exploring further.

Bibliography

Les Inquisiteurs : Portraits de défenseurs de la foi en Languedoc (XIIIe – XIVe siècles), ed. Laurent Albaret, Toulouse : Privat, 2001.

Livre d’Or du centenaire d’Aristide Bergès (1833-1904), Lancey, 1933.

Saint-Girons-les-Eaux 1948.

Assémat, Pierre, Sur le chemin de Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle : les pèlerins confrères de Saint-Lizier, 1533-1710 : la quête du salut, préface de Mgr Marcel Perrier, évêque de Pamiers, 2007.

Bahoum, Catherine and Monique Garcia, Le Mystère du guide foudroyé – une aventure de Sherlock Holmes, Collection « Plume de Pin », Pau, 2002.

Barber, Giles Les Rues de Saint-Girons: les noms des rues et des édifices de la ville à travers les âges, leurs origines, ainsi que ceux des quartiers, hameaux et lieux-dits avoisinants 2004.

Barber, Lisa ‘Notre Dame du Clocher et le Clocher de Noguès à Lescure (Ariège)’, Mémoires de la Société archéologique du Midi de la France, LXVII (2007), 135-44.

Bladèr, Joan-Francés, Contes de Gasconha, prumera causida, Saint-Etienne : Lo libre occitan, 1966.

Blanc-Delmas, Germain Chronique sur Rennes-le-Château : Marie d’Etienne, le trésor oublié, Toulouse : Envolée, 1998.

Camelat, Miqueu Belina, poema de tres cantas, Sorgas – Institut d’estudis occitans, 1962.

Caster, Gilles, Les Routes de Cocagne : Le siècle d’or du Pastel, 1450-1561, Privat, 1998.

Lahondès, J. de, Les Eglises des pays de Foix et de Couserans, Lacour ré-édition, 2001.

Meritens de Villeneuve, Richard de, Lescure et ses poilus, des bancs de l’école à la croix de bois, Alliance, 2006.

Déjean, Auguste Les Indésirables, drame social pathétique en vers, en 6 actes, 10 tableaux et une apothéose, Saint-Girons : Imprimerie Vergé-Doumenc, 1925.

Dubuc, Michel Les eaux minérales d’Audinac (Ariège) 1882.

Duthil, Christian L’Almanac patoues de l’Ariejo : un almanach en occitan. Foix : Cercle occitan Peire Lagarde, 2009.

Fénié, Bénédicte and Jean-Jacques Toponymie gasconne, Editions Sud-Ouest, 1992.

Fénié, Bénédicte and Jean-Jacques Toponymie occitane. Editions Sud-Ouest, 1997.Fournié, Pierre L’Imprimerie toulousaine au XVe siècle, Toulouse, 1980.

Goodall, Scott Le chemin de la liberté : histoire et randonnée dans le Couserans.

Goodall, Scott The Freedom Trail, following one of the hardest wartime escape routes across the central Pyrenees into Northern Spain, Inchmere, 2005.

Gouy-Gilbert, Cécile & Jean-François Parent, De la houille blanche à la microélectronique : réflexions sur le patrimoine industriel de l’Isère, Lancey, s.d. (vers 2000).

Grégoire, Abbé Rapport sur la nécessité et les moyens d’anéantir les patois et d’universaliser l’usage de la langue française. 1794 (Reprinted 1995)Guillaume, Gaston Anthologie de la littérature et du folk-lore gascons, no 3 : Florilège des poètes gascons (des troubadours aux temps modernes). Bordeaux : Delmas, 1941.

Lafont de Sentenac, Louis Les Débuts de l’imprimerie dans le comté de Foix, Lacour ré-édition, 1998 ( of the Foix 1899 edition).

Laurent, Jean-Pierre Le Dialecte de la vallée de Massat : grammaire, dictionnaire et méthode d’apprentissage, 2e edn, 2002.

Laurent, Jean-Pierre Le Dialecte gascon d’Aulus, Grammaire et dictionnaire, suivi de Histoire chronologique des vallées du Garbet et d’Ustou, 2002.

Laurent, Jean-Pierre Les dialectes du Séronais – La Bastide-de-Sérou, Castelnau-Durban, le Mas-d’Azil. Grammaire et dictionnaire, suivi de : Le Séronais, histoire exemplaire d’un pays occitan, 2002.

Loubet, Jean-Louis Un site remarquable dans le Haut-Couserans : Goutets. Contribution à une connaissance du milieu montagnard et de son organisation pastorale, Nîmes : Lacour, 2010.

Midgley, John and Mavis L’herbier d’Adrien Faure de Fiches (2013).

Miramont, Christiane Au fil de l’eau, au fil du temps : les moulins de la vallée du Lens (Ariège – Haute-Garonne), 2005.

Miramont, Christiane Bruno de Ruade, évêque de Couserans, 1999.

Miramont, Christiane Le commerce du verre soufflé dans le Volvestre Ariégeois aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles : les gentilshommes-verriers et les paysans porteurs de verres, 2003.

Olive, Georges Si le Baléjou m’était conté : chronique d’une famille et d’un quartier en Couserans. 1993.

Ortet, André Un asile d’aliénés – Saint-Lizier 1811-1969, Cazavet, 2004.

Pailhès, Claudine L’Ariège des comtes et des cathares, Editions Milan, 1992.

Pailhès, Claudine Du Carlit au Crabère : Terres et hommes de frontière, Foix : Conseil général de l’Ariège, 2000.

Pailhès, Claudine Guide des Archives de l’Ariège, 1989.

Pailhès, Claudine Histoire de Foix et de la haute Ariège, Toulouse : Privat, 1996.

Pailhès, Claudine D’or et de Sang : Le XVIe siècle Ariégeois, (catalogue d’une exposition), Archives départementales, Foix, 1992.

Pédoya, Paul Autrefois Montseron : la vie – les travaux – les fêtes – l’artisanat, l’histoire – les coutumes – les traditions, 2005.

Roy, Hugues-Alexandre Les Contrebandiers du Val d’Aran, aventures d’un commis-voyageur en Espagne 1870, new. ed. 1998.

Séguy, Jean Le Français parlé à Toulouse, 3rd edn, Privat, 1978.

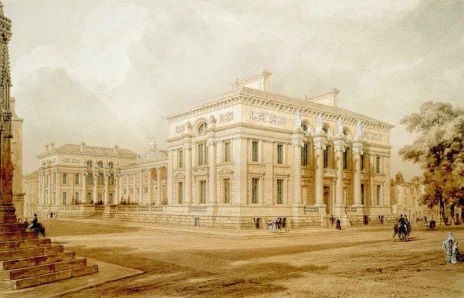

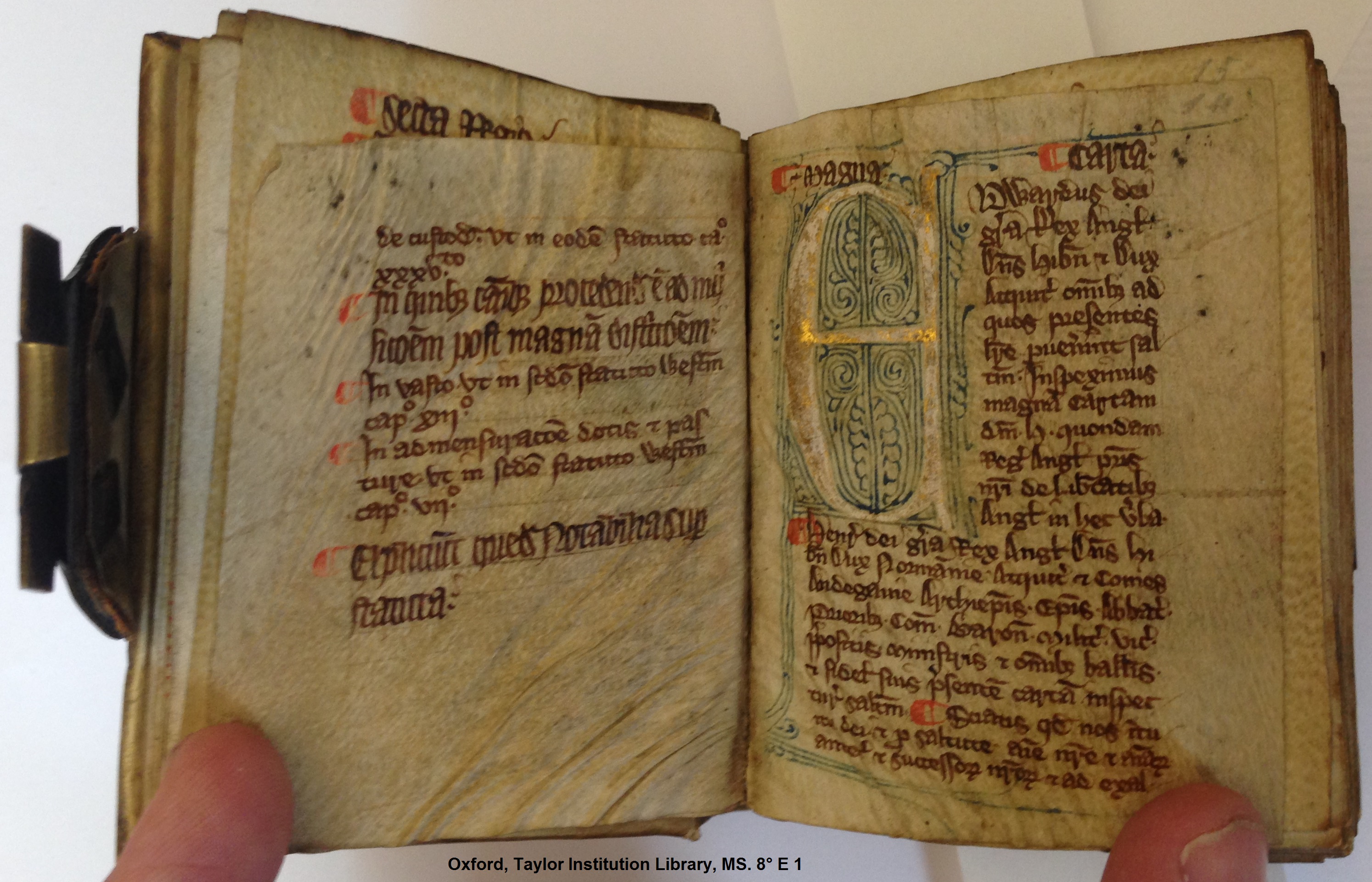

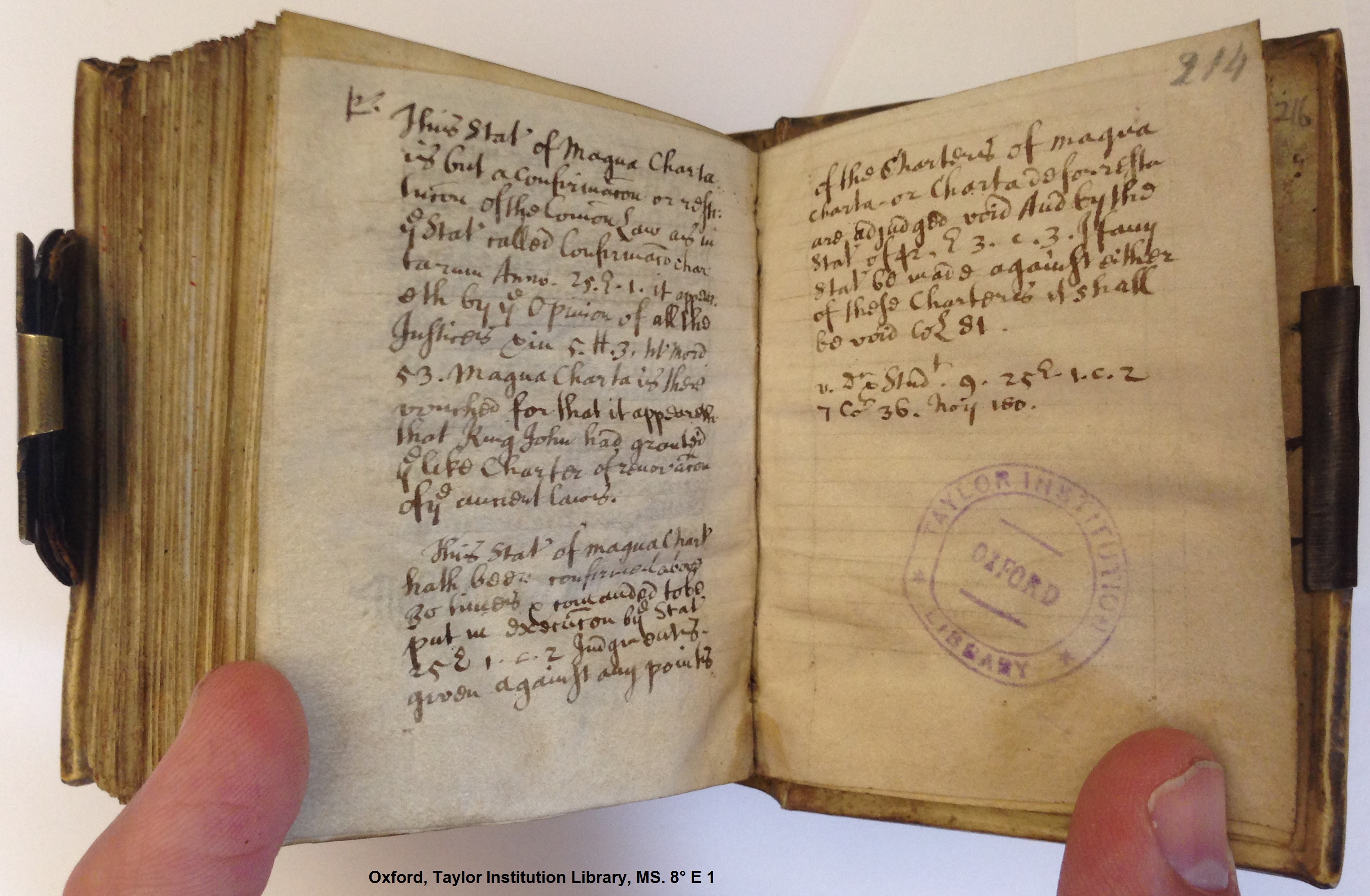

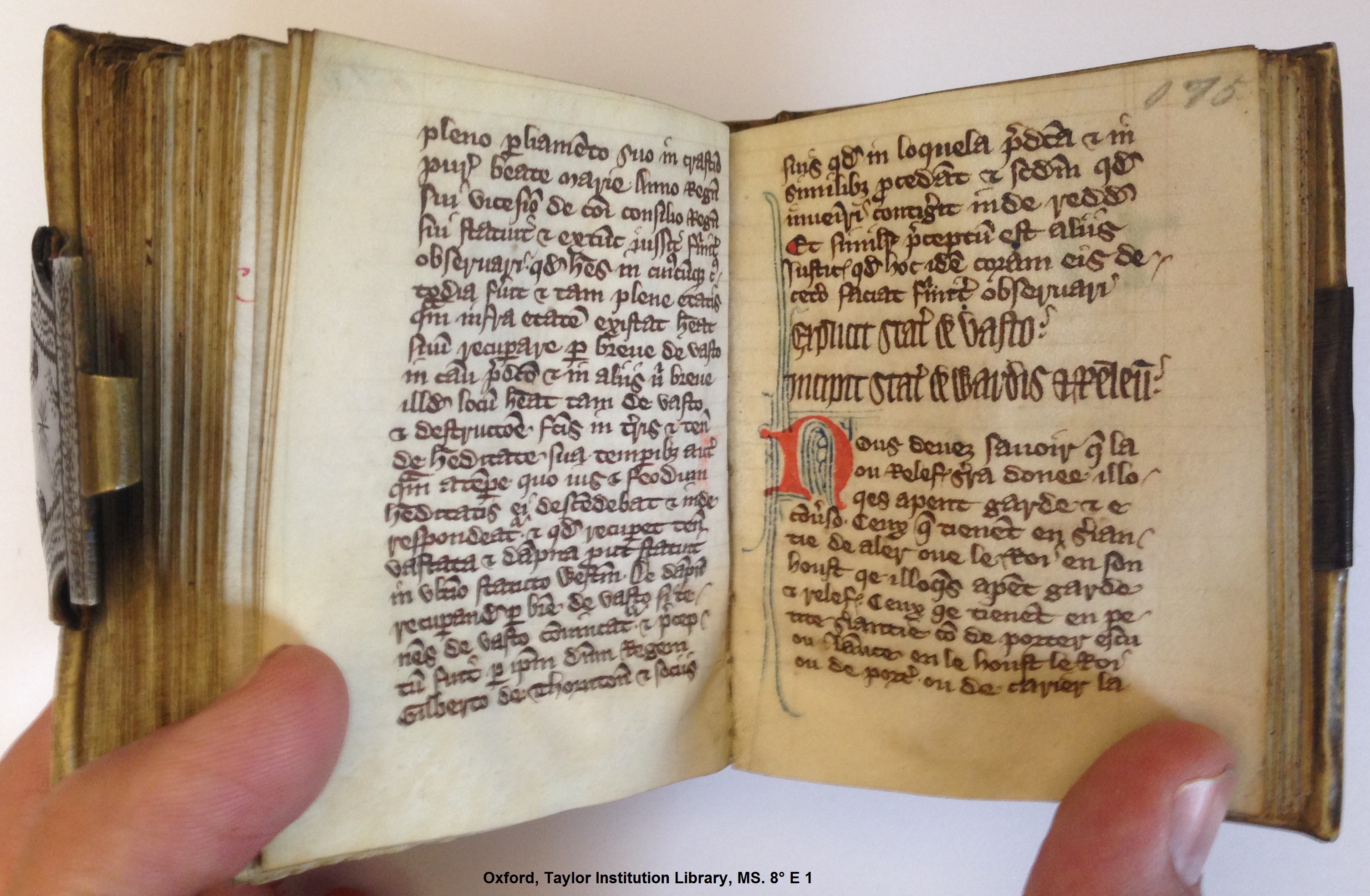

ir Robert Taylor (1714-1788), architect of the Bank of England as well as designer of many fine town and country houses, died a very rich man, leaving some £180,000 of which £65,000 was ultimately allocated to the University of Oxford “for erecting a proper Edifice … for establishing a Foundation for the teaching & improving the European Languages”.

ir Robert Taylor (1714-1788), architect of the Bank of England as well as designer of many fine town and country houses, died a very rich man, leaving some £180,000 of which £65,000 was ultimately allocated to the University of Oxford “for erecting a proper Edifice … for establishing a Foundation for the teaching & improving the European Languages”.