In recent months, Victor Jara has been in the news again owing to a trial being brought against a former Chilean lieutenant involved in his murder. The names of songwriters such as Victor Jara, Mercedes Sosa and Quilapayún continue to resonate in Latin America and around the world. Less well known (beyond Latin America) is the poetry, with the same kind of political commitment to revolution and the people’s struggle, that emerged in Nicaragua. These writings influenced subsequent generations, including pre-eminent Latin American musicians, and they play a prominent part in Latin American cultural history.

Part of the collection that the late renowned academic Robert Pring-Mill (1924-2005) bequeathed to the Taylor Institution Library depicts and encapsulates not only a crucial period of Latin American history — the revolutionary struggle of Nicaragua — but also the struggle in Latin America for meaning and representation through literature. As scholars such as Pring-Mill, and John Beverley and Marc Zimmerman (1990) have argued, while the novel became literary nationalism in Latin America, in Central America it was poetry that took on this role. In no other country in Central America did poetry have the significance and effect on national culture and identity as in Nicaragua. Testimonial writing is also a form of literature found in the publications of this collection, and has been a central tool for writers of revolutions in Central America.

The Pring-Mill collection is fascinating as a legacy of an era where committed poetry and testimonials take centre stage. The term “committed poetry”, a term penned by Pring-Mill himself, applies to a poetry that moves beyond the aesthetic to the testimonial of not only describing reality, but acting upon it and influencing the world, using poetry as a tool for social change through critique, protest, denunciation and reporting.

The Pring-Mill collection, which I was very generously given access to study, illustrates how art and revolution are closely interwoven in Latin America; and, in the case of Nicaragua, the close interweaving of art, Catholicism and revolution.

This article has been divided into three blog posts, published separately and over the course of the coming weeks. The first post introduces the collection and then focuses on Nicaraguan poetry. The second will explore serial publications and grey literature. The third will discuss testimonial literature.

Introducing the Collection

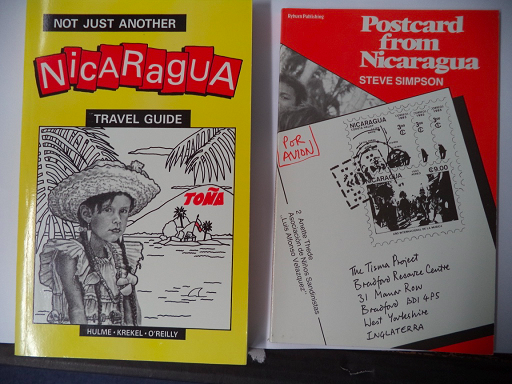

Some good introductory publications to both the collection and to Nicaragua of that time, for those who do not read Spanish, are: Not Just Another Nicaragua Travel Guide, by Alan Hulme, Steve Krekel and Shannon O’Reilly (1990); and Postcard from Nicaragua, by Steve Simpson (1987). They approach Nicaragua from a visitor’s perspective. The travel guide gives a fantastic portrait of Nicaragua, using humour, photographs in black and white and the authors’ personal opinions. Simpson’s book is the diary of his journey through Nicaragua in 1987, with a few illustrations.

A few documents were published in Germany, Russia, the UK, France and the US and show the support coming from different sectors of these countries. Many of these are from Nicaragua Solidarity Campaigns in their respective countries, while others, such as the New Left Review and the Latin American Bureau, are of a more academic nature.

Yet the most interesting of these, for me personally, is the counter-report on Central America by two UK Members of Parliament, Stuart Holland and Donald Anderson, with a preface by Neil Kinnock, entitled Kissinger’s Kingdom? (1984).

This report was the product of a fact-finding mission instigated by Neil Kinnock, the then leader of the Labour Party, as a response to the Kissinger Commission on Population and Development in Central America (its report was issued in 1984). The result is a wider and more balanced investigation into the struggles of the region and by extension is a criticism of American foreign policy at that time. It also includes criticism of the structural inadequacies in UK diplomatic representation and provides some analogies with other conflicts such as those in The Balkans and Vietnam. It is a short but fascinating insight not only into Central America but also into the mentality of the UK’s Labour Party at that time.

On the whole, the Pring-Mill collection on Nicaragua falls into three categories — which invariably overlap. The first and largest of the three, is the collection of Nicaraguan poetry; the second is the collection of grey material, ephemera and serial publications, mostly issued by the new revolutionary government of 1979 and onwards; and, finally, the testimonial writings.

Nicaraguan Poetry

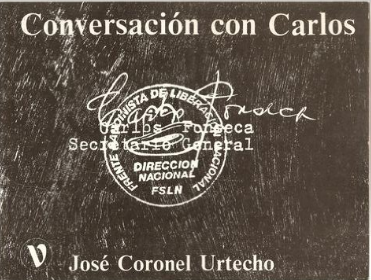

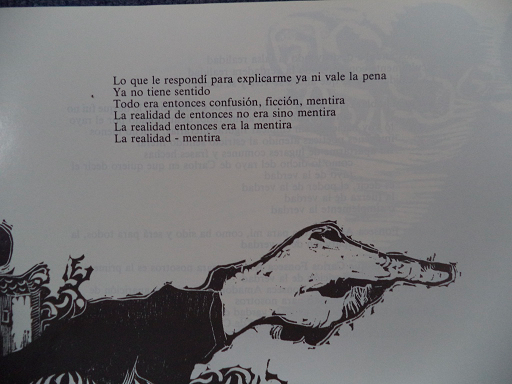

Poetry has been identified as the starting point for the Sandinista revolution, as the vehicle for inspiration and political expression of Nicaraguans. For a good introduction to the historical development of Nicaraguan poetry there is Jorge E. Arellano’s Antología general de la poesía nicaragüense (1984). It provides a survey of all the currents, trends and styles of the poetry in Nicaragua throughout the years. It starts with pre-Columbian poetry, followed by colonial poetry, then the neoclassical and romantic poets, poets contemporary with Rubén Darío, modernists, vanguard poets and post-modernists. It also includes poets on the periphery and the ‘50s generation. But to understand the importance of poetry in Nicaragua one must go back to Rubén Darío, one of the most famous poets in Latin America. He was the first to pen the term modernismo in Latin America and later the Sandinista movement established Darío as a cult figure. There are some articles dedicated to Darío in the Pring-Mill collection, but there is more emphasis on the poets who came later in the vanguard movement, poets who in fact rejected Darío and modernismo. The Vanguardia movement in Nicaragua was, according to Forster and Jackson, by far the most vital in Central America. It was the “initial impetus”, in the mid 1920s, of José Coronel Urtecho, who published a sardonic poem “Oda a Rubén Darío” which inspired a number of famous poets whose works are in the Pring-Mill collection. Urtecho is an important figure in Nicaragua both before and after the revolution and his support and enthusiasm for the new Nicaragua is depicted in his poem Conversación con Carlos, with engravings by Graciale Azcarate and Tony Capellán (1986), about his time with the founder of the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN), Carlos Fonseca.

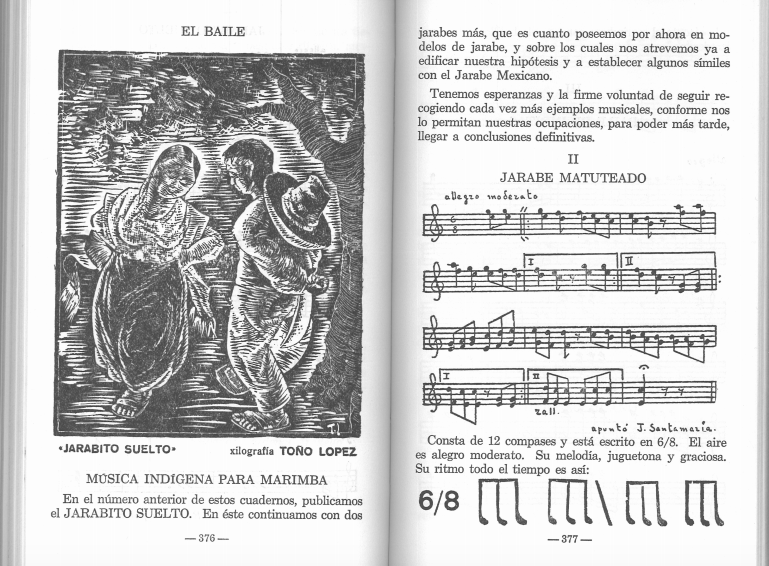

Urtecho was mentor to Ernesto Cardenal and other 1940s poets and intellectuals who were “incubated” in the celebrated poetry workshop, Taller San Lucas. Established in 1941, the Taller was the result of a group of friends brought together by their Catholicism and love of culture and is a product of the revolutionary fervor that was growing at that time, together with the vanguardista movement of which Pablo Antonio Cuadra was very much a part. The poetry workshop was organised by another significant vanguardista, Pablo Antonio Cuadra. It was Cuadra, together with Francisco Pérez Estrada, who collected the texts for Muestrario del Folklore Nicaragüense (1978), produced by the Fondo de Promoción Cultural as part of the series Ciencias Humanas.

The Fondo was set up by the Banco de América to promote Nicaraguan culture through a collection of historical, literary, anthropological and archaeological publications. Muestrario del Folklore Nicaragüense is a collection of popular and folkloric Nicaraguan stories, theatre pieces, songs, poems, legends, sayings, rhymes, myths and more.

The Fondo was set up by the Banco de América to promote Nicaraguan culture through a collection of historical, literary, anthropological and archaeological publications. Muestrario del Folklore Nicaragüense is a collection of popular and folkloric Nicaraguan stories, theatre pieces, songs, poems, legends, sayings, rhymes, myths and more.

As the introduction mentions, it is the fruit of research conducted by the editors during their work at Taller San Lucas during the 1940s. It is one of the most interesting publications in the Pring-Mill collection, due to the richness of its content, and it was clearly a long labour of love to put the book together.

As the introduction mentions, it is the fruit of research conducted by the editors during their work at Taller San Lucas during the 1940s. It is one of the most interesting publications in the Pring-Mill collection, due to the richness of its content, and it was clearly a long labour of love to put the book together.

The publication is also an extraordinary record of Nicaraguan culture. Muestrario’s editors have maintained original spellings and the vernacular used by the locals who penned the works included. Loga del Niño Dios, for example, contains words in the Mangue language of the Chorotegas, natives of the region.

The voice of Ernesto Cardenal (Minister of Culture 1979-87) can be found in a few items in the Taylorian collections, as well as in the interviews he gave for Margaret Randall’s Cristianos en la Revolución (1983) and Teófilo Cabestrero’s Ministers of God, Ministers of the People: Testimonies of Faith from Nicaragua (1983). His poem to Marilyn Monroe, as well as others, appeared in Tlaloc (Spring 1972. 3,4), a magazine produced by the students of the Department of Hispanic Studies at the State University of New York Stony Brook. A free publication distributed in Latin America and the US, it also includes poems and articles from Juan Rotta and Mario Vargas Llosa.

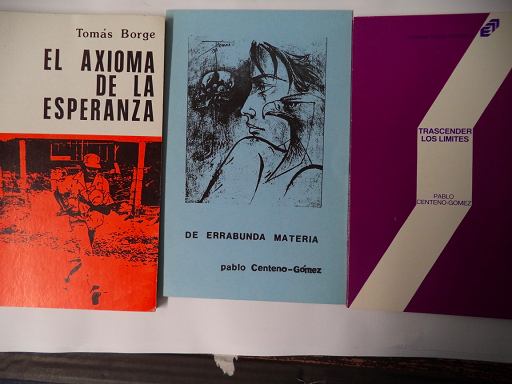

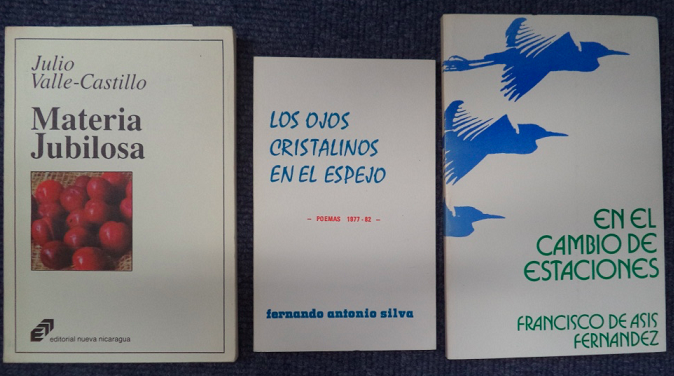

The surge and the establishment of the Sandinista movement in the ‘70s was supported by poets whose works form a significant part this collection. These authors are among Nicaragua’s most recognised poets: Fernando Silva, Julio-Valle Castillo, David McField, Tomás Borge, Pablo Centeno-Gómez and Fransisco de Asís Fernández.

The surge and the establishment of the Sandinista movement in the ‘70s was supported by poets whose works form a significant part this collection. These authors are among Nicaragua’s most recognised poets: Fernando Silva, Julio-Valle Castillo, David McField, Tomás Borge, Pablo Centeno-Gómez and Fransisco de Asís Fernández.

Also central to the Nicaraguan poetry of this time is the work of poet-combatants such as Tomás Borge and Luis Vega.

Also central to the Nicaraguan poetry of this time is the work of poet-combatants such as Tomás Borge and Luis Vega.

Yet the most striking are the writings of poet-combatants killed in the revolutionary struggle, such as Leonel Rugama (1949-1970), Ernesto Castillo Salaverry, who died at the age of twenty, and Gaspar García Laviana, a Spanish priest who became a Sandinista leader.

I am very grateful to Joanne Edwards and Frank Egerton for giving me the possibility to freely explore this collection and learn so much about a country that is seldom in the mainstream media and yet whose influence on Latin American literature and identity, in terms of its committed poetry and also its liberation theology, has been so powerful.

Natalia Bermúdez Qvortrup

University College of Oslo and Akershus

Intern, Social Science Library, Bodleian Libraries

Further reading

Arellano, Jorge Eduardo (1997) Literatura Nicaraguense. Managua: Ediciones Distribuidora Cultural.

Beverley, John and Marc Zimmerman (1990) Literature and Politics in the Central American Revolutions. Austin: University of Texas.

Forster, Merlin H. and K.David Jackson (1990) Vanguardism in Latin American Literature: An annotated Bibliographical Guide. New York: Greenwood Press.

Pring-Mill, Robert “ Both in Sorrow and in Anger: Spanish American protest poetry” Cambridge Review vol.91/ 2195 (1970).