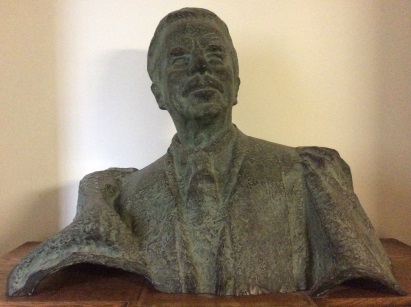

Readers who use the Taylorian’s German collections might have come across rare books and manuscripts whose shelfmarks begin with ‘Fiedler’. Considering the incredible breadth and value of the Fiedler Collection for the study of German literature from the last five hundred years or so, it is hardly surprising to learn that the donor was a distinguished Professor of German. Hermann Georg Fiedler served as Chair of Oxford’s German department from 1907 until 1937, leading the department through the challenges of the First World War and supervising the construction of the extension, along St. Giles’, of the Taylorian’s Teaching Collection (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004). Today he is commemorated with a large bust.

Less well-known than Fiedler’s Germanic acquisitions and less publicly apparent than the bust, however, is the stunning collection of autographs assembled by his family during the nineteenth century. After their donation to the Taylorian by Fiedler’s daughter, Herma, during the 1960s (Sutherland, 1970: i), these manuscripts had lain relatively quietly in our Rare Books Room, until an email enquiry from a Danish academic caused them to be taken out and re-examined in 2017. Many library staff had not encountered the manuscripts before, so there was great excitement at the discovery of just how many household names had given samples of their handwriting to fill the pages.

The manuscripts are stored in five boxes (shelfmarks MS.8o.E.17-MS.8o.E.21) and are referred to as the Peyton-Harding Collection, in recognition of Herma Fiedler’s relatives, who collected most of the autographs. Fiedler had met his wife, Ethel Harding, when she was a pupil of his at the University of Birmingham in the late nineteenth century (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004). Ethel’s father, Charles Harding, was a highly influential solicitor and philanthropist who funded many initiatives including scholarships at the University and served regularly on organising committees for the Birmingham Music Festival (Carley, 2006: 226). Charles Harding’s younger daughter, Emily, was married to a wealthy businessman named Richard Peyton (Harding Family Tree (Detailed), 2017). As a passionate music aficionado, Peyton chaired the Birmingham Festival and financed the University’s Chair of Music position (on condition that his friend, Sir Edward Elgar, took on the role) (Moore, 1999: 446). With their widespread musical, academic and social connections, the Peyton, Harding and Fiedler families were well situated to build an autograph collection showcasing some of the most illustrious names of their time.

This blog post is necessarily limited to covering just a few of the highlights of the collection, but any registered reader interested by what follows can ask to see the boxes by filling in a request slip at the Taylorian Enquiry Desk.

Queen Victoria’s Poignant Thanks (MS.8o.E.17, p.1)

The collection begins in spectacular fashion: the first letter you see when opening the first box was written by Queen Victoria. On Windsor Castle headed notepaper, it addresses an open message of thanks to the women of the United Kingdom for funding a statue in memory of the late Prince Albert. As the date of the letter is 22nd June 1887, the day chosen for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee celebrations, it would seem that the statue referred to is the equestrian statue of Albert in Windsor Great Park (Roberts, 1997: 379).

The statue of Prince Albert funded by UK women to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee (1887) |

© Copyright Alan Hunt and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

Women across the UK had been given a leaflet inviting them to contribute between a penny and a pound to a Jubilee gift of the Queen’s choice, ‘in token of loyalty, affection, and reverence towards the only female sovereign who, for fifty years, [had] borne the toils and troubles of public life, known the sorrows that fall to all women, and as a wife, mother, widow, and ruler, [had] held up a bright and spotless example to her own and all other nations’ (Boucherett et al. (eds)., 1979: 82). It is poignant to think that the same Queen who had been too grief-stricken by her husband’s death to celebrate her Silver Jubilee, and had kept a strict regime of mourning for many years, chose to mark one of the few public occasions of her later life through a statue of Albert.

Hans Christian Andersen’s African Reverie (MS.8o.E.18, p.64)

A highlight of the second box in the collection is undoubtedly Hans Christian Andersen’s meticulously presented extract from his 1864 travelogue In Spain (translated into English by Mrs Anna S. Bushby). Andersen is of course best known for his fairy tales, which include The Ugly Duckling, The Little Mermaid and The Snow Queen. However, he was also an enthusiastic writer of plays, poetry and non-fiction. In Spain is his diary of an extended tour of the Iberian country, punctuated by few days’ stay in Tangier, Morocco, with his friends the Drummond Hay family, representatives of the English and Danish governments (Andersen, 1864: 189).

Despite accounting for only one chapter of the book, Andersen’s time in Africa is an emotional high-point of his journey. Before the extract acquired for the Peyton-Harding collection, he writes ‘Delightful, never to be forgotten days did I pass [in Tangier], forming a new and rich leaf in the story of my life’ (Andersen, 1864: 183). After a varied programme of exploration, he concludes the chapter by asserting that ‘Our sojourn on the African coast had been the most interesting part of our travels hitherto’ (Andersen, 1864: 205).

The Peyton-Harding handwritten extract (which corresponds with parts of pp.87-88 in the 1864 printed version) depicts a rare, sombre moment on the balcony of the Drummond Hays’ villa. Andersen lights a cigar and finds his thoughts being led towards some of the darker aspects of Africa’s past. He imagines a girl picking tobacco in Cuba, ‘a kings [sic] daughter from hot Africa, now a slave in a larg [sic] West India island.’ In his mind’s eye, the girl sheds a tear in remembrance of her African childhood, which soaks into the tobacco leaf she is holding, and remains embedded there as the leaf is transformed into Andersen’s own cigar. From the lit cigar, the tear ‘freed itself’ in the smoke, ‘it raised itself in its fatherland, and flew over the Atlas Mountains to the unknown inner region. The soul in the tear was at liberty in thoughts [sic] homeland.’ This poetic expression of the cruelty and unfairness of the slave trade reflects a concern which Andersen had already explored in his 1840 play The Mulatto, and which evidently still haunted him (Zipes, 2005: 21).

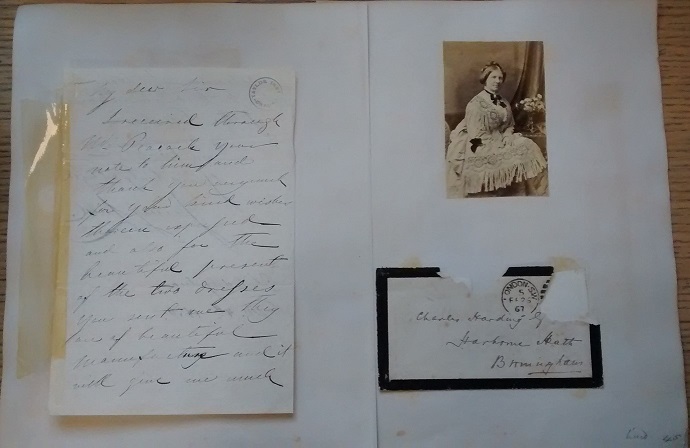

Jenny Lind’s Glamorous Lifestyle (MS.8o.E.17, pp.44-45)

A note in the first box from the highly successful Swedish opera singer Jenny Lind is not only an evocative piece of memorabilia in its own right, but also makes an interesting point of comparison with the Andersen manuscript. After meeting Lind in the early 1840s and corresponding with her, Andersen developed a level of adoration for her that has led his biographers to agree unanimously that she was his ‘great, unrequited love’ and ‘a loyal and recurring figure’ in the fantasy worlds he portrayed through his writing (Andersen, 2005: 312). She never reciprocated his feelings, but he continued to think of her and kept a bust of her in his home until his death (Andersen, 2005: 312).

The letter in the Peyton-Harding collection seems illustrative of how widespread such admiration for Lind was among her audiences. Dated 4th December 1850, when Lind was touring the USA under the management of famous showman PT Barnum (Rosenberg, 1851), it is addressed to an unspecified ‘Sir’ but its purpose is to pass on thanks to a ‘Mr Peacock’ for ‘two dresses…of beautiful manufacture’ that he had given her. She promises gratefully that she will wear them on stage ‘in kind remembrance of the Donor.’

An eyewitness account of the US tour describes how Lind was inundated with similar gifts, as well as messages and visits from fans. They arrived at the rate of literally ‘one every other minute’, to the point that Lind felt at times as if she were being ‘torn to pieces’ by the clamour of attention (Rosenberg, 1851: 72-73). For her US audiences, she was clearly one of the most exciting celebrities of the time.

Professor Fiedler’s German Travels with the Future Edward VIII (MS.8o.E.19, pp.42-45)

The third box of autographs holds some memories more personal to the Peyton and Harding families, as Professor Fiedler’s letters home from a very important trip to Germany are preserved in this box. Between 1912 and 1914, Fiedler was German tutor to Edward, Prince of Wales (1894-1972), an undergraduate at Magdalen College, who would be crowned as King Edward VIII, abdicating eleven months later in order to be able to marry divorcee Wallis Simpson). The young Prince had the opportunity to improve his language skills by visiting Germany in spring and summer 1913, and Fiedler went with him (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004).

Fiedler’s letters, which are addressed to his sister-in-law Mrs Peyton, demonstrate both a great fondness for the Prince and a reverence for the glamorous world of royalty. On 28th March 1913, he refers to Edward affectionately as ‘our Prince’, and claims that ‘He is such a dear fellow’, who often confides in Fiedler privately. The two in fact remained in contact long after the tuition arrangement was over (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004). Mixed with the feelings of warm friendship, however, one can also sense Fiedler’s awe at the regal lifestyle. In his letter of 28th March, he relates how Edward ‘wore his [ceremonial] Garter at dinner and looked splendid’. In an earlier letter (23rd March 1913), he eagerly lists all the German dignitaries the pair have met or are due to meet, and excitedly concludes by saying that he ‘must hurry back’ to their party. In hindsight, there is a very poignant side to the Easter festivities Edward enjoyed with his German counterparts, as the two countries went to war with each other only a year later.

Perhaps the most exclusive souvenir of the trip, however, is a short note to Professor Fiedler written by the Prince himself to demonstrate his (somewhat novice) German language skills (see transcription and English translation below).

Für Professor Fiedler

Würden Sie gern um 8 uhr einen Spatziergang machen bis 9 uhr? Nur wenn es nicht zu früh ist. Ich habe das Frühstück um 9 uhr bestellt für drei.

E

To Professor Fiedler

Would you like to go for a walk from 8 o’clock until 9? Only if it isn’t too early. I have ordered breakfast for three at 9 o’clock.

E

Misunderstandings with George Bernard Shaw and Algernon Charles Swinburne (MS.8o.E.21/B)

The fifth and final box is organised differently from the others: the manuscripts do not have individual page numbers, but instead are grouped into categories according to the occupations of their writers. Group B (‘English Writers’) contains two somewhat amusing examples of mishaps in Professor Fiedler’s academic career.

In 1928, George Bernard Shaw was already a Nobel Prize laureate who had written some of the most renowned plays of his time – including, arguably, his most enduring work, Pygmalion, which is still frequently performed today and was the inspiration for the musical My Fair Lady (Frenz (ed.), 1969: 229). Unfortunately, he did not feel that his abilities extended so far as to allow him to comment on writers from abroad. His note to the Taylorian, dated 15th May 1928, states in a rather alarmed and curt manner that it is not his job to give a lecture at the Taylorian, because he does not speak a word of Norwegian. Presumably he had been invited to speak on Ibsen.

In 1901, meanwhile, it seems that Professor Fiedler was misled by the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne. As an adult, Swinburne became associated with passionate and erotic poetry (Poetry Foundation, 2017), but he reveals in the letter below that his youthful intellectual interests were focused elsewhere. Dated 12th February 1901, it reads, ‘Dear Sir, I am quite sorry you have had so much trouble about Maistre Gaget. I must confess that he & his book, as well as the legend of the leper, were pure inventions of my own at a rather early age, when I was fond of trying my hand at imitations of mediaeval French prose & Latin verse. Yours apologetically, A C Swinburne. ‘

As mentioned above, this post covers only a small selection from a large and wide-ranging collection. The Peyton, Harding and Fiedler families managed to collect many more fascinating items that cannot be included here, such as handwritten staves of music by Sir Edward Elgar, Edvard Grieg, Antonín Dvorák, Franz Lizst and Sir Arthur Sullivan; the signatures of Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell and Rudyard Kipling; and various notes and calling cards from political and military luminaries of the time. The collection is well worth exploring further and the Taylorian is certainly fortunate to be its owner.

————–

Jessica Woodward

Formerly Graduate Trainee at the Taylorian, now Assistant Librarian at Mansfield College.

References

Primary Source

Peyton, Harding and Fiedler families (19th C.) Peyton-Harding Autograph Collection. Donated to the library by Herma Fiedler. [Taylorian MS.8o.E.17-21]

Secondary Sources

Andersen, H. C. (1864) In Spain, tr. by Mrs. Bushby. London: [publisher unknown]. [Bodleian (OC) 203 c.261]

Andersen, J. (2005) Hans Christian Andersen: a new life. New York and London: Overlook Duckworth. [Bodleian M07.E05693]

Boucherett, E. J. et al (eds.) (1979) The Englishwoman’s review (of social and industrial questions). New York: Garland Publishing. [Available online via SOLO]

Carley, L. (2006) Edvard Grieg in England. Woodbridge: Boydell. [Bodleian M06.E11817]

Frenz, H. (ed.) (1969) Literature 1901-1967. Amsterdam and New York: published for the Nobel Foundation by Elsevier Publishing Company. [Bodleian 3961 d.157]

Harding, N. (2017) Harding Family Tree (Detailed). [Available online at https://sites.google.com/site/hardingofpackington/home/family-tree-detailed#_Toc307562807] Accessed 12th May 2017.

Moore, J. N. (1999) Edward Elgar: a creative life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Bodleian Lower Gladstone Link M99.E10357]

Santini, D. (2004) ‘Fiedler, Hermann Georg’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [Access online, from within the University network, via SOLO]

Roberts, J. (1997) Royal landscape: the gardens and parks of Windsor. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Bodleian Lower Gladstone Link M98.A01556]

Rosenberg, C. G. (1851) Jenny Lind in America. New York: Stringer & Townsend. [Available online via SOLO]

Sutherland, D. M. (1970) Catalogue of autograph material acquired by the library during the years 1950-1970. Oxford: Taylor Institution. [Taylorian ZA.2226.6 / REF.M.1.C]

Zipes, J. (2005) Hans Christian Andersen: the misunderstood storyteller. New York and London: Routledge. [Bodleian M06.F03880]