Viewing Walter J. Strachan’s Livre d’artiste Collection with Geoffrey Strachan

Remember the Taylor Institution Library in the days before Covid? A busy place, full of academics, students and visitors en route to lectures — and to the library. Indeed, some individuals were attending seminars and other events at which the library’s special collections were on view. In this post we look back twelve months, to (as you will discover if you read on) one of our more memorable special collections events……

In May 1945, less than a fortnight after the German surrender marking the end of World War II in Europe, a British schoolteacher took his French language students on a trip to London. They were going to the National Gallery (whose collection of paintings had been transferred to Wales for the duration of the War) to see an exhibition of livres d’artistes, or artists’ books, a still relatively minor avant-garde art form imported from the Continent — principally Paris; one can assume that for the students the exhibition was little more than an excuse to experience a post-VE Day London still ecstatic with the new, incompre-hensible peace in Europe.

Whatever the students thought of it, the exhibition was nothing short of life-changing for their teacher, Walter Strachan, who described first seeing the livres d’artistes as simply “over-whelming”. He took his pupils home and returned not long after, traveling to Paris as soon as the Channel was re-opened to tourists. There he met the artists, authors, printmakers, typesetters and publishers in situ, with a dream of stimulating interest in the livre d’artiste genre back home in the UK. Strachan’s advocacy was greeted with open arms in France and he returned home rich with examples of recently-created works to show to potential collectors, such as V&A curators and librarians who, thanks to his urging, ultimately acquired over 60 such pieces. This trip was followed by another, and then another, until an annual tradition began.

By the time he was 80, Strachan had formed a working collection of over 250 complete and semi-complete livres d’artistes, spanning works incorporating lithographs designed by Pierre Bonnard (1900) to Pierre Tal-Coat etchings (1983). Strachan sought a permanent home for his collection, where it could be used as it had been throughout his life—not untouched in a collector’s drawer, but as a living body of work that would continue to promote the genre as a wildly creative and important art form.

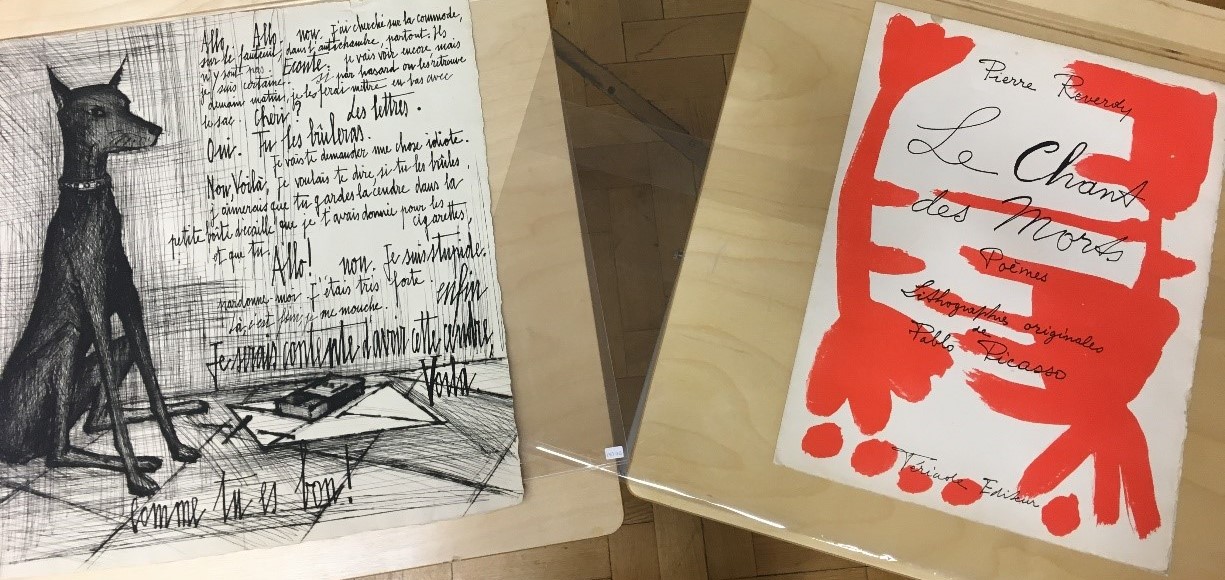

Jean Cocteau. La voix humaine. Illustrated by Bernard Buffet (Paris: Parenthèses, 1957. Pierre Reverdy. Le chant de morts (Paris: Teriade, 1948)

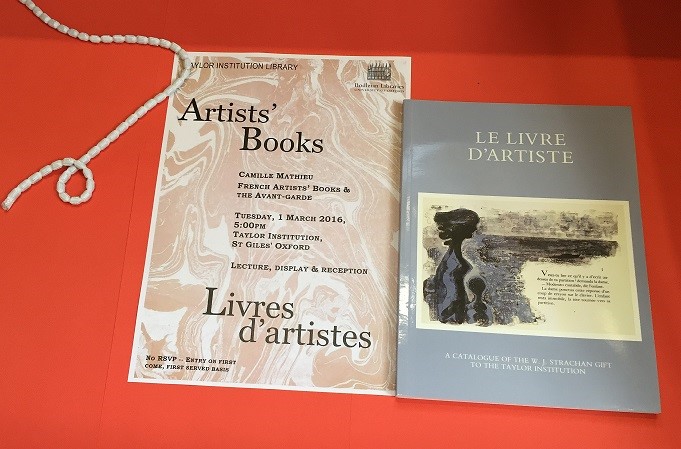

In 1987, after a commemorative exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum, Strachan found that home at the Taylor Institution Library. Thirty-two years later, the collection is still used by both researchers and students from across the University—and occasionally shown to visiting groups, as happened in July 2019.

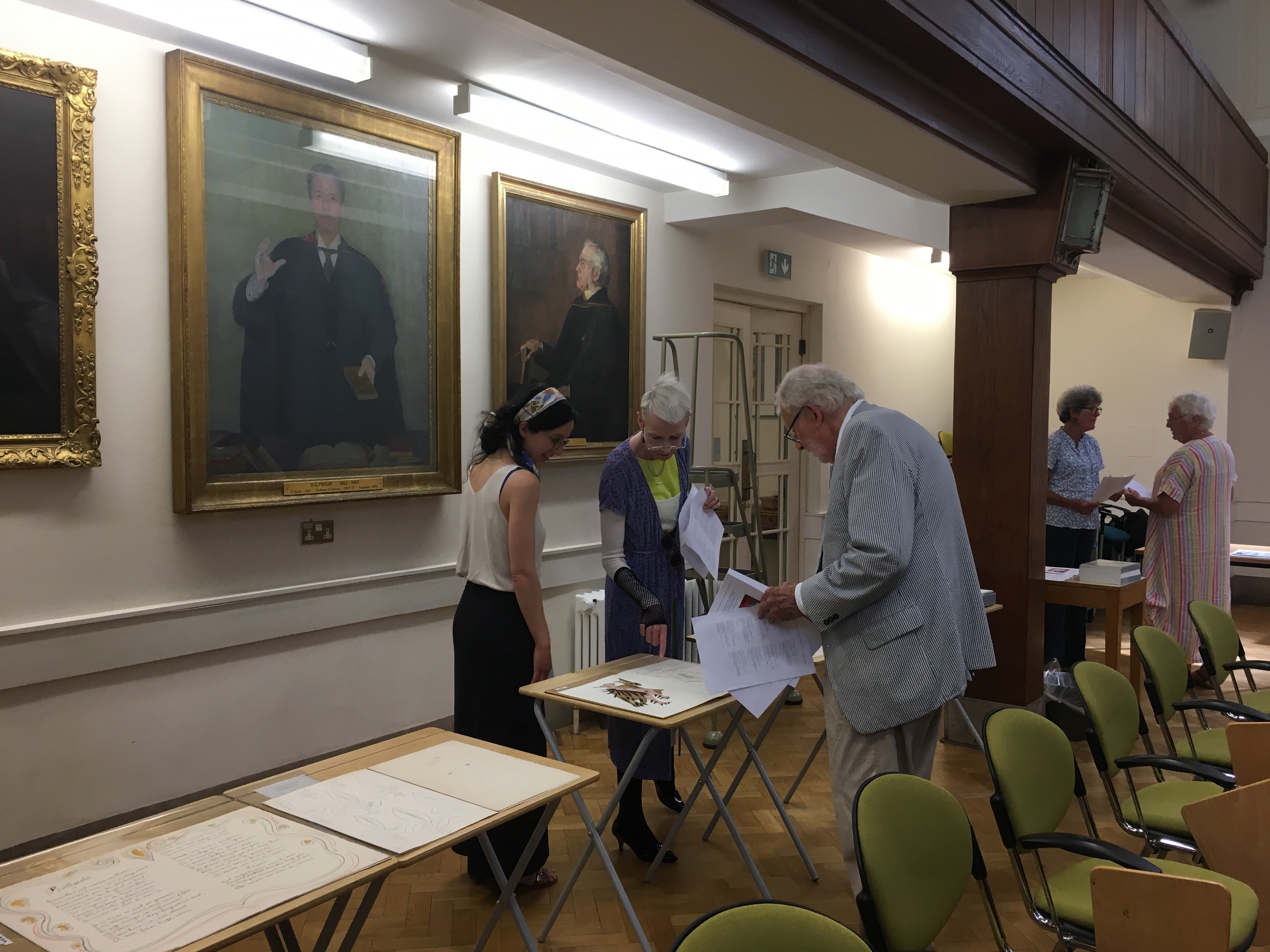

It was the hottest day on record in Oxford’s history: not the kind of day one would choose to mount a display of our livres d’artistes. With the support of our premises manager, Piotr Skzonter—without whom the whole display would have fallen apart—we exhibited a selection of pieces chosen for a visit by the Charlbury Art Group, led by Walter Strachan’s son, Geoffrey. The Taylorian’s lecture hall was mercifully cool, its high windows, blinds and thick walls protecting us from the inferno outside; still, we wondered, given the heat would anyone come?

- Viewing the display

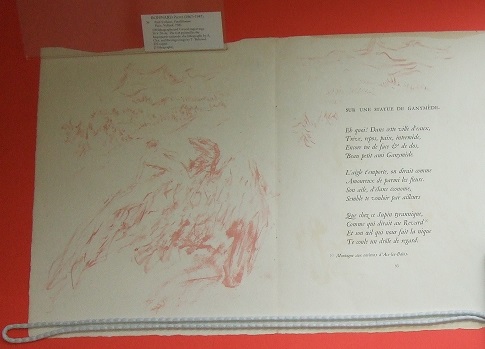

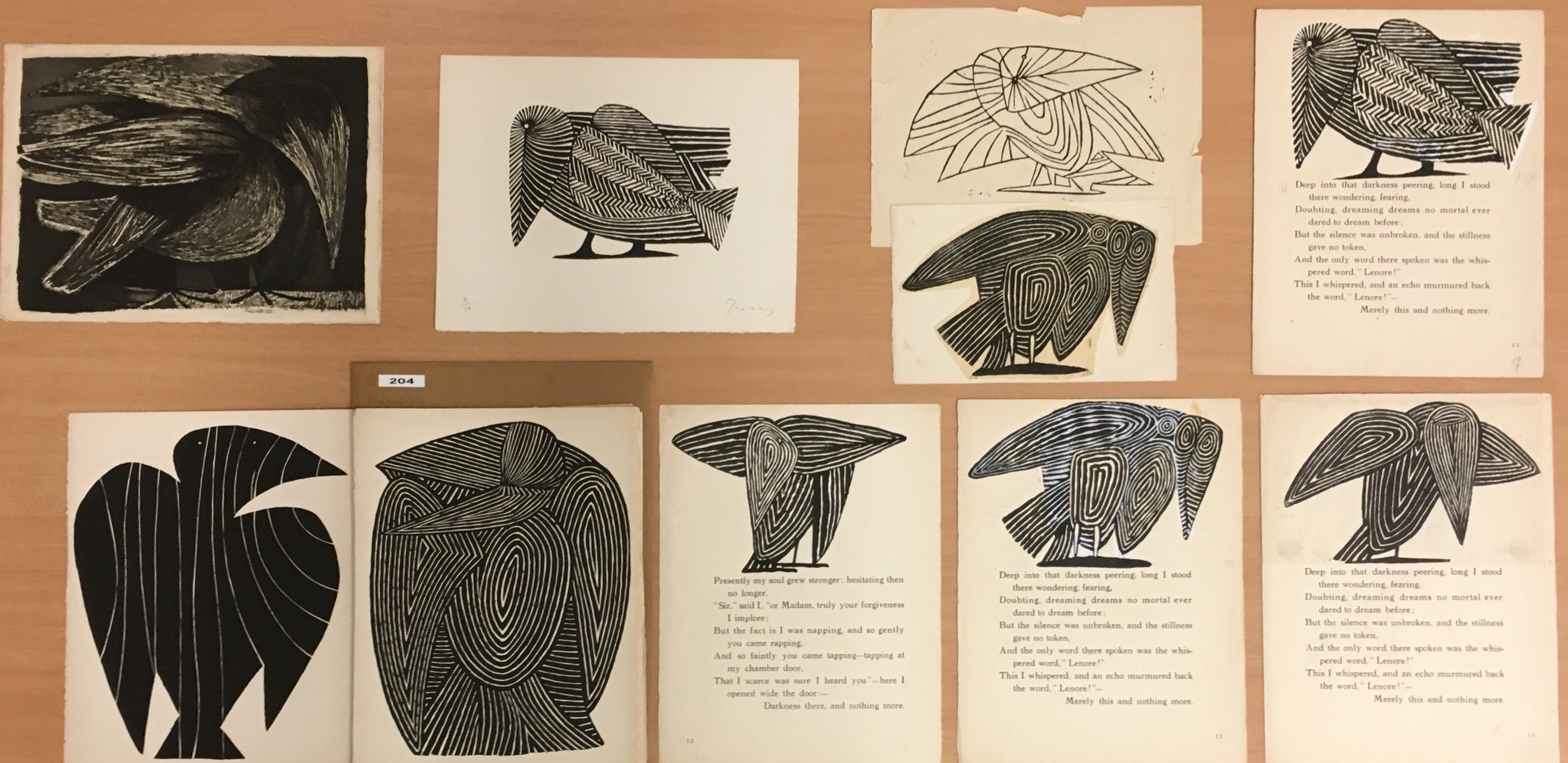

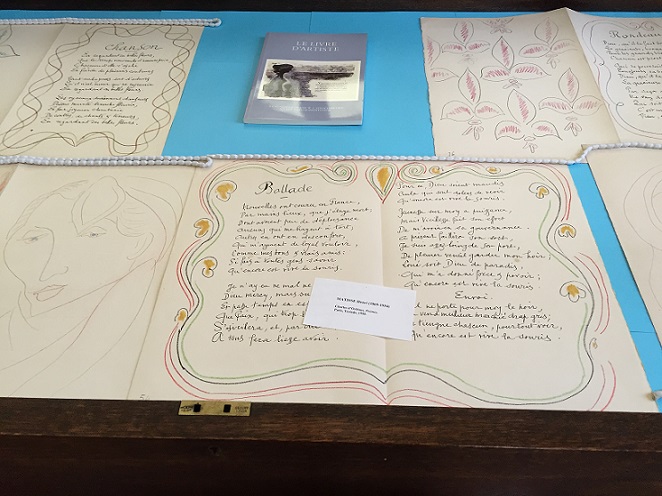

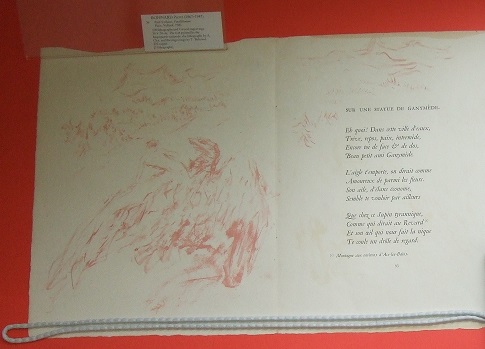

Slowly, the hall filled up and, despite the temperature, soon the whole group was with us. The afternoon was introduced by Clare Hills-Nova, Librarian in Charge, Sackler Library, where the collection is now held (on long-term loan) in a climate-controlled environment. Clare noted that this was the largest livre d’artiste event that the Taylor had yet hosted. As library staff – together with Geoffrey Strachan — brought together selected works to show our visitors, we discovered pieces that we had never seen before; one example—Mario Prassinos’ rendering of Edgar Allen Poe’s The Raven, with its many iterations of the raven image—reminding us what an unparalleled didactic tool the collection serves for University of Oxford researchers and students. Since Strachan’s pieces were often page proofs, ‘off-cuts’ and/or working drafts, or even rejects from the artists (the finalized works too valuable to give away) our collection reveals the thought processes behind livres d’artiste production and the 30 works we showed that day represented a microcosm of this artistic dynamic.

Alongside our selections of semi-complete artists’ books were a few complete works, either owned by the Taylorian or held by other libraries, to show how each of the incomplete works fitted into the finished whole, and what might have changed between Strachan’s visits with the artists and their books’ completion.

Geoffrey Strachan gave a stimulating talk, setting the stage by walking us through his father’s journey from that momentous National Gallery exhibition to his pivotal role promoting the livre d’artiste in Britain. That we have this collection is not only thanks to his father’s passion, Strachan reminded us, but also thanks to the generosity of the artists he met.

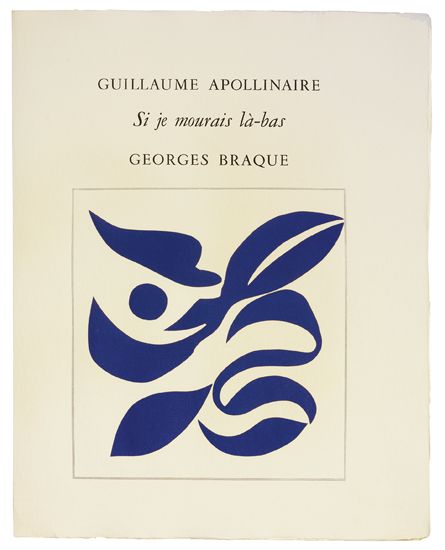

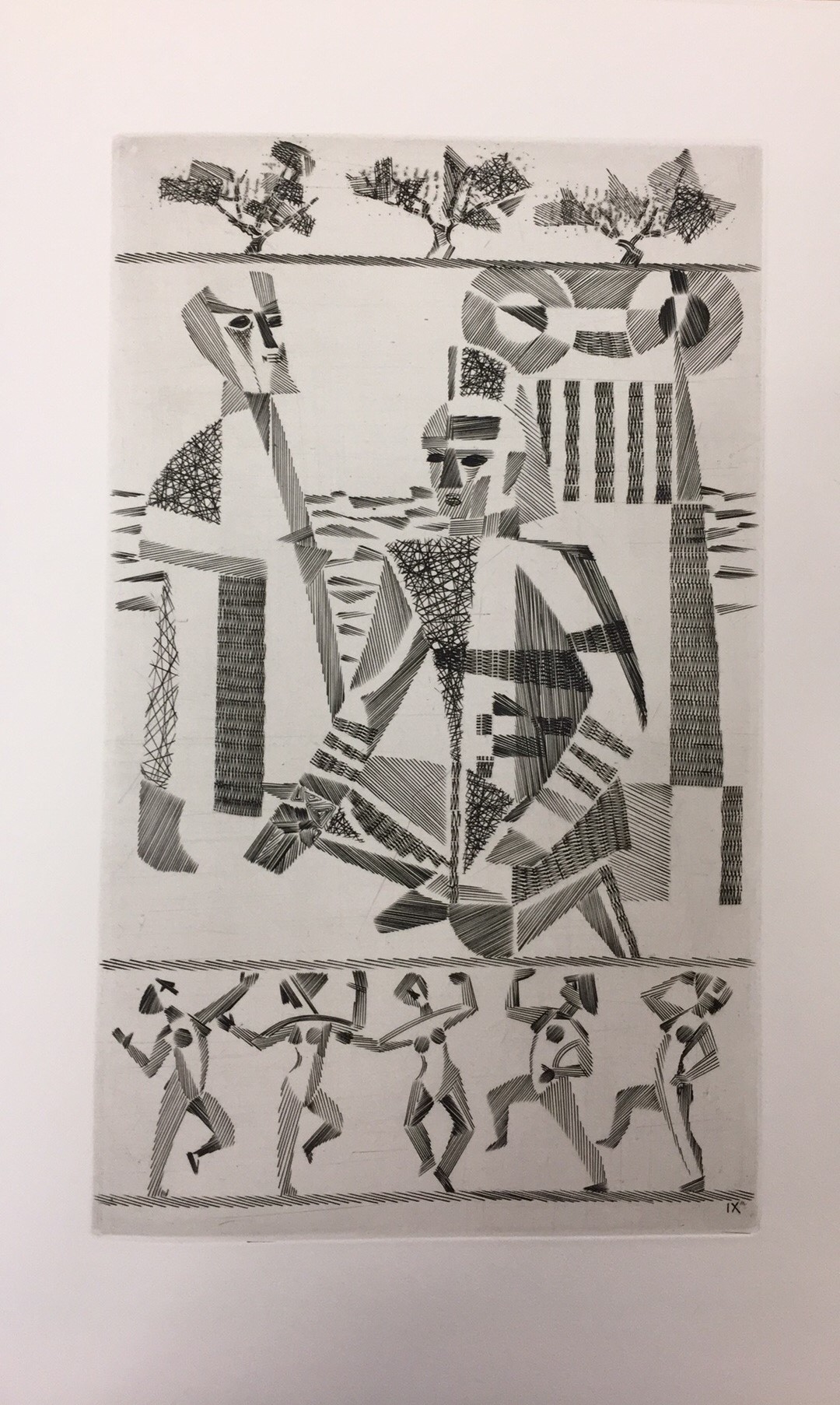

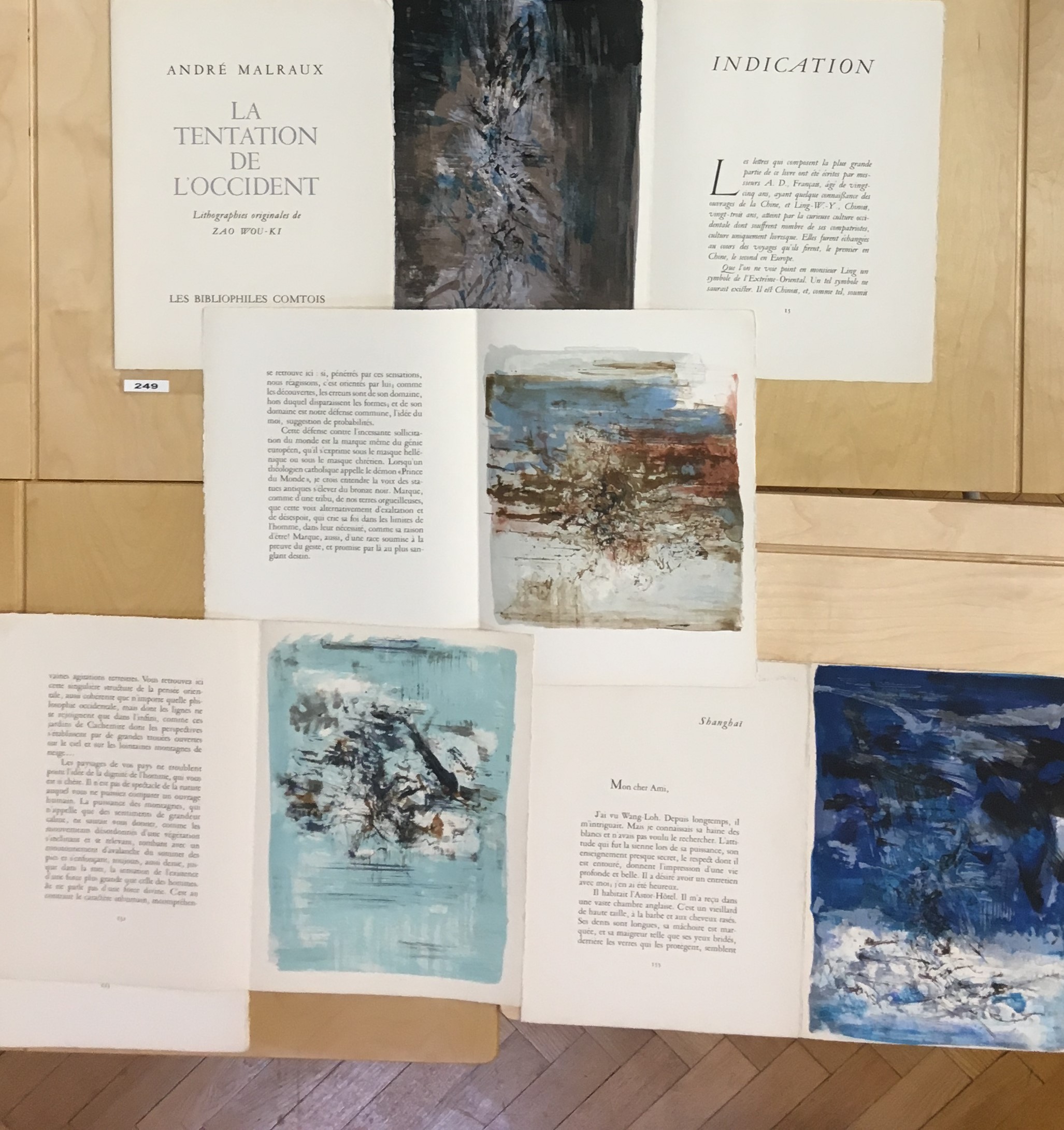

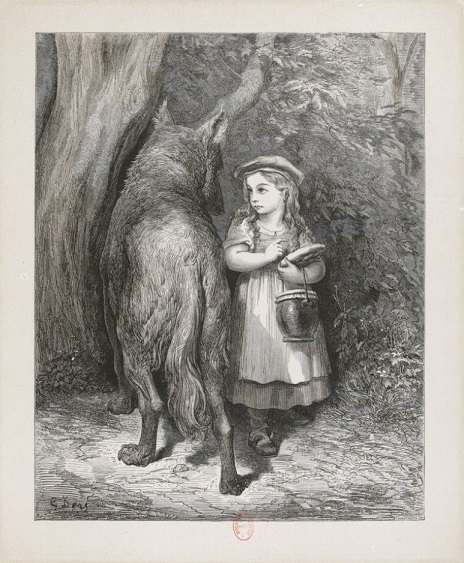

With that in mind, the group was invited to explore the display, spread across the shaded lecture hall. Grouped by theme and/or period, the pieces held different attractions for different viewers; some mulled over the more famous pieces such as Pierre Bonnard’s illustrations for Parallèlement, by Paul Verlaine, or Georges Braque’s images for Si je mourais là-bas by Guillaume Apollinaire; while others were drawn to lesser-known works such as the compelling line-images of Agamemnon, illustrated by Polish émigré Abram Krol or the fairy-tale-esque etchings in Hélène Iliadz’s Brigadnii – Un de la Brigade, by another émigrée artist, the Ukranian Anna Staritsky. One of the most popular works was French cultural icon (and Minister of Culture) André Malraux’s La Tentation de L’Occident, illustrated by Zao Wou-Ki (an émigré from 1940s China), combining emotive and explosive abstract images with an elegant typographical design.

- Hélène Iliadz. Brigadnii = Un de la brigade. Illustrated by Anna Staritsky (Paris: H. Iliazd, 1982)

- André Malraux. La tentation d’Occident. Illustrated by Zao Wou-ki (Paris: Les Bibliophiles comtois,, 1962)

While each work had a magic of its own, viewing the display as a whole had a kaleidoscopic effect, showing the variety of technique, colour, authors and artists within a once side-lined genre. This was magnified further by these artists’ books’ donation home: a library where the content of much-read and consequently battered texts normally takes precedence over the visual materiality of the publications themselves; a library temporarily transformed into a gallery for books whose physicality is their raison d’être. It is easy to see how this radical and at times very powerful marriage of word and image, content and form swept Strachan away in a lifelong love affair that we, with much appreciation, are still learning from.

Alex Zaleski, Library Assistant, Taylor Institution Library

Photo credits: Clare Hills-Nova, Justine Provino and Alex Zaleski

Further reading

Le livre d’artiste: a catalogue of the W.J. Strachan gift to the Taylor Institution: exhibited at the Ashmolean Museum, Ox, 1987 (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum and Taylor Institution, 1987).

W.J. Strachan. The artist and the book in France: the 20th century livre d’artiste (London: Owen, 1969)