In conjunction with the one-day interdisciplinary conference, ‘Women, Authorship, and Identity in the Long Eighteenth Century: New Methodologies’ (held on Saturday, 17th June, at the Taylor Institution and TORCH), the Taylorian hosted an exhibition entitled ‘The Unnatural Life at the Writing-Desk’: Women’s Writing across the Long Eighteenth Century. The exhibition was curated by Dr Kelsey Rubin-Detlev, Joanna Raisbeck and Ben Shears. The exhibition catalogue is available at this link.

The exhibition aims to display the contribution that women writers (broadly conceived) made to a variety of fields in the long eighteenth century, with sections, among others, on science, focussed on Emilie Du Châtelet; drama, with works by Hannah More and Charlotte von Stein; and letters. The aim is to move beyond entrenched or prescriptive ideas of the areas in which women could operate—including for example, translation—and to offer a nuanced perspective on the breadth and depth of women’s writing across Europe. The exhibition draws in the most part on volumes held in the special collections of the Taylor Institution Library, but also on the antiquarian collections of Somerville College, and showcases the work of, among others, Mary Wollstonecraft, Sophie Mereau, Fanny Burney, Françoise de Graffigny, and Catherine the Great.

Below are a few examples of some of the works exhibited, which have been chosen for how they differ from clichés of women’s writing in the eighteenth century, such as women primarily producing (epistolary) novels and translations. These include the German writer Benedikte Naubert was important for the development of the historical novel, Charlotte von Stein, who is better known for her relation to Goethe than her dramas, and an edition of Catherine the Great’s dramas. The volumes in themselves are intriguing historical and cultural artefacts:

Benedikte Naubert

- Benedikte Naubert, Herman of Unna: a series of adventures of the fifteenth century, in which the proceedings of the secret tribunal under the emperors Winceslaus and Sigismond are delineated, 2 vols (Dublin: William Porter, 1794) FIEDLER.J.3375.01

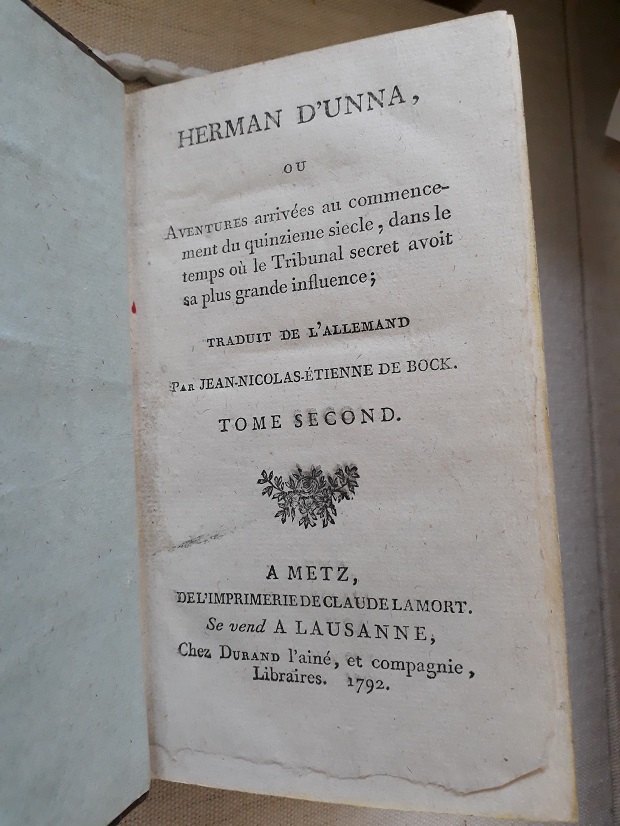

- Jean-Nicholas-Étienne de Bock (tr.), Benedikte Naubert, Hermann d’Unna, ou aventures arrivées au commencement du quinzieme siecle, dans les temps où le Tribunal secret avoit sa plus grande influence, 2 vols (Metz: Claude Lamort, Lausanne Durand l’aîné, 1792) MYLNE.707 (v.2)

Benedikte Naubert (1756-1819) was one of the first professional female authors in Germany. Although her work has been overlooked in literary history because of its ‘trivial’ associations – a pejorative term, particularly in German literary historiography –, she influenced writers such as Ann Radcliffe and Friedrich Schiller by establishing the secret tribunal novel (Vehmgerichtsroman). Hermann von Unna (‘Hermann of Unna’, 1788) was the first of two such novels, with the second, Alf von Dülmen, following in 1791. Recently her oeuvre has been recognised for its importance in the development of the historical novel and fairy tale as literary genres, as well as preparing the ground for the genre of Gothic fiction.

Hermann von Unna was one of the first German Gothic novels to be translated into English in 1794 and was adapted for the stage at Covent Garden in 1795, and a French dramatization was published in 1791, Le Tribunal Secret. Naubert draws on the German Vehmgericht (Vehmic courts) of the Middle Ages to explore in an intricate, episodic plot, the fears ignited by the French Revolution of secret tribunals and conspiracy theories. Although the Taylorian does not hold any German editions of Naubert’s Hermann von Unna, it does have French and English translations, including copies of the first three editions of Hermann von Unna in English, which all stem from the same anonymously published translation. The English translation erroneously ascribes the novel to a so-called Professor Kramer, an ill-chosen pseudonym since it was linked to Karl Gottlob Cramer, a writer known for adventure novels.

Charlotte von Stein

Neues Freiheitssystem oder die Verschwörung gegen die Liebe (‘New System of Freedom or the Conspiracy Against Love’, 1798), in Charlotte von Stein, Dramen, ed. Susanne Kord (Hildesheim: Olms, 1998) (facsimile) EP.667.A.10

Charlotte von Stein (1742-1827), a lady-in-waiting at the court of Weimar, has featured in literary history primarily in association with Goethe. She is variously considered his close friend, muse, and – in the more sensationalist readings – his lover. But she also wrote several dramas, only one of which, Die Zwey Emilien (The Two Emilies), was published during her lifetime. Of these dramas, the tragedy Dido has garnered critical attention because of its gently comic portrayal of Goethe.

The comedy Neues Freiheitssystem oder die Verschwörung gegen die Liebe (‘New System of Freedom or the Conspiracy Against Love’, 1798), which explores the social construction of gender, is an interesting example of editorial practices. It was first published by von Stein’s grandson Felix von Stein in 1867, but in an edited form that reduced the original five acts to four. The drama was re-published with further editorial amendments by Franz Ulbrich, who based his edition on the 1867 publication, rather than on the original text.

Charlotte von Stein’s dramas were re-published as part of the series Frühe Frauenliteratur in Deutschland (Early Women’s Writing in Germany) by the publishing house Olms. These editions feature facsimiles of the original or pre-existing versions of the texts. In this case, the version of Neues Freiheitssystem oder die Verschwörung gegen die Liebe follows the twentieth-century publication edited by Franz Ulbrich.

Catherine the Great

![Catherine the Great and others, Théâtre de l’Hermitage de Catherine II, impératrice de Russie, 2 vols (Paris: F. Buisson, Year 7 [1798]) VET.FR.II.B.1412 (v. 1)](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/taylorian/wp-content/uploads/sites/155/2017/09/Catherine-the-Great.jpg)

Catherine the Great and others, Théâtre de l’Hermitage de Catherine II, impératrice de Russie, 2 vols (Paris: F. Buisson, Year 7 [1798]) VET.FR.II.B.1412 (v. 1)

Elite women wrote and performed in private theatricals all across eighteenth-century Europe, from Elizabeth, Countess Harcourt, in Oxfordshire to Marie Antoinette at Versailles. Catherine the Great in Russia did not perform herself, but she wrote extensively for the public and the private stage. In 1787-1788, she led her courtiers and some foreign diplomats in composing a series of theatrical works (largely proverb plays), which were then performed by a troupe of French actors in the recently-built Hermitage theatre in her palace in St Petersburg. She oversaw the first edition of the plays in 1788, distributing the very small print run only to those who had contributed to the collection. One of the participants, the then French ambassador Louis Philippe de Ségur, then republished the work after her death. This volume is the curious result of publishing a relic of ancien régime culture in Revolutionary France: a particularly inaccurate engraving of the Empress faces a title page using the Revolutionary calendar but prominently crediting an absolute monarch and outspoken opponent of the Revolution as the lead author.

Beyond showcasing the variety of women’s writing in print form in the eighteenth century, one unique and valuable item that was on display was a letter by Joséphine de Beauharnais to Napoleon Bonaparte.

![Letter from Joséphine de Beauharnais to Napoleon Bonaparte, 5 Ventôse [24 February 1796] Courtesy of Bryan Ward-Perkins and the President and Fellows of Trinity College, Oxford](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/taylorian/wp-content/uploads/sites/155/2017/09/Josephine-Letter-Photo-1-1.jpg)

Letter from Joséphine de Beauharnais to Napoleon Bonaparte, 5 Ventôse [24 February 1796]. Courtesy of Bryan Ward-Perkins and the President and Fellows of Trinity College, Oxford.

There are few extant letters by Josephine known to exist, and this one in particular had been known to exist from an undated facsimile from the early nineteenth century. This original manuscript of the letter was discovered in the archives of Trinity College by the Fellow Archivist Bryan Ward-Perkins. Since the letter is rare, the manuscript was only exhibited for one day of the exhibition, replaced by a scanned paper copy for the remainder of the time. It was nonetheless quite the coup to be allowed to include the letter in the exhibition.

The exhibition ran in parallel with two conferences, originally ‘Women, Authorship, and Identity in the Long Eighteenth Century: New Methodologies’ and then extended to cover the Women in German Studies Open Conference on Reform and Revolt. The exhibition was not just of interest to university students and academics, however, since it was also shown to the school pupils on the UNIQ summer schools in German and French – in the hope of conveying to the next generation how exciting it can be to work with books and manuscripts as historical objects.

Joanna Raisbeck

Somerville College, University of Oxford