This blog post and book display for June is a showcase of the library’s excellent range of books on medieval Wales and Ireland. To limit the vast number of books on the subject, we have chosen a small selection on the following three themes: languages, literature and afterlives.

Languages

While Welsh and Irish are the obvious languages spoken in medieval Wales and Ireland, both cultures had many points of contact with other languages. After all, the precursor language to Welsh – British – was spoken in areas all across the island of Britain, not just where Wales is today, ranging from around southern Scotland right down to modern day Cornwall. This meant that, during the Roman rule of Britain and into the fifth century, many British speakers also spoke Latin. Some Latin loan-words still survive into today’s Welsh: for example, the word for ‘ship’ – llong – stems from the Latin navis longa. Thomas Charles-Edwards offers an excellent account of this mixing pot of languages in the early medieval period in chapters one and two of Wales and the Britons.

Ireland, by contrast, had a very different introduction to the Latin language. Ireland never came under the rule of the Roman Empire: thus, inhabitants of the island only began to learn Latin when they began to convert to Christianity, in order to read the vulgate Bible and celebrate the liturgy. Elva Johnston has carefully explored the tension between the use of the vernacular Irish language and Latin in Literacy and Identity in Early Medieval Ireland: for example, she places medieval Irish writing into context with continental rhetorical education, and explores the interdependence of literacy in the vernacular with literacy in Latin.

Interest in Latin was not solely linked to dealings with the Roman empire, nor to the Christian church. Two books in the Taylor’s collections exemplify Irish and Welsh authors’ complex engagement with texts and stories from classical antiquity. Brent Miles’ Heroic Saga and Classical Epic in Medieval Ireland explores how medieval Irish authors used classical epics as an interpretive lens or inspiration for their own vernacular literature. From a different angle, Paul Russell explores the engagement of medieval Welsh scribes and authors with one specific Roman author in his Reading Ovid in Medieval Wales.

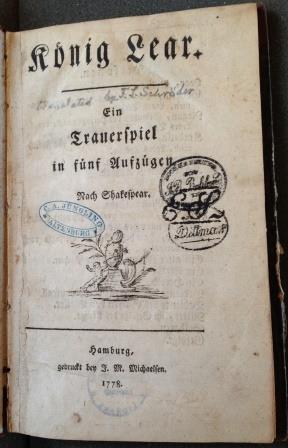

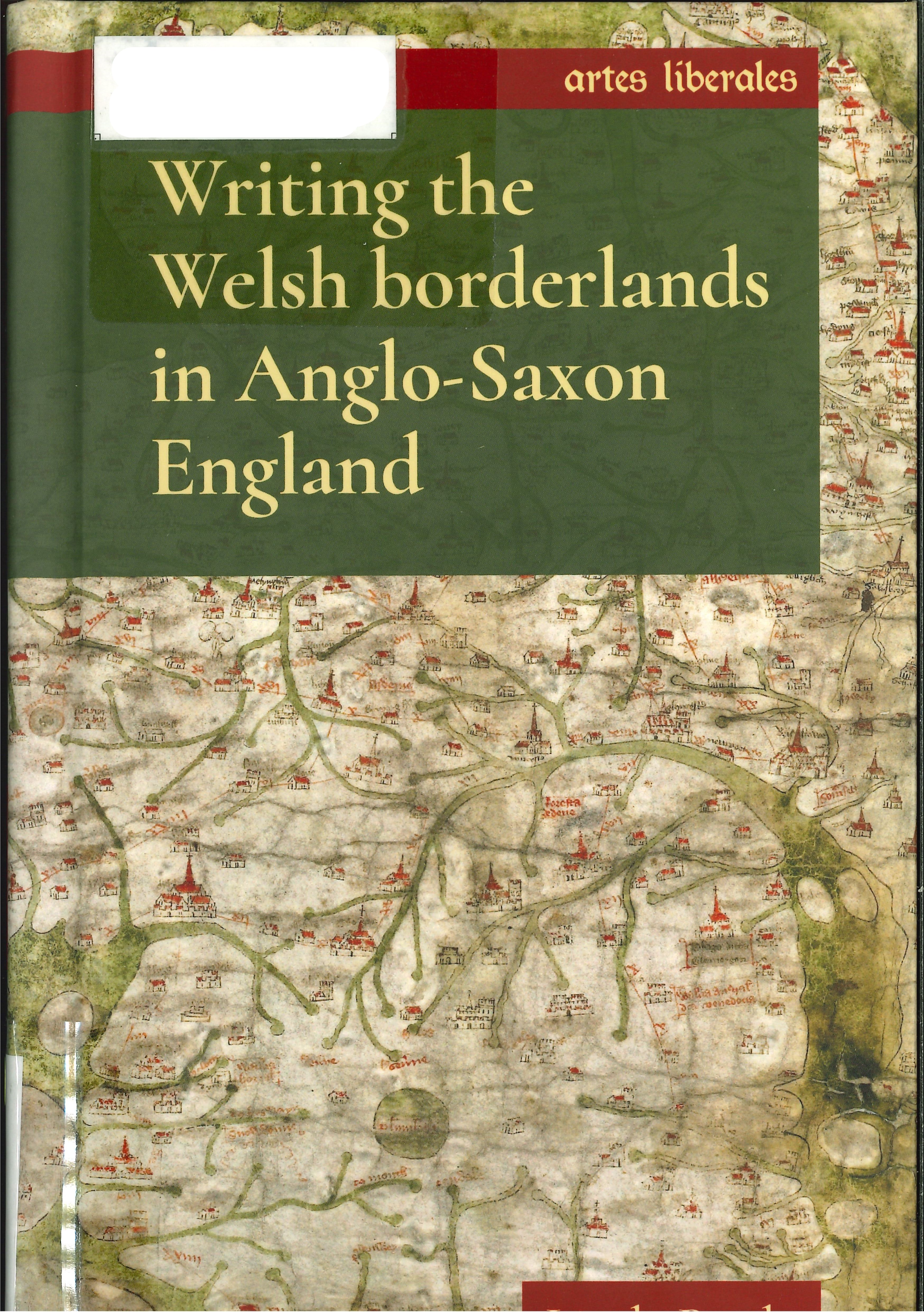

Beyond Latin, several other languages were spoken and understood in medieval Wales and Ireland. In this display, we have taken Wales as a particular example. Borders and frontiers became more pronounced between Welsh speakers and English speakers in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, as Welsh speakers had gradually become more confined to beyond the Severn river. While interactions between these groups are usually characterised as antagonistic, the first chapter of Lindy Brady’s Writing the Welsh borderlands in Anglo-Saxon England offers a more cooperative picture of this multi-lingual landscape. In it, she studies a charter drawn up by both Welsh and English speakers, who collaborated in order to tackle the problem of cattle theft in the eleventh century.

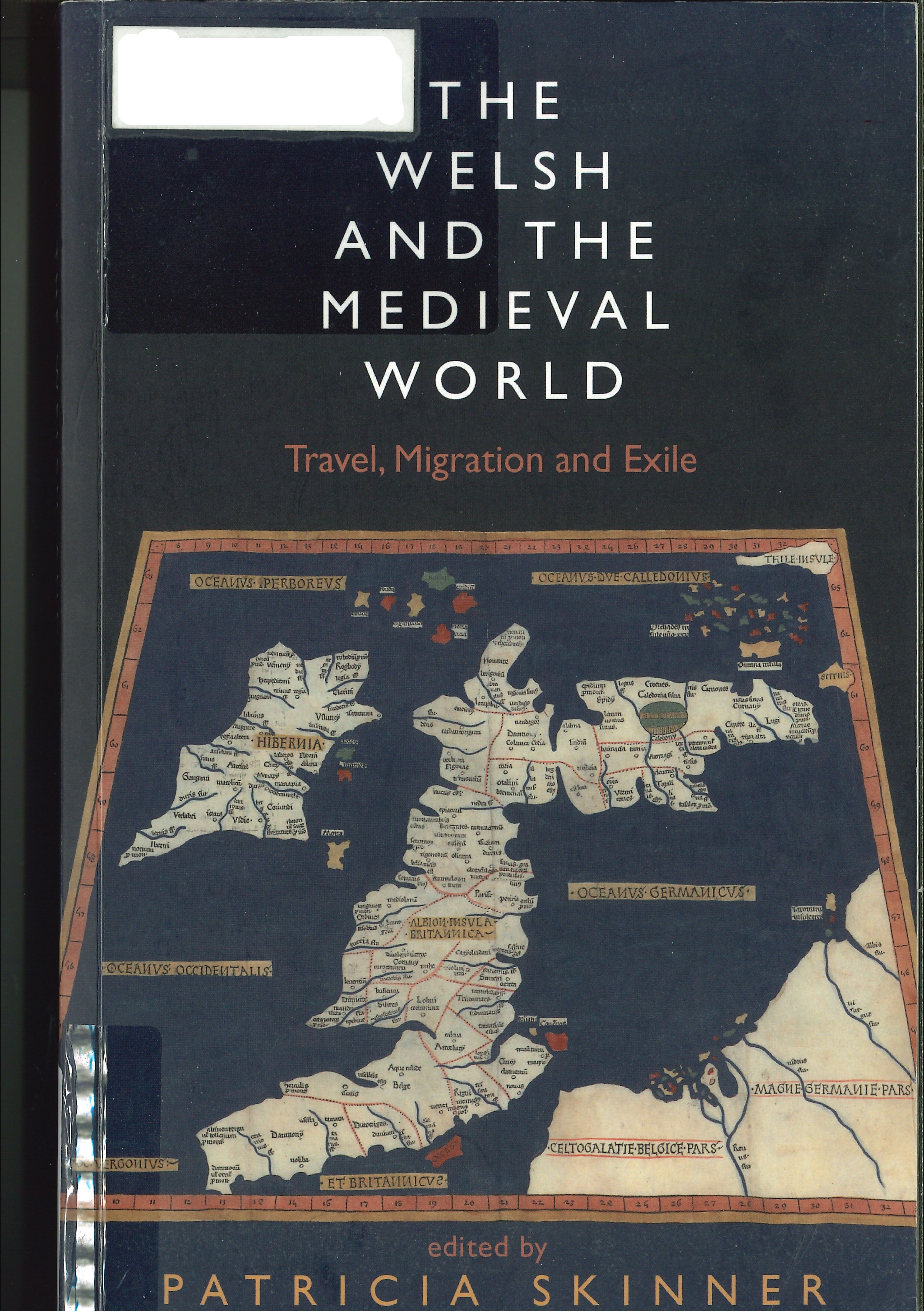

The collection of essays, The Welsh and the Medieval World: Travel Migration and Exile, offers a number of different angles onto medieval Wales’ connections to courts and peoples living across Europe. In particular, Gideon Brough’s chapter examines Welsh diplomacy with the French court in the medieval period, demonstrating that Welsh princes and military leaders were in direct contact with continental courts and kings, rather than being isolated from continental politics or using England as a sole intermediary.

Literature

A rich literary corpus has survived from both medieval Ireland and Wales, and the Taylor boasts a wide collection of editions and studies of such texts. For those not immediately familiar with literature from these cultures, you may nevertheless have heard of two particularly notable prose tales: the Irish Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley) and the Welsh Mabinogion. The Taylor holds several translations of both, but we have chosen one of each for this display. Thomas Kinsella’s edition is a classic version, with some beautiful ink illustrations by Louis Le Brocquy accompanying the text. Sioned Davies’s work is a translation of the eleven tales that make up the Welsh masterpiece known as the Mabinogion. Davies also includes a comprehensive introduction to medieval Welsh literature and the culture which gave rise to such stories in this book.

Some of the earliest poems in the Welsh language are preserved in monumental compilations, such as those in the Llyfr Taliesin (The Book of Taliesin). The poems in this manuscript have recently been translated and edited by Gwyneth Lewis and Rowan Williams in a beautiful edition for Penguin. You might have heard more about this particular collection of poems at this year’s O’Donnell Lecture, where Dr Rowan Williams spoke about ‘The Book of Taliesin: Welsh Identity and Poetic Identities’. Another very early Welsh poem is Y Gododdin (The Gododdin), a battle eulogy written by the early Welsh poet Aneirin. It has received a recent edition and translation by Gillian Clarke.

If you want to read beyond an edition of a text, the Taylor has copies of the most important studies of medieval Irish and Welsh literature. Ralph O’Connor’s The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel is a fantastic case-study in reading an Irish scél (saga or story), and provides an excellent foundation from which to read other such stories. Togail Bruidne Da Derga (earliest portion of the text written c. 1050-1100) concerns Conaire Mór, an Irish king who is doomed to contradict the increasingly impossible conditions of a curse (geis in Irish) laid upon him. This eventually results in his gruesome demise. Scholarly attention had previously focused on philological aspects of the text, or the sources standing behind it. By contrast, O’Connor advocates for reading Togail Bruidne as a literary creation in its own right, examining the structural coherence of the text as a whole.

Another study takes a more thematic approach to Irish literature: Mark Williams explores the literary portrayal of the remnants of Ireland’s pagan pantheon in Ireland’s Immortals: A History of the Gods of Irish Myth. Williams’ study is sweeping in its chronological range, and guides readers from the earliest original medieval Irish texts, through the late medieval and early modern period, and finishes by analysing their reworking of Irish deities in modern texts such as those by W. B. Yeats and James Joyce. If you have ever heard of some Irish divinities – like the dread war goddess, the Morrigan, or Mannanán mac Lir, the mysterious deity of the sea – but wanted to know more about how such figures actually appear in Irish literature, this is the book for you.

One of the most enigmatic texts connected to medieval Wales is the Latin De Gestis Britonum (On the Deeds of the Britons). It was written by Geoffrey of Monmouth (fl. early- to mid-twelfth century) at some point between 1123 and 1139. Geoffrey pretended that his work was a translation of a book he discovered in either Welsh or Breton into Latin. While Geoffrey drew upon some earlier works in medieval Latin or Welsh, scholars are now agreed that he creatively filled the gaps between such sources with his own fictional material. The De Gestis is credited with popularising the story of King Arthur across Europe: before Geoffrey, Arthur was only mentioned briefly in a handful of early medieval Welsh poems and texts, where he is presented as an idealised warrior figure. Geoffrey moulded this Welsh Arthur into a very different character, making him a king as well as a fierce military leader. To read more about Geoffrey’s text and the immense impact it had upon medieval European literature and beyond, you can read the excellent collection of essays in the Taylor’s copy of A Companion to Geoffrey of Monmouth, edited by Georgia Henley and Joshua Byron-Smith. The essays within range from the manuscript dissemination of the text, its connections to other Welsh and English historical writing, through to its reception in cultures as far spread from Iceland to Byzantium.

Afterlives

The languages and literature of medieval Wales and Ireland continued to capture the imagination of authors into the early modern period and beyond. One such fascinating, but poorly-read, author is Elis Gruffydd (c. 1490–c. 1552). Elis was born in Flintshire in Wales, but served as a soldier in the English army and eventually ended up living in the English garrison in Calais. What makes Elis unique is that he poured a vast amount of energy into writing his Chronicl y Wech Oesoedd (Chronicle of the Six Ages), an ambitious history of the world from its beginning to Elis’ own lifetime and one of the longest texts in the Welsh language. Elis’ eyewitness accounts in the second volume are particularly exciting, where he reveals an insider’s view of life in London under the Tudors, or life in the trenches as a soldier in Calais or across Europe. For example, he gleefully records gossip he heard from other Welsh speakers who worked as servants in Catherine of Aragon’s household. A rich tapestry of these stories has been translated this year by Patrick Ford, along with an excellent introduction to Elis’ life and times by Jerry Hunter, in Tales of Merlin, Arthur, and the magic arts: from the Welsh Chronicle of the six ages of the world.

Another important author from the Tudor period is John Prise. We encountered Geoffrey of Monmouth in the previous section of this blog post, but his influence continued well beyond the twelfth century. By the mid-1500s, many had begun to doubt the historical veracity of Geoffrey’s work. Yet, Prise enthusiastically believed in the events of the De Gestis, and produced the Historiae Britannicae Defensio (The Defence of the British History) in order to defend its contents. Prise’s Defensio saw some of the earliest analysis in print applied to medieval Welsh poetry: he quoted mentions of Arthur in such poems in an attempt to corroborate his historical existence (although, as we now know, Prise was sadly somewhat misguided). Prise was also the author of the earliest printed book in Welsh – Yny lhyvyr hwnn (In This Book). Ceri Davies offers an excellent biography of Prise in his edition of the Historiae Britannicae Defensio.

As we move further into the modern period, some readers were not content simply to peruse the canon of Irish and Welsh literature: they wished to add their own works to this corpus, and pretend that their creations were genuine medieval artifacts. The Taylor holds two excellent studies of such authors. First, a collection of essays edited by Geraint Jenkins – A Rattleskull Genius: The Many Faces of Iolo Morganwg – explores the life and works of Iolo Morganwg. He was most famous for founding the Welsh Eisteddfod, but he also forged a number of poems by Dafydd ap Gwilym, one of the most important medieval Welsh authors and a contemporary of Geoffrey Chaucer. Second, Fiona Stafford’s The Sublime Savage: A Study of James MacPherson and the Poems of Ossian delves further into the biography of the Scotsman James MacPherson, who claimed to find a corpus of poetry written by Fionn Mac Cumaill’s son, Ossian, which he had actually written himself. Fionn was an important figure in Irish and Scottish fianna literature: you may have heard of Fionn through his anglicised name, Finn MacCool, or Ossian spelled as Oisín. Both MacPherson and Morganwg were genuinely talented poets in their own right, but shared an irresistible draw to the authority of their medieval predecessors.

Finally, the Taylor holds a number of volumes showcasing the influence of medieval Welsh and Irish literature on modern literature. We have chosen two books to exemplify this: first, Dimitra Fimi has examined the legacy of such stories in Celtic myth in contemporary children’s fantasy. In a different vein to an academic study, Matthew Francis has creatively re-translated and re-written the Mabinogion in a 2017 publication for Faber & Faber.

There are many more books on medieval Welsh and Irish culture and literature in the basement of the Taylor. We hope this small selection will inspire you to explore it further, if you haven’t done so already.

Jenyth Evans, Reader Services Supervisor, Bodleian Art, Archaeology and Ancient World Library & DPhil Candidate, Faculty of English

With many thanks for additional bibliography and advice to Janet Foot, Celtic Subject Librarian, Taylor Institution Library

Bibliography

Aneirin. The Gododdin: Lament for the Fallen. Edited by Gillian Clarke, Faber & Faber, 2021.

Brady, Lindy. Writing the Welsh Borderlands in Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester University Press, 2017.

Charles-Edwards, Thomas. Wales and the Britons, 350-1064. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Davies, Sioned, editor. The Mabinogion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Fimi, Dimitra. Celtic Myth in Contemporary Children’s Fantasy: Idealization, Identity, Ideology. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Francis, Matthew. The Mabinogi. Faber & Faber, 2017.

Gruffydd, Elis. Tales of Merlin, Arthur, and the Magic Arts: From the Welsh Chronicle of the Six Ages of the World. Translated by Patrick K. Ford, introduction by Jerry Hunter, University of California Press, 2023.

Henley, Georgia, and Joshua Byron Smith, editors. A Companion to Geoffrey of Monmouth. Brill, 2020.

Jenkins, Geraint H., editor. A Rattleskull Genius: The Many Faces of Iolo Morganwg. University of Wales Press, 2005.

Johnston, Elva. Literacy and Identity in Early Medieval Ireland. Boydell & Brewer, 2013.

Kinsella, Thomas. The Táin. Illustrated by Louis Le Brocquy. Oxford University Press, 1970.

Lewis, Gwyneth, and Rowan Williams, translators. The Book of Taliesin: Poems of Warfare and Praise in an Enchanted Britain. Penguin Classics, 2019.

Miles, Brent. Heroic Saga and Classical Epic in Medieval Ireland. Boydell and Brewer Limited, 2012.

O’Connor, Ralph. The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel: Kingship and Narrative Artistry in a Mediaeval Irish Saga. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Prise, John. Historiae Britannicae Defensio: A Defence of the British History. Edited by Ceri Davies, Bodleian Library, 2015.

Russell, Paul. Reading Ovid in Medieval Wales. Ohio State University Press, 2017.

Skinner, Patricia. The Welsh and the Medieval World: Travel, Migration and Exile. University of Wales Press, 2018.

Stafford, Fiona J. The Sublime Savage: A Study of James MacPherson and the Poems of Ossian. Edinburgh University Press, 1988.

Williams, Mark. Ireland’s Immortals: A History of the Gods of Irish Myth. Princeton University Press, 2016.

![Catherine the Great and others, Théâtre de l’Hermitage de Catherine II, impératrice de Russie, 2 vols (Paris: F. Buisson, Year 7 [1798]) VET.FR.II.B.1412 (v. 1)](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/taylorian/wp-content/uploads/sites/155/2017/09/Catherine-the-Great.jpg)

![Letter from Joséphine de Beauharnais to Napoleon Bonaparte, 5 Ventôse [24 February 1796] Courtesy of Bryan Ward-Perkins and the President and Fellows of Trinity College, Oxford](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/taylorian/wp-content/uploads/sites/155/2017/09/Josephine-Letter-Photo-1-1.jpg)

![Luther, Martin. Ein Wellische Lügenschrifft/ von Doctoris Martini Luthers Todt/ zů Rom außgangen. Papa quid ægroto sua fata ... perfide Papa velis. Nürnberg: [Hans Guldenmund], 1545.](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/taylorian/wp-content/uploads/sites/155/2017/02/multilingual-layouts3.jpg)