Society for Italian Studies Biennial Conference

Society for Italian Studies Biennial Conference

Oxford, Taylor Institution,

25-28 September 2015

Before the rush of new students and returning students, the Taylor Institution opened its doors to 200-plus delegates, over three days, for the Biennial Conference of the Society for Italian Studies, 2015. (Link here to the SIS-Biennial-Conference-Programme.)

2015 has been an auspicious year for big anniversaries in Italian culture, including: 750 years since the birth of Dante Alighieri, 500 since the death of Venetian printer Aldus Manutius, 30 since Italo Calvino’s death, and 100 since Italy revoked the Triple Alliance (with Germany and Austria-Hungary) and entered World War I on the side of the Triple Entente (France, Great Britain and Russia). We also lie on the eve of the anniversary of the first edition of Ariosto’s epochal epic, the Orlando Furioso. The conference programme, together with the display of items from the Taylor Institution Library’s Special Collections as well as the Sackler Library’s Wind Room, reflected the ongoing cultural impact of these figures and events. (Link here to the SIS-2015-Display-List.)

Throughout 2015, Dante’s 750th birthday has been celebrated by popes and politicians, with readings, concerts and conferences and, thanks in part to the 1939 deposit of the Moore Collection by The Queen’s College with the Taylorian, a number of early print editions of Dante’s Commedia were on view.

- Mapping the Inferno, 1: Antonio Manetti, Dialogo [. . .] circa al sito, forma, et misure dello Inferno di Dante Alighieri (Florence: Giunta, 1506)

- Mapping the Inferno, 2: Dante, Commedia (Venice: Aldus Manutius, 1515)

Each item shown was intriguing for different reasons, not least for allowing us to focus on the material culture and circulation of Dante’s texts during the transition from manuscript to print. An interest in these questions, the so-called ‘material turn’ in some branches of research, was also evident in a number of SIS conference panels considering the content and afterlives of Dante’s texts.

- Dante, Commedia (Venice: Bartolomeo de Zanni da Portese, 1507)

- Dante, Commedia (Venice: Iacob del Burgofranco, 1529)

- Dante, Commedia (Venice: Giovambattista & Melchior Sessa, 1564)

Striking images from various editions of Dante’s Commedia were on display, such as in a 1507 Venetian edition, which included illustrations based on Botticelli’s treatment of the poem. One Commedia shown (Venice, 1529), bore images of classical poets in parallel with Italy’s Tre Corone, Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio.

The display of this 1529 edition, with its Tre Corone array, of was of broader relevance in a year which, as well as marking a significant anniversary of Dante’s birth, saw the publication of the new Cambridge Companion to Boccaccio, presented in a special ‘unroundtable’ conference session by its editors, Rhiannon Daniels and Guyda Armstrong. This session served not only to present a complex and fascinating author, but also to consider the role of medieval and early modern specialists in the wider scope of Italian and modern language departments, in the humanities, and in the public sphere, picking up discussions in other venues such as the recent International Medieval Congresses at Leeds and Kalamazoo.

Not to be left out, Petrarch will also shortly be receiving his own Companion volume in the Cambridge series, so that the three big guns of the medieval canon will, at last, be equally well-served in terms of introductory criticism. Students of medieval Italian (Oxford Italianists taking Paper VI) have never had it so good!

During his sadly curtailed life-time, Italo Calvino (1923-1985) produced a body of work that remains a staple of undergraduate curricula, of graduate and professional research agendas (turning up in a SIS conference panel on experimental narratives), and (in the original Italian and in translations into numerous languages) of bookshop shelves around the world. In Calvino’s fiction, non-fiction, lectures, screen-plays, essays, and articles exist strands with always at least half an eye on Italian literary and narrative traditions, from fairytales to ‘classics’ of literature. This interest is reflected in Calvino’s edition of his oft-proclaimed favourite text, Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, of which a 1555 and 1570 edition were shown. In addition, a vinyl recording curated by Calvino was displayed alongside the first critical edition of the 1516 edition of the text (by Oxford scholar Marco Dorigatti).

- Ariosto, Orlando Furioso (Venice: Gabriele Giolito, 1555)

- Orlando Furioso di messer Ludovico Ariosto. Ed by Italo Calvino (Fonit Cetra, 1967): Cover of LP box set

The Furioso, its editions and afterlives also had a marked presence in a variety of panels over the course of the SIS conference. The 1570 edition of Ariosto’s text on dislay was of particular interest not so much for what had been included, but for what one reader had attempted to delete.

- Ludovico Ariosto, Orlando Furioso (Lyon: Guillaume Rouillé, 1570)o

Lines describing discordant and unseemly behaviour among friars (Canto 27.37) have been struck through in an act of censorious literary disagreement. This somewhat drastic intervention again brings the material fates of the texts we study into sharp relief.

As well as celebrating the lives and works of figures like Dante, Calvino, and Ariosto, recent years have also marked more sombre recollections relating to the beginning of the Great War, declared on 28 July 1914, and joined by Italy, after the collapse of its Triple Alliance with Germany and Austro-Hungary, on 23 May 1915.

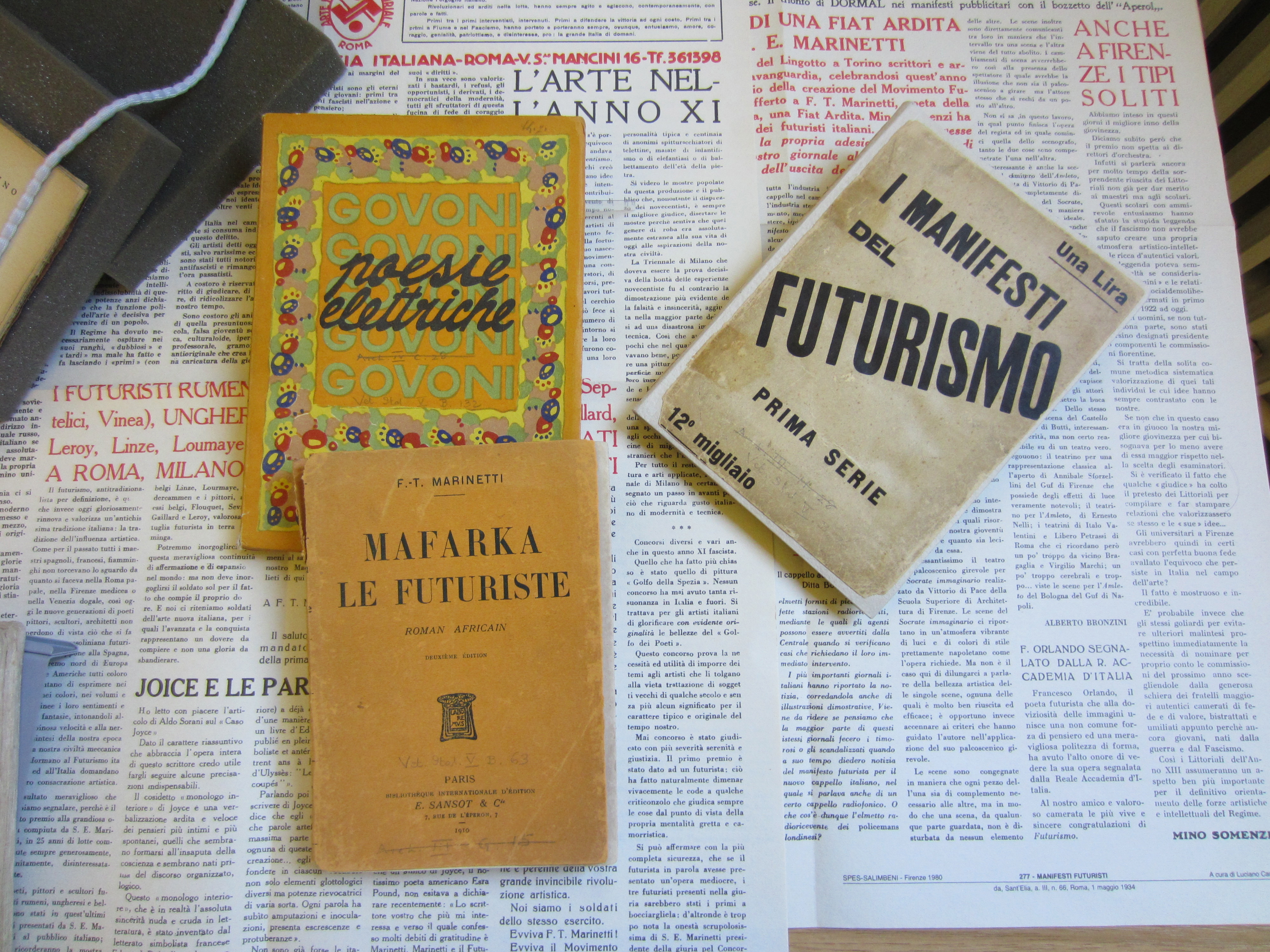

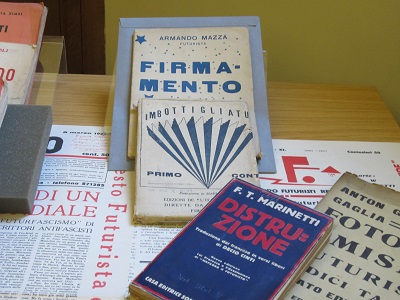

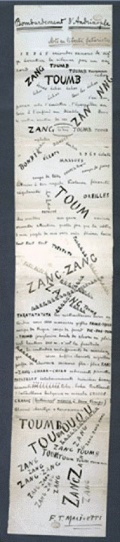

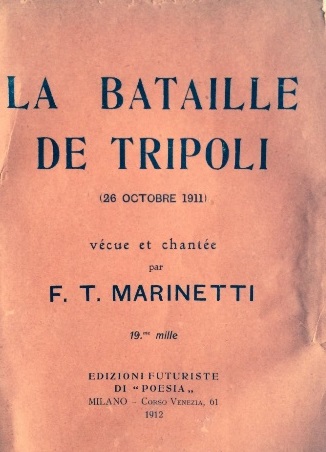

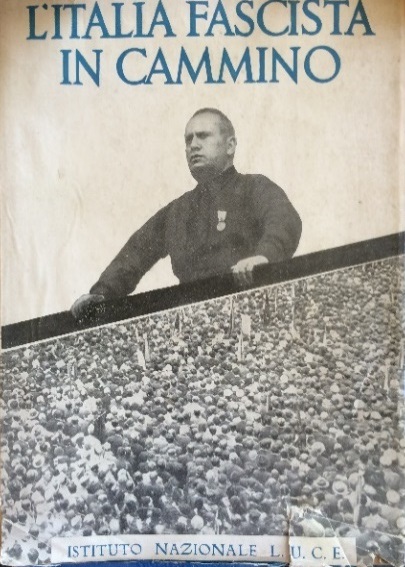

- Views of the Futurism and Fascism Display Case

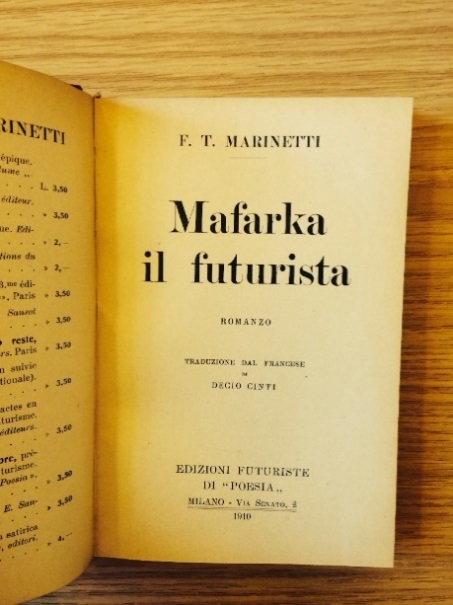

While these remembrances have largely focused on loss and sacrifice, the Italian Futurists thought World War I was great in a rather different sense, celebrating warfare as ‘the world’s only hygiene’, to use F.T. Marinetti’s phrase in his Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909). A copy of this text was included among a visually striking display of his works, along with texts by his contemporaries and co-conspirators. (See also the Taylorian’s blog posting Futurism, Fascism and the Art of War.)

This Manifesto was one of several texts featuring in the final SIS keynote, by Robert Gordon, exploring the developing role of chance and luck in ‘modernist’ Italian works.

Indeed, the exhibition provided a visual counterpart to all three keynotes. Zygmnut Barański’s address ‘On Dante’s Trail’, was very concerned with the use of archival materials in relation to ‘historically inflected research’ on Dante; Lina Bolzoni’s talk focused on the perils and pleasures of reading and the importance of texts by great authors to the construction of the self in early modern Italy; and the aforementioned Futurist and modern publications on show reflected the heart of Robert Gordon’s discussion.

See also:

Guyda Armstrong, Rhiannon Daniels and Stephen J. Milner, eds. The Cambridge companion to Boccaccio (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2015)

Zygmunt G. Barański and Martin McLaughlin, eds. Italy’s three crowns: reading Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio (Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2007)

Rachel Jacoff, ed. The Cambridge companion to Dante (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1993)

M. McLaughlin Italo Calvino (Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 1998)