The Image of Dante, the Divine Comedy and the Visual Arts

in the Ashmolean Museum and the Taylor Institution Library

I: The Image of the Poet

Oxford’s dedication to Dante is deep-rooted. The University’s Dante Society was set up in 1876 (thirteen years before the foundation of the Dante Alighieri Society in Italy), and has provided a focus for the reading and discussion of his work ever since. The intellectual preoccupation has been overwhelmingly literary and textual. Yet the cult has had more extensive visual dimensions than its devotees may have realised (or wished to acknowledge). Oxford bears rich traces of this visual culture.

Earlier this year, the Ashmolean Museum’s Print Room hosted two seminars — one for the University’s Dante Society, the other for the Print Research Seminar — at which works in the collections of the Ashmolean and the Taylor Institution Library were presented and discussed. This is the first of two short pieces deriving from those seminars. Both posts focus on the iconography of Dante, as this is represented in particular in the collections of the Ashmolean Museum and of the Taylor Institution Library in Oxford. The second piece (to be posted later in the year) will consider illustrations to the Divine Comedy between the sixteenth and the twenty-first century. This, the first post, addresses the image of Dante.

Reception of Dante has always been inflected by perception of the poet. Each age, just as it re-reads the Comedy, at the same time re-envisions its author. Readers always believe they know what Dante looked like – a remarkable claim to authentic connection, considering how little information we really have. The Ashmolean possesses a plaster mould of what in the nineteenth century was reputed to be ‘Dante’s death-mask’.

Mask of Dante. Plaster, 19th century (Ashmolean Museum: WA.OA1767 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

This example was given in 1879 to the Oxford Dante Society by Seymour Kirkup, a fanatical Dantophile and long-standing resident of Florence (who believed he was in direct spirit communication with the great poet). The minutes of the Dante Society in November of that year record the gift:

Baron Kirkup having at the suggestion of Signor de Tivoli kindly presented to the Society a Cast from the Mask of Dante in his possession, which formerly belonged to Signor Bartolini [Lorenzo Bartolini (d.1850), sculptor and maker of casts in Florence], and which has been on good grounds believed to have been taken from the Mask originally placed upon Dante’s Tomb at Ravenna. Resolved that the best thanks of the Society be conveyed to Baron Kirkup [via] Signor de Tivoli. Signor de Tivoli informed the Society that it was also the wish of Baron Kirkup that in the event of the Society being at any future time dissolved the cast should remain in the possession of the Secretary for the time being, or other chief officer of the Society.

In the event, however, the head was in 1920 consigned by the Society to the Ashmolean Museum, where it has been little noticed.

The head, which was made in two halves, may have been created from the plaster head of Dante kept in the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, which had formerly belonged to Kirkup. (This is the head around which revolves the plot of the book, Inferno, published in 2013 by Dan Brown.) Kirkup had also, in 1840, employed a restorer to look for the supposed Portrait of Dante by Giotto in the chapel of the Bargello, of which he produced a tracing and drawing, on the basis of which a chromolithograph was published by the Arundel Society in the following year.

Portrait of Dante after the image in the Bargello, published by the Arundel Society, 1841 (© The British Museum)

In reality the fresco in the Bargello dates from after Giotto’s death, and is not likely to represent Dante. The Palazzo Vecchio head, and another in the Florentine Palazzo Torrigiani del Nero, were thought in the nineteenth century to be based either upon a death-mask or upon another three-dimensional image created for the poet’s tomb at Ravenna in 1483. None of this has any basis in historical fact. The stories tell us, in despite of the absence of evidence, about a recurrent desire for proximity to the poet through his supposed likeness.

The history of Dante’s portrait took a new turn in 1865 when, in the six-hundredth anniversary of his birth and in the highly relevant context of the Unification of Italy, his bones (seemingly authentic) were rediscovered near to the tomb in Ravenna. The availability of the skull (albeit lacking the jawbone) led – after some time and strong official resistance to any interference with the sacred relics – to attempts to reconstruct Dante’s facial appearance on this basis. This has continued to generate versions which have made their own respective contemporary claims to the Dante aura. That produced in the 1930s by Fabio Frassetto was framed in the political language of the time, and was claimed to prove (against other theories) that Dante was ‘of the Mediterranean race’.

![Fabio Frassetto, Head of Dante, bronze (From: A.Cottignoli and G.Gruppioni, Fabio Frassetto e l’enigma del volto di Dante (2012])](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/taylorian/wp-content/uploads/sites/155/2017/11/Image03-FrassettoDante.jpg)

Fabio Frassetto, Head of Dante, bronze (From: A.Cottignoli and G.Gruppioni, Fabio Frassetto e l’enigma del volto di Dante (2012])

In 2006 anthropologists at the University of Bologna, working on the skull with new methods of facial reconstruction, came up with what La Repubblica announced on its front page to be, at last, ‘the true portrait of Dante’.

The only relatively early verbal description of Dante, which can be set alongside this reconstruction, is that given by Boccaccio, presumably based on conversations held in Ravenna with people who had known the poet in his fifties:

“Our poet was of middle height and in his later years he walked somewhat bent over, with a grave and gentle gait. He was clad always in the most seemly attire, such as befitted his ripe years. His face was long, his nose aquiline, and his eyes rather big than small. His jaws were large, and his lower lip protruded. His complexion was dark, his hair and beard thick, black and curly, and his expression ever melancholy and thoughtful.”

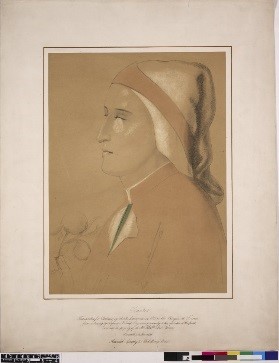

What, meanwhile, have remained more plausible (if less ‘scientifically’ authenticated) portraits of Dante were those made at the beginning of the sixteenth century by Raphael, as part of his decoration for the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican Palace. Raphael had seen in Florence a number of fifteenth-century depictions of Dante which had together established a more-or-less canonical image: these must lie behind his depictions. Dante appears in Raphael’s frescoes among the theologians witnessing the Disputa concerning the Holy Sacrament, and again as one of the poets joining Apollo on Parnassus. Later artists would copy these representations of the poet, especially the former, which is closer to the eye level of the visitor. The Ashmolean owns a fine black chalk drawing after the Dante of the Disputa which may have been made by a pupil of Thomas Lawrence (but not, pace Francis Douce who owned the drawing before giving it to the museum, by Lawrence himself, who only visited Rome late in life and when working in a different style).

Pupil of Thomas Lawrence(?), Dante, after Raphael (Ashmolean Museum: WA1863.1413 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

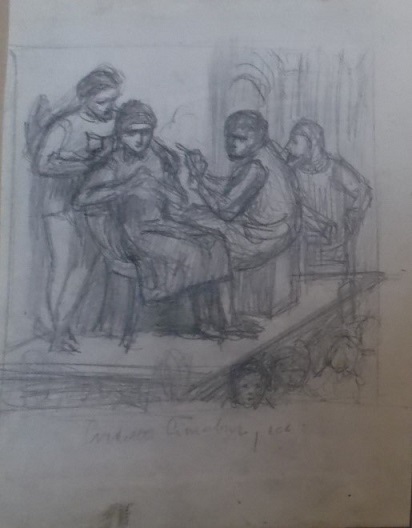

The nineteenth century would see a shift in taste from this type of the Dante portrait, haughty and austere, to a focus on a more youthful and romantic image. The change was facilitated by the publication of the Bargello ‘portrait’. It was the presentation to his father (by the indefatigable Kirkup) of a copy of this image which kindled in the young Dante Gabriel Rossetti an interest in the supposed relationship between Dante and Giotto, and fostered his own commitment to become an artist. The Ashmolean has relatively recently acquired a drawing for Rossetti’s painting of Giotto Painting Dante.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Giotto Painting the Portrait of Dante (record photo) (Ashmolean Museum: WA2014.36 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

Another drawing for the work is in the Tate and the finished painting (c. 1852) is in the collection of Andrew Lloyd Webber.

The importance to Rossetti of this image of friendship between the poet after whom he had himself been named and the ideal painter is indicated by the fact that he made a watercolour copy in 1859 (Fogg Art Museum), in which his own features were given to the figure of Giotto – a further creative dimension of the nineteenth-century Dante cult.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Giotto Painting the Portrait of Dante (Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop © President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Professor Gervase Rosser

History of Art Department & Faculty of History

University of Oxford