The Testimonio (Testimonial Literature)

Part I of this series of blog posts introduced the Robert Pring-Mill collection at the Taylor Institution Library and explored Nicaraguan poetry. The second part focused on serial publications, pamphlets and grey literature. Last but not least, Part III discusses the genre known as testimonial literature.

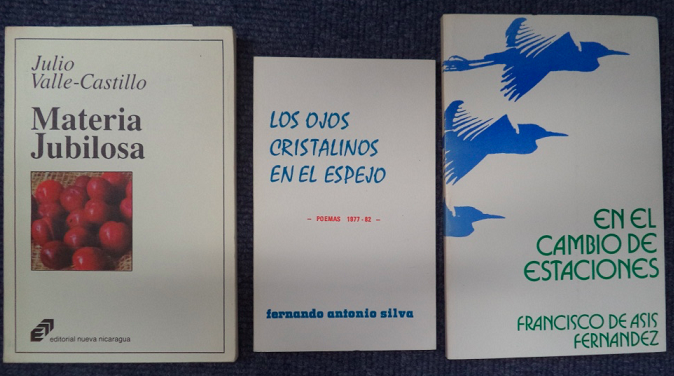

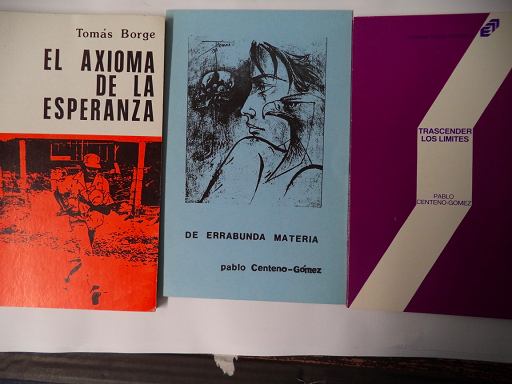

The Pring-Mill collection includes some very interesting books documenting the trajectory of the revolution from its early beginnings. A recurring form found in Latin American literature of that time, the testimonio flourished in Nicaragua during the course of the revolution and was developed, according to Beverley and Zimmermann (1990), by the American feminist and academic Margaret Randall in her various publications. Randall lived for many years in Nicaragua and published her well-known book Sandino’s Daughters, the story of the women who fought in the revolution, in 1981. Also in the Pring-Mill collection is her book Risking a Somersault in the Air: Conversations with Nicaraguan Writers (1984), comprising 12 interviews with some of Nicaragua’s most important writers/revolutionaries. Randall also wrote the introduction and transcribed the story of Doris Tijerino in Doris Tijerino: Inside the Nicaraguan Revolution (1978), which tells the story of one woman’s life, shaped by the country’s struggle, as an illustration of women’s experiences everywhere in times of tyranny and war. Cristianos en la Revolución (1983) comprises Randall’s interviews with some of the most important figures in the new revolutionary government, some of whom were also integrating liberation theology with the Nicaraguan movement: Ernesto Cardenal, the then Minister of Culture; Uriel Molina, director of the religious centre Antonio Valdivieso; and Luis Carrión, Commander of the Revolution and Deputy Minister of the Interior.

Barricada: Corresponsales de Guerra (1983) was a newspaper launched during the insurgency period as a means to counter the government-owned media and it became the official organ of the FSLN. It is a journalistic account of five war testimonials of events between March and June 1983 by a group of war correspondents who take up arms. It includes photographs in black and white of the involvement of these war correspondents in their first experience of war and how they bonded with other Sandinista militias while following them into combat.

In the tradition of Bartolome de las Casas’ Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias (Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, 1552), priest Teófilo Cabestrero published Nicaragua: Crónica de una sangre inocente (1985), an account of 60 civilian testimonials as victims of atrocities and crimes in Nicaragua at that time. It describes how the peasant population of Latin America was the primary victim of the violent social, economic and political struggles.

Published by the new revolutionary publisher Nueva Nicaragua, Sandino: Enfrenta al imperialismo (1981) is a large, beautiful collection of black and white photographs drawn from Nicaraguan citizens’ photographs taken during the revolutionary struggle led by Augusto Sandino (1927-1933). This book was published for the 47th anniversary of the death of Augusto Sandino (1934) by the Junta de Gobierno de Reconstrucción Nacional. Divided into nine parts, it documents the main players of the time and their movements, including Sandino’s travels through Mexico.

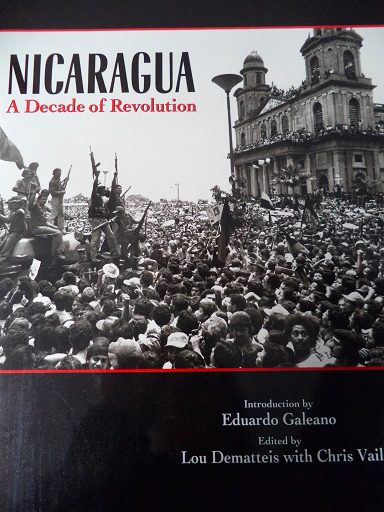

Another large book of black and white photographs is Nicaragua: A Decade of Revolution (1991) with an introduction by Eduardo Galeano and edited by Lou Dematteis with Chris Vail. It is a chronology of snapshots of Nicaragua from 1979, the year of the overthrow of dictator Anastasio Somoza, until 1990, the year of the election victory of Violeta Chamorro. These photographs offer a brutal but realistic documentation of the triumphs and tragedies of these years.

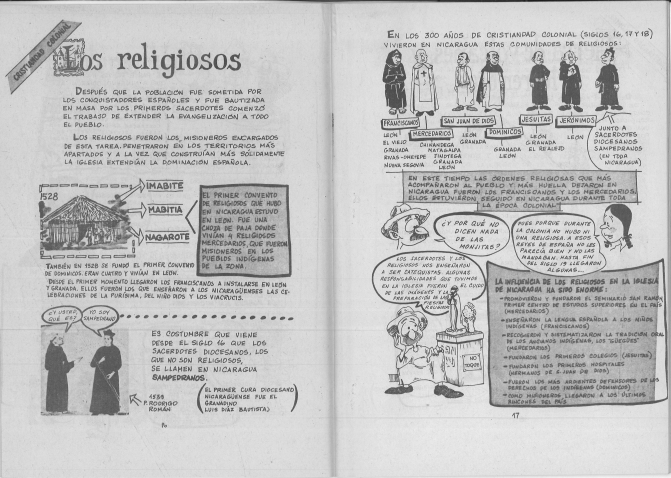

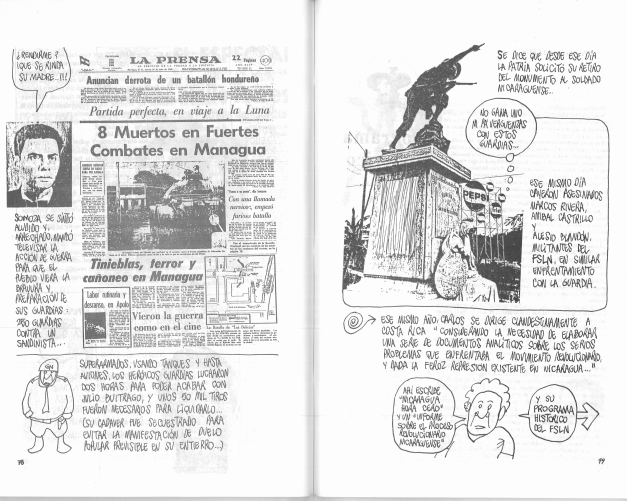

The Pring-Mill collection contains other publications documenting, through photography, Nicaragua during different periods and through different lenses, as well as many other books, magazines, journals and grey literature — too many to describe here but which are definitely worth further investigation. One of my favourites is the book Carlos Para Todos (1987). A biography of Carlos Fonseca and history of Nicaragua from 1936 onwards, it is illustrated, in comic-book style, by the illustrator and political cartoonist Eduardo del Rio, known by his pen name Rius.

Readers may know him as the author of the very popular book Marx For Beginners which started the For Beginners series. Employing his characteristic style and satire he gives a short and simple narrative of Nicaragua from 1936, the year in which the Nicaraguan teacher and librarian Carlos Fonseca, founder of the FSLN, was born. The book tells Fonseca’s story with help of comic-book illustrations, photographs, and articles in an anarchic and accessible style.

Readers may know him as the author of the very popular book Marx For Beginners which started the For Beginners series. Employing his characteristic style and satire he gives a short and simple narrative of Nicaragua from 1936, the year in which the Nicaraguan teacher and librarian Carlos Fonseca, founder of the FSLN, was born. The book tells Fonseca’s story with help of comic-book illustrations, photographs, and articles in an anarchic and accessible style.

I am very grateful to Joanne Edwards and Frank Egerton for giving me the possibility to freely explore this collection and learn so much about a country that is seldom in the mainstream media and yet whose influence on Latin American literature and identity, in terms of its committed poetry and also its liberation theology, has been so powerful.

Natalia Bermúdez Qvortrup

University College of Oslo and Akershus

Intern, Social Science Library, Bodleian Libraries

Further reading

Arellano, Jorge Eduardo (1997) Literatura Nicaraguense Managua: Ediciones Distribuidora Cultural

Beverley, John and Marc Zimmerman (1990) Literature and Politics in the Central American Revolutions. Austin: University of Texas.

Forster, Merlin H. and K.David Jackson (1990) Vanguardism in Latin American Literature: An annotated Bibliographical Guide. New York: Greenwood Press

Pring-Mill, Robert (1970) “Both in Sorrow and in Anger: Spanish American protest poetry” Cambridge Review vol. 91/2195.

Websites:

Cerezo Barredo: http://www.minocerezo.it/

For Beginners Books – About us: http://www.forbeginnersbooks.com/aboutus.html