‘Dostoevsky’s dead,’ said the citizeness, but somehow not very confidently.

‘I protest!’ Behemoth exclaimed hotly. ‘Dostoevsky is immortal!’

― Mikhail Bulgakov, The Master and Margarita

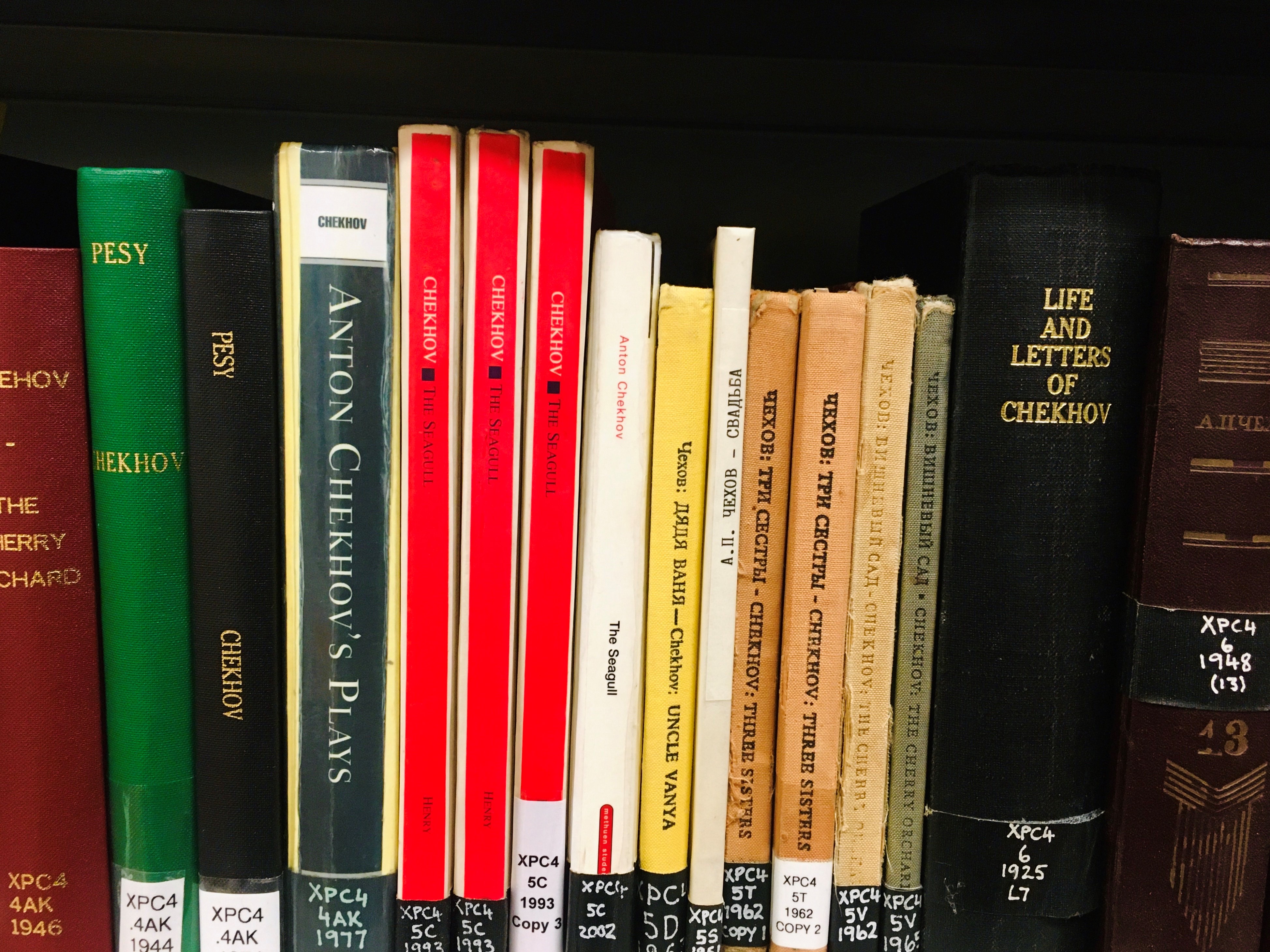

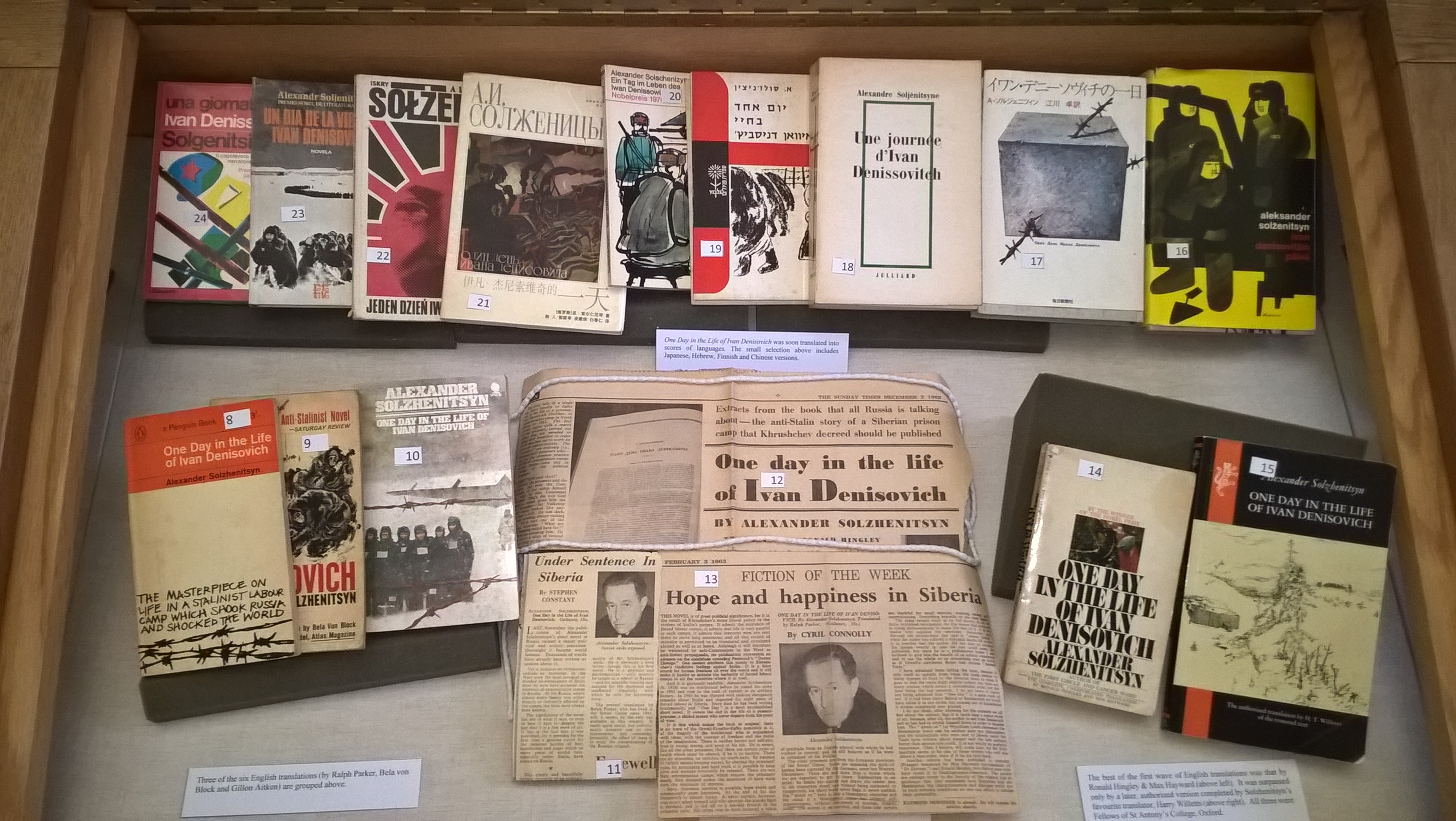

There is no prerequisite to know Russian if you work at the Taylor. The Slavonic collections returned to our St Giles’ location only three years ago from their home in Wellington Square, the newest layer to our nesting-doll of a library. We even have a cheat sheet for staff to navigate the Cyrillic alphabet, lest they be asked about a book they cannot read.

And yet somehow Russian—the language, the literature, the culture—permeates the building like a foundational block, the missing sister to the European languages carved as goddesses on our Eastern façade. Cyrillic, learned or cheated, is part of our daily rhythm.

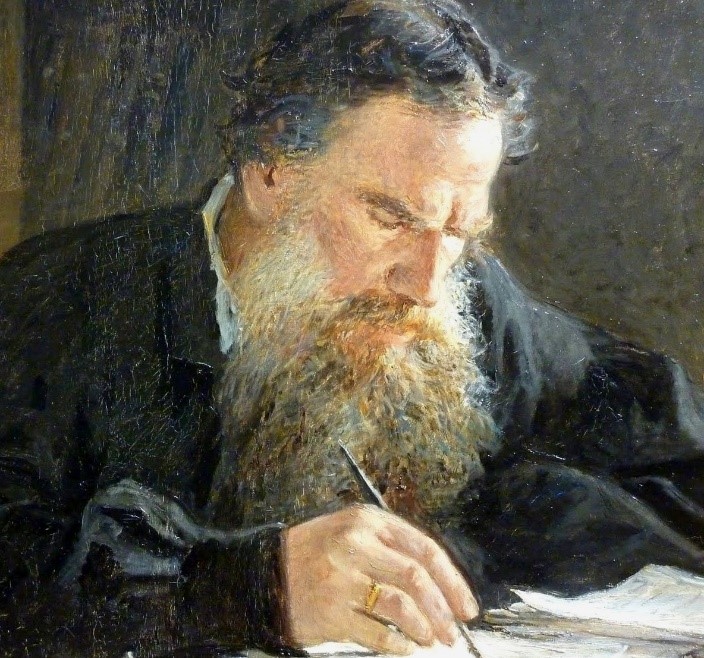

After two years working in the Taylor and seeing some mention of Tolstoy or Dostoevsky on a daily basis, I decided it was time to fill the gap in my education and read some of the classics. I started with Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina in Hilary term and spent Trinity term and the summer holiday reading Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov.

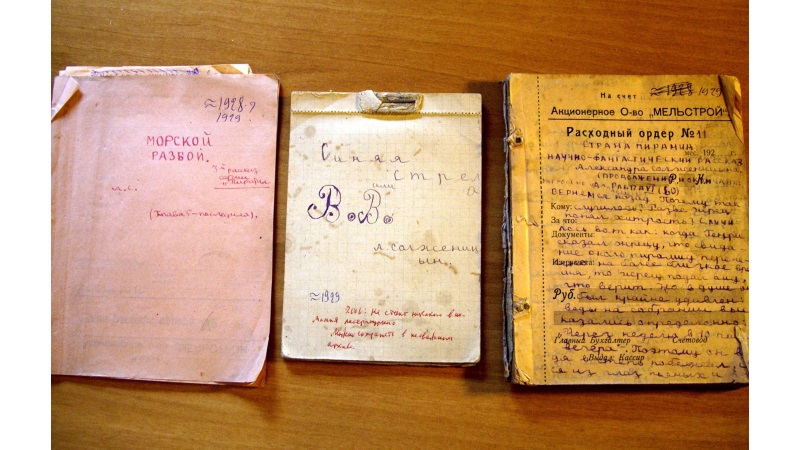

- Some of our most popular loans

- Some of our most popular loans

“Every person is either a Tolstoy person or a Dostoevsky

person,” one of my colleagues told me as

we discussed my progress.

“Well, which are you?” I asked.

“Oh, Tolstoy,” she said firmly.

Another colleague passed by—Nick, our Russian subject librarian.

“How about you?” I asked him. “Tolstoy or Dostoevsky?”

He paused. “Oh, that’s a hard one. But I have to go with Dostoevsky.”

We asked another colleague later—

Trevor, who studied Russian and French as an undergraduate before pursuing a career in libraries.

“Tolstoy,” he answered, nodding enthusiastically.

One by one, we asked the rest of our staff the ultimate Russian literature desert island question: if you had to choose, would you read Tolstoy or Dostoevsky?

The results:

Tolstoy: 9

Dostoevsky: 6

Neither: 2

Abstain: 3

Interestingly, the results are reflected in our collection: we hold 1131 books related to Tolstoy and 986 to Dostoevsky, almost the same ratio. Why, then, the preference for Tolstoy?

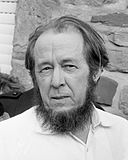

His visual language appeals to many of us who find reading Tolstoy like watching a movie, the scenes of Natasha’s dance or Anna’s descent a vivid picture that lingers long after reading. Dostoevsky, in contrast, sends us deep into the human psyche in works that read almost like plays, with harrowing insight into fundamental truths. That depth, though engendering strong loyalty from those who choose him, is daunting for others.

I spoke to one of my Russian colleagues to see how she felt about these two pillars of her national canon.

“For us [Russians], these people are like monuments like Lenin,” she explained. Reading them, especially Dostoevsky, draws her back to a childhood spent playing on snowy streets in the dark Russian winter.

So whom does she choose?

“Chekhov,” she answered after deliberating for a while, preferring his shorter form, lively language, and humour.

As for me? I find myself in the majority camp choosing Tolstoy, drawn in by the empathetic way he writes women and the sweeping scale of his stories. I must admit, however, that I think of The Grand Inquisitor and Ivan’s conversation with the Devil more than any individual Tolstoy scene.

We would love to know what our readers think about this battle of the greats. Let us know on our Facebook poll!

—————————————

Alexandra Zaleski

Taylor Institution Library