from Martha Repp

The eighth and last in the 2012 series of the Oxford Seminars on the History of the Book, convened by Professor I.W.F. Maclean, was held at All Souls College, Oxford on 9 March, 2012.

Ms. Susanna Berger, Kathleen Bourne Junior Research Fellow in History of Art and French at St. Anne’s College, Oxford, spoke on “Early modern French and Italian illustrated philosophical thesis prints and broadsides”. Ms. Berger’s paper focused on the philosophical broadsides and thesis prints produced in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. These prints are single-sheet publications, combining text and images to illustrate a particular aspect of philosophy, and they provide a fascinating insight, both from a theoretical and from a practical point of view, into how philosophy was taught in universities at this time.

In general terms, the philosophical ideas presented in these prints follow fairly closely the scholastic/Aristotelian approach to philosophy adopted by the vast majority of educational institutions during this period. The view of education and its purpose reflected in them is similarly conservative, and represents the fundamental purpose of education not as the discovery of new knowledge, but as the successful and accurate transmission of an already established body of knowledge, chiefly taken from classical authors, and beyond which students were firmly discouraged from venturing.

The most striking visual representation of this occurs in a print by the French author Chéron, in which the student eventually finds his way barred by a forbidding image of the columns of Hercules bearing the words “Non plus ultra”. This was seen as a direct contrast to the engraved title page of Francis Bacon’s Novum Organum, which represents a ship sailing through the columns of Hercules. If the content of these thesis prints was conventional, however, their format, and the way in which they integrate text and image was anything but.

Single sheet publications summarizing a particular subject had existed from the early sixteenth century, but were initially not illustrated at all. When, around the middle of the sixteenth century, such publications did begin to be illustrated, these illustrations would generally be fairly simple, consisting perhaps of the coat of arms of the dedicatee, or a single emblem, and there would be a clear demarcation between text and image, generally with the image in the top half of the sheet, and the text in the bottom. It was only in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries that an attempt to integrate text and image began to be made.

These thesis prints were a conscious attempt both to entertain and to instruct and depended critically on an awareness of the capacity of visual information to interact with text as an efficient means of transmitting complex information. The prints were designed to be used in disputations, academic events in which students were required to defend or attack a series of given propositions in front of an invited audience. These disputations could be very lavish affairs, particularly when the students involved came from especially wealthy, noble or influential backgrounds.

The thesis prints would have been distributed to the audience, either in advance as a form of invitation, or during the event itself as a kind of programme to enable the audience to keep track of the propositions being debated. Public disputations were held to attract the attention of wealthy patrons and to enhance the prestige of the particular educational establishment. Thesis prints would have also been used by the students themselves as a form of mnemonic or crib-sheet to remind them of the material they needed to cover. Here, the integration of text and image in these publications can perhaps be related to the way in which, during this period, students were encouraged to memorize individual concepts by visualizing them as a specific physical location, and to relate concepts by seeing them as a journey from one location to another. Many thesis prints include a specific physical pathway that the reader is expected to follow.

Ms. Berger then went on to look at two specific examples of broadsides covering natural philosophy. The first of these was an illustrated thesis print designed in 1615 by the French Franciscan friar Martin Meurisse, and the second was an illustrated broadside designed in 1611 by Philander Colutius. Although Colutius’s broadside was most probably not a thesis print, he employed it as a teaching aid, likely referring to it during lectures to help students follow every step of natural philosophy. Both prints make use of the metaphor of the “theatre of nature”, a fairly conventional idea, suggesting man as the spectator of God’s creation and being both delighted and instructed by the experience. Although both publications are therefore using the same basic concept, they do so in very different ways. The print by Colutius depicts an actual classical theatre, broadly along the lines of the Colisseum in Rome, with the busts of various classical philosophers on the stage, accompanied by quotations from each philosopher. Above them, the theatre is on three separate levels, made up of arches, with the keystone of each arch representing a basic concept, accompanied by an appropriate image. The print by Meurisse, on the other hand, presents us with images of a series of figures, which appear to be acting out or representing the concepts Meurisse intends to convey through theatrical gestures, poses and props. The print also includes a depiction of Meurisse and his students, as well as of the Franciscan philosopher Duns Scotus.

Although some writers expressed reservations about the seriousness of these thesis prints as philosophical works, they were hugely influential, and continued to be valued and admired throughout the seventeenth century, both for their aesthetic and for their paedagogical value. Meurisse’s print on natural philosophy went through at least four editions, and was also translated into English (with a few adaptations to render it more suitable for a Protestant audience). The print by Colutius was also translated into English, as was another similar work by the sixteenth century Italian philosopher Andrea Bacci. The fact that these works were translated into English, and are known to have been used in universities in the Netherlands, tends to suggest that they managed to transcend the otherwise fairly strict division between Catholic and Protestant teaching of philosophy.

The final discussion explored all of these issues in more detail, as well as exploring other questions, such as the size of classes in universities during this period and especially the numbers of prints produced.

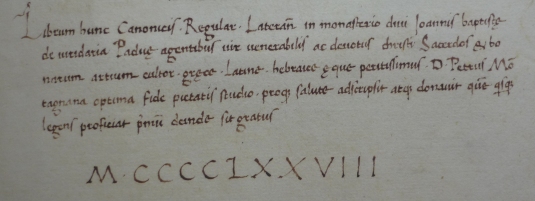

Bodleian Library Ashm. 1820b(18)