Category: Centre for the Study of the Book

Visiting Fellowships in the Special Collections of the Bodleian Libraries

The Bodleian Libraries offer Visiting Fellowships to researchers coming to Oxford to use the Special Collections of archives, manuscripts, rare books, ephemera, maps, and music. Fellowships support a period of study in the Weston Library for Special Collections.

The Bodleian Libraries offer Visiting Fellowships to researchers coming to Oxford to use the Special Collections of archives, manuscripts, rare books, ephemera, maps, and music. Fellowships support a period of study in the Weston Library for Special Collections.

The call is now open for applications for 2017-18. Deadline for applications is December 5, 2016.

See the Fellowships pages for details of Fellowships offered in particular fields of study, and for How to Apply.

http://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/csb/fellowships

Stuarts Online and animated

A web resource for schools, Stuarts Online, featuring materials from the Bodleian and Ashmolean has launched a video narrated by David Mitchell.

The Stuarts in Seven Minutes has been produced as part of the Stuarts Online initiative. Produced by academics at the universities of Cambridge, Exeter, Nottingham and Oxford, Stuarts Online includes twenty short films – each centred on a key text or artefact – which explore the stories, conflicts and personalities central to the history of Stuart Britain. It also provides lesson plans, biographies, timelines, and other learning resources. The films are enriched by privileged access to the holdings of the Ashmolean Museum and the Bodleian Library, of the University of Oxford. Their development was supported by further partnerships with the Historical Association and the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

Books as art and treasure: events from the Bodleian Libraries

BOOK COLLECTING: SCIENCE AND PASSION

The Bodleian Libraries award the Colin Franklin Prize for book collecting to a student of the University of Oxford every year. The competition for 2017 is now announced. http://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/csb/fellowships/the-colin-franklin-book-collecting-prize Hazel Wilkinson (Cambridge/Carr-Thomas-Ovenden Fellow at the Bodleian Libraries), winner of the first Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize at the University of London in 2014, will speak about building a book collection, in

‘“best edit.”: Book Collecting and the Hierarchy of Editions’

Monday 7 November at 5:15 pm in the Visiting Scholars’ Centre, Level 2, Weston Library.Entrance with University card, via the readers’ entrance, Parks Road.For information: contact Alexandra Franklin alexandra.franklin@bodleian.ox.ac.uk

THE MUGHAL HUNT

Lecture, 9 November 2016 1.00pm — 2.00pm, Lecture Theatre, Weston Library

Adeela Qureishi speaks about assembling the display of Mughal paintings depicting hunting scenes, from albums of paintings in the Bodleian collections.

The display is on view in the Proscholium, Old Bodleian Library.

This lunchtime lecture in the Lecture Theatre, Weston Library, is free but places are limited so please complete our booking form to reserve tickets in advance.

http://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/whatson/whats-on/upcoming-events/2016/nov/the-hunt-in-mughal-india

TOM PHILLIPS

A Humument: fifty years

14 November 2016 4.30pm — 7.00pm Lecture Theatre, Weston Library

In 1966, the artist Tom Phillips bought a copy of the forgotten Victorian novel A Human Document and started to work with it. With paint, cut-up and collage, he created a new story and a new kind of work: A Humument. The Bodleian is celebrating the final, fully revised, 50th anniversary edition with this book launch event.

Dr Gill Partington (University of Warwick) & Dr Julia Jordan (UCL); followed by dialogue between Adam Smyth (English Faculty) and Tom Phillips

This event is free but places are limited so please complete our booking form to reserve tickets in advance.

http://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/whatson/whats-on/a-humument

German manuscripts and prints in Oxford: events in honour of Nigel Palmer

In honour of Professor emeritus Nigel F. Palmer, the eminent German medievalist, there will be a two day programme of events on medieval German manuscripts and prints hosted by the TORCH Oxford Medieval Studies programme and the Bodleian Libraries.

On Friday, the Oxford Medieval Studies lecture Devotional Culture in Late Medieval Strasbourg is given by Stephen Mossman. This will be followed by drinks to celebrate both the British launch of Nigel Palmer’s latest publication, The Prayer Book of Ursula Begerin – a critical edition, with an art-historical and literary introduction, of an illuminated manuscript made for a Strasbourg laywoman – and his 70th birthday. Everybody welcome but please RSVP to Modern Languages Office office@mod-langs.ox.ac.uk if you would like to come, to make sure there are enough spaces and wine!

On the following day, a workshop will be held on the topic German Manuscripts and Prints in Oxford in the Lecture Theatre Weston Library, 9:15am-5pm. Again, everybody is welcome but please respond to Henrike Lähnemann henrike.laehnemann@mod-langs.ox.ac.uk if you would like to attend.

FRIDAY, 28 OCTOBER, TAYLOR INSTITUTION

LECTURE AND RECEPTION

17:00 Stephen Mossman: Devotional Culture in Late Medieval Strasbourg

18:00 Drinks Reception (Room 2)

SATURDAY, 29 OCTOBER, WESTON LIBRARY

COLLOQUIUM ‘GERMAN MANUSCRIPTS IN OXFORD’

09:15 Introduction and Welcome: Martin Kauffmann

09:30 Bodleian, MS. Germ. E. 22 & al. Strasbourg devotional manuscripts: Andrew Honey & Claudia Lingscheid & Monika Studer & Ruth Wiederkehr, Undine Brückner & Racha Kirakosian

11:00 Coffee break

11:15 Bodleian, MS. Douce 313 Franciscan Missal: Henrike Manuwald,

Bod-inc H-165 Book of Hours: Stefan Matter

Bodleian, MS. Opp. Add 4° 136 ‘Yiddish Songbook’: Elke Brüggen, Franz-Josef Holznagel

12:15 Bodleian, MS. Jun. 25 ‘Murbacher Hymns’: Michael Stolz

Merton College, MS 315 ‘Glosses’: Mary Boyle & Peter Kern

13:00 Lunch break (make your own arrangements)

14:45 Bodleian, MS. Hamilton 46 ‘Boethius’: Daniela Mairhofer

15:00 Bodleian, MS. Laud. Misc. 479 ‘Paradisus anime intelligentis’: Freimut Löser & Volker Mertens & Ben Morgan

15:45 Bodleian, MS Douce 367: Platterberger Chronicle: Linus Ubl

Bodleian, Bod-inc B-504 / R-32: Bettina Wagner

16:15 Taylorian, MS. 8° G. 2 Bruder Philipp, ‘Marienleben’: Kurt Gärtner & Christina Ostermann

16:45 Right to respond / Conclusion: Nigel F. Palmer

17:00 End of proceedings

Henrike Lähnemann

Professor of Medieval German * Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages * 41 Wellington Square * UK – OX1 2JF Oxford * 0044 1865 2-70498 * Follow @HLaehnemann * Visit the Reformation 2017 at the Taylorian Institute website

Editors learn about paper, quills, and ink for closer reading

Members of the editorial board of the Oxford edition of Thomas Traherne’s (c. 1637-1674) works took part in a one-day workshop at the Weston Library, studying the ink and handwriting in manuscripts associated with Traherne’s works, including handwritten corrections in printed editions. They were guided by Jana Dambrogio, Thomas F. Peterson (1957) Conservator at the MIT Libraries, and a Sassoon Visiting Fellow at the Bodleian this month.

The first part of the workshop, hosted at the Bodleian Conservation studios by Andrew Honey, involved making iron gall ink (which has a dramatic colour change) and copper gall inks.

Participants had a chance to write with goose quills and steel nib pens on handmade paper, using chancery paper from the University of Iowa Center for the Book , with the help of papermaker Timothy Barrett.

Andrew and Jana talked about the western hand paper making process, ink making, quill shaping, and showed examples of other writing tools and materials (handmade sealing wax, stamps, paper making mould, pounce pots, etc.)

Participants all received a locked letter and later, in a seminar session, looked at three examples of folding techniques used by Thomas’s brother Philip Traherne (1635-1686), in letters preserved in Bodleian collections. Examination of major Traherne items from the collections, and additional material kindly lent by college libraries of Balliol, Brasenose, and Queen’s Colleges, formed the second part of the day. Balliol and Brasenose college library staff participated in the day with the Traherne editors.

The Oxford Bibliographical Society provided the funding for this workshop for the Oxford Traherne team.

The Oxford Traherne edition website: http://oxfordtraherne.org

Bodleian Fellows Research, Summer 2016

Some of the Bodleian Visiting Fellows awarded grants for research visits in 2016-17 have started arriving at the Weston Library.

Jana Dambrogio (Thomas F. Peterson (1957) Conservator, MIT Libraries), Sassoon Fellow, is examining ‘locked letters’ in Bodleian collections. [See an earlier blogpost here] Her first challenge is to discover the material, by looking through collections of letters from the 16th and 17th centuries. She consulted Mike Webb, curator of early modern manuscripts, and they started looking at volumes of letters in which Dambrogio identified distinctive styles of folding and sealing, the kind of usage which her research will examine in detail.

On August 9, the Bodleian Fellows Seminar heard from Laura Estill (Texas A&M), the Renaissance Society of America-Bodleian Visiting Fellow. Dr Estill has been working on the Edmond Malone collection, and she compared Malone’s collecting of Elizabethan plays to the collection of John Phillip Kemble, which is now held in the Huntington Library, and spoke about the significance of collections like these, made from the second half of the 18th century onwards, in shaping the canon of early modern plays.

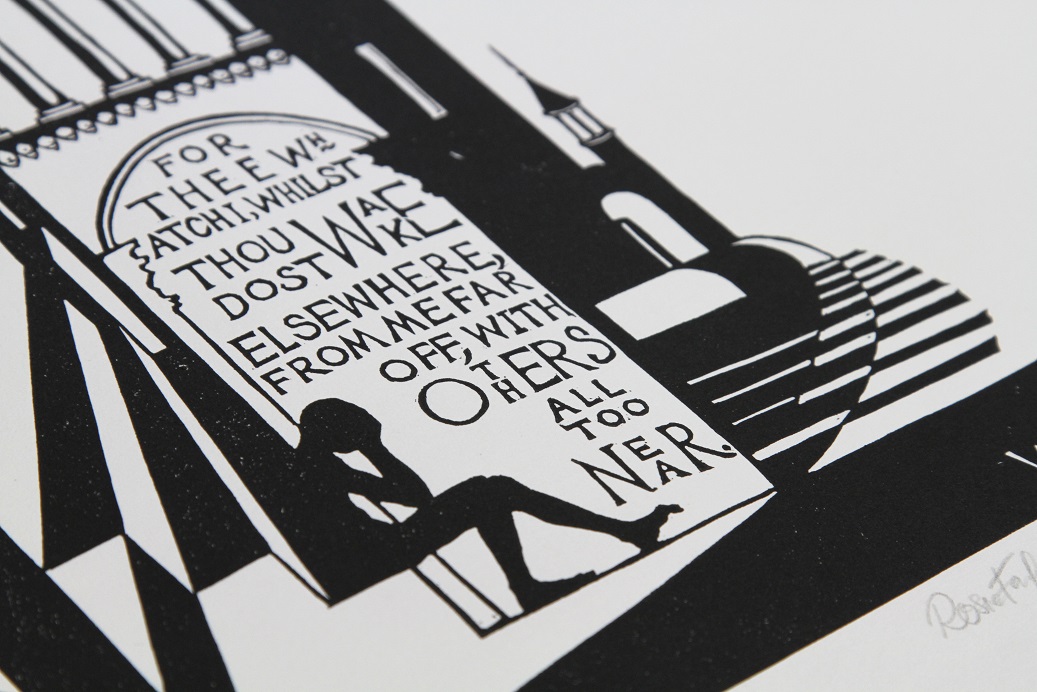

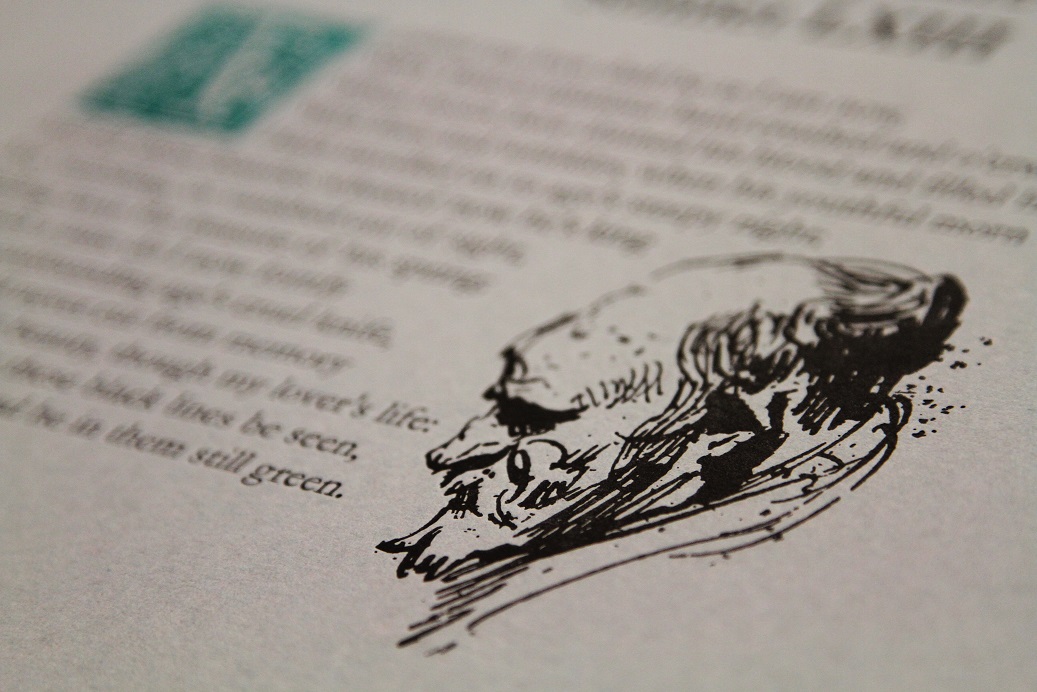

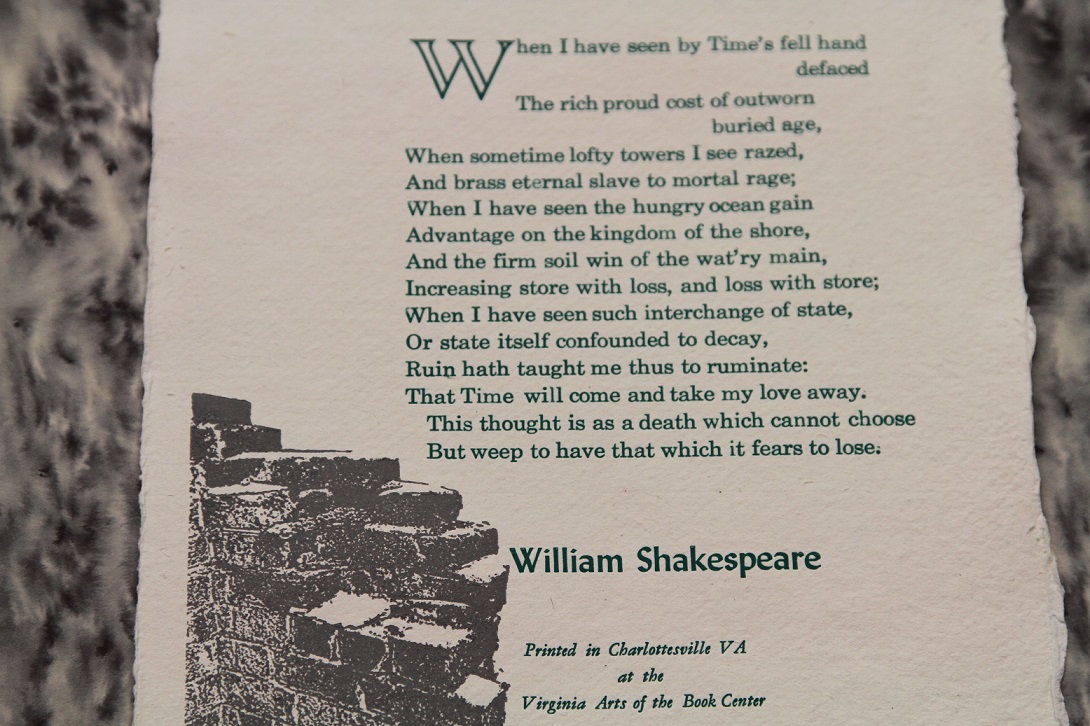

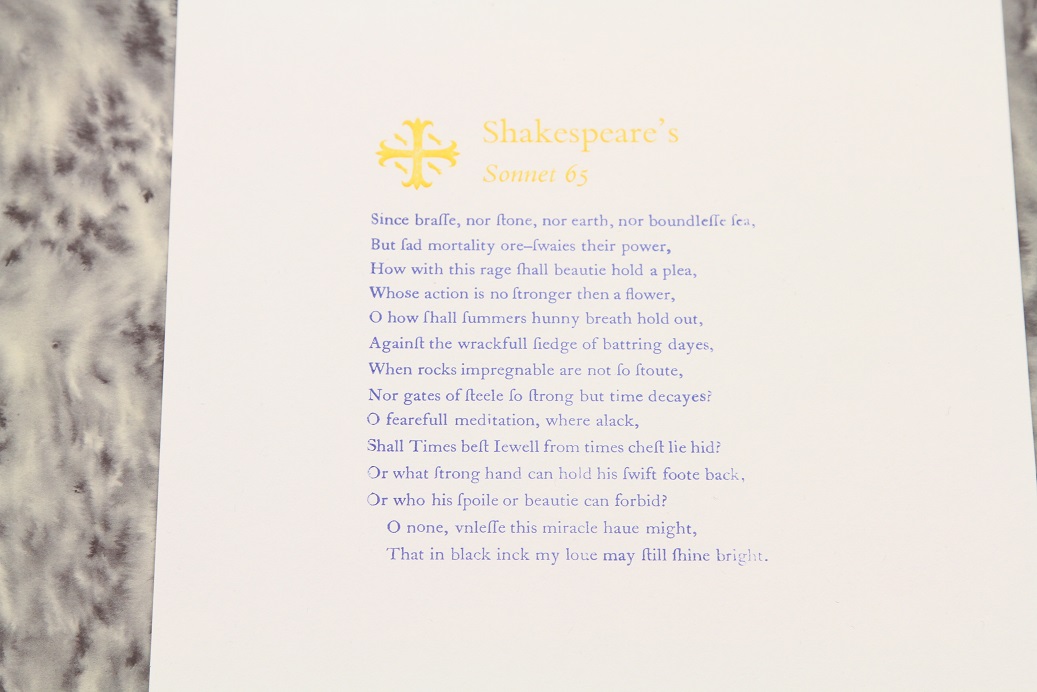

Shall I compare thee to a sans-serif?

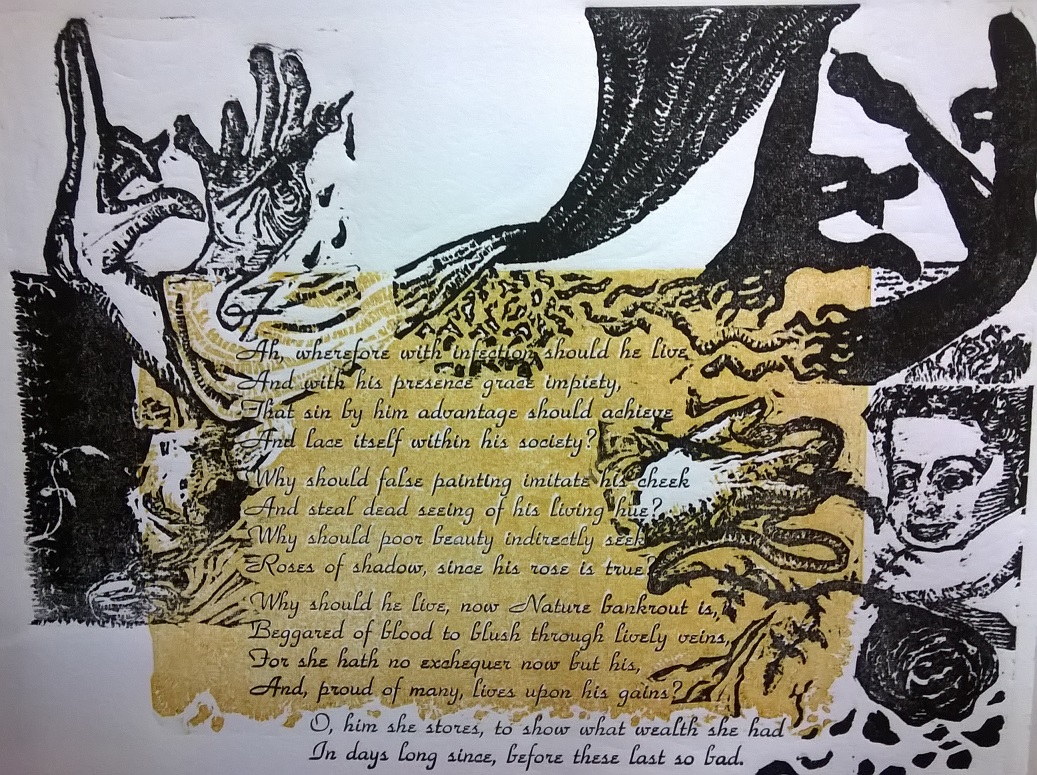

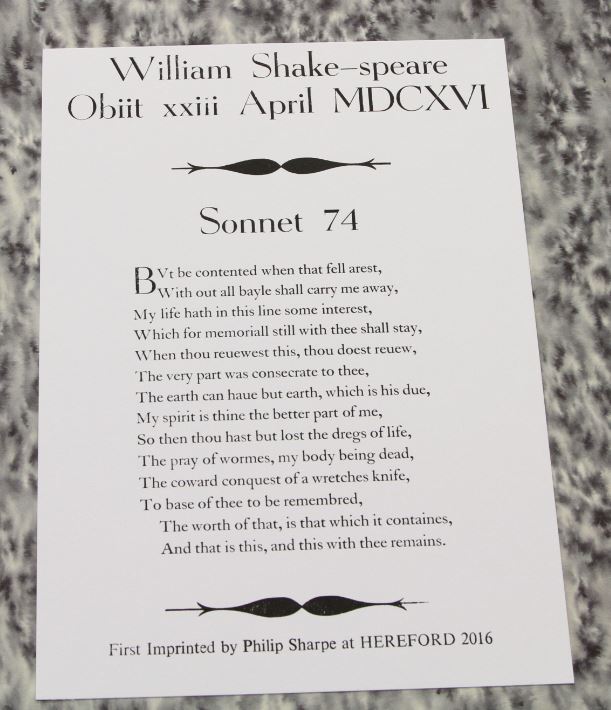

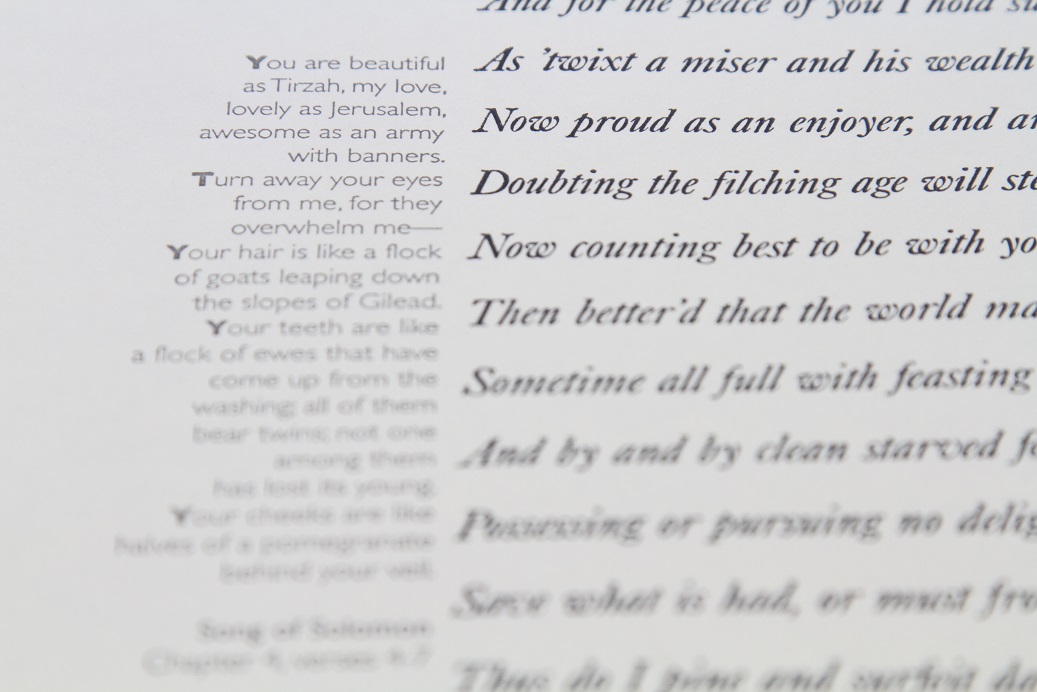

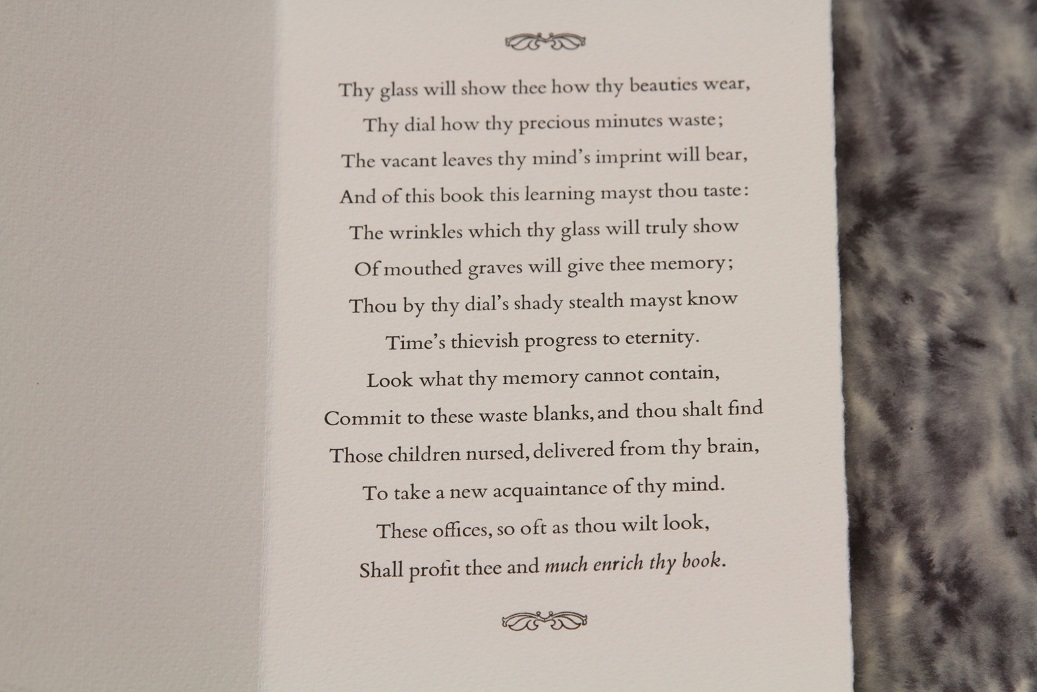

The Shakespeare sonnets collected in 2016 contain an astoundingly broad range of printed versions, coming from a wide range of printers from around the world. I recently looked through some of these and was fascinated to discover the many differences between the different editions, which caused me to ponder whether to write Shakespeare using a different typeface, orthography or other presentational choice is to reproduce precisely the same essential message.

Take, for example, the difference between two different editions of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 (“Shall I compare” etc) which were presented side-by-side to one another. One, taken from Shakespeare’s 1609 First Folio, is written with Shakespeare’s original spelling and orthography, now fairly antiquated in its use of such archaisms as “u” in lieu of “v”, or the “long s” (“ſ”). In contrast, the second version, taken directly from Wikipedia, not only uses a modern sans serif typeface, but also a modern and standardised form of spelling throughout.

For the modern reader, this functions as something of a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it could be argued that placing Shakespeare in a modern typeface and orthography causes him to appear more directly relevant to an audience more familiar with that more contemporary style. But it could also be seen to appear strangely synthetic and divested of its original meaning. It could be seen to lose something of its “authenticity”. A rather vague term, this could be here seen to refer to a certain consistency between the physical appearance of a work and the cultural context in which it originated. To take an Elizabethan poem and write it down in a modern style could be seen by some as deeply jarring in its inconsistency.

This then raises the important question of whether, as Ben Jonson said, “[Shakespeare] was not of an age, but for all time” or whether there is some specific temporal quality to his work that necessitates it being placed into its original cultural context. This is the same debate which tends to come into play, for example, when it is debated whether Shakespeare should be staged in modern or period costume. Several of the sonnets printed for this project gesture towards “authenticity”, with Sonnet 105 (“To me, fair friend” etc), from earlier this year, while at first appearing mock-Elizabethan through its antiquated typeface and use of illustration, nonetheless, upon closer inspection, also making use of modern orthography. The implication may be then that a balance must be preserved, so that Shakespeare’s message may retain more or less its original meaning, but also be capable of altering that meaning in subtle ways in order better to fit a contemporary cultural context.

For modern readers, there is a certain value both in understanding Shakespeare’s work as it originally would have been and as it is now and therefore a certain value in comprehending how the way in which Shakespeare is written could be seen to affect what it means.

from Benjamin Maier, Intern at the Bodleian Libraries

Woodblock printing: history, art, and science

On Friday 17th June 2016, the Centre for the Study of the Book hosted a workshop on the history, science and art of woodblock printing. Organized by Dr. Giles Bergel under a Katharine Pantzer Fellowship from the Bibliographical Society of America, the workshop focussed on English woodcutting and wood-engraving with particular reference to the so-called Charnley-Dodd collection of original wooden printers’ blocks assembled in Newcastle in the mid nineteenth century, used by several generations of Newcastle printers to print illustrations for ballads and chapbooks.

Opening the proceedings, Dr. Bergel offered a brief history of the printers and their blocks, offprints of which can be seen in an 1858 catalogue produced by Newcastle printer Emerson Charnley, and in an 1862 catalogue of the same set of blocks, with additions, issued by William Dodd. The workshop was fortunate to have to hand the Bodleian’s copy of the Charnley catalogue, and even an original woodblock employed in the 1862 Dodd group in the possession of Graham Williams.

Charnley-Dodd woodblocks are also to be found in McGill University Library ; the British Museum ; and the Huntington Library. Dr. Mei-Ying Sung next spoke on her work on cataloguing the large Armstrong Collection of woodblocks in the Huntington, including Charnley-Dodd blocks. A theme of the day, expressed also by Dr. Elizabeth Savage, Judith Siefring, Dr. Melanie Wood and others, was the necessity for collection histories and cataloguing standards for these printing materials, held in libraries, museums, working collections and elsewhere, that pose particular challenges for researchers and curators.

The workshop next heard from Barry McKay on the woodcutter only known by the initials ’RM’ on Charnley and other blocks employed to print chapbooks in Cumbria and elsewhere, some copied from stock blocks used over two centuries previously: the presentation testified to the power of combining bibliographical analysis of impressions, together with external evidence taken from book trade history.

There was a joint presentation from two members of Oxford’s Visual Geometry Group . Professor Andrew Zisserman explained the methods behind the ImageMatch tool , implemented by Visual Geometry alumnus Relja Arandjelovic in Bodleian Ballads Online. Joon Son Chung presented his award-winning ImageBrowse tool , the sorted output of ImageMatch clustered by block and under semantic ICONCLASS keywords (the work of Dr. Alexandra Franklin for the original Bodleian Ballads Database). ImageBrowse provides powerful visualisations of woodblock degradation over time as well as tools for comparing common, similar and neighbouring block-impressions. The work of Visual Geometry met with acclaim from all participants, as it has done throughout the bibliographical community.

Martin Kochany from Hot Bed Press, Salford, presented a diagrammatic overview of the processes, objects and relationships under discussion, paying particular attention to methods of how blocks can be copied (in some cases, very accurately: see for example, the Bodleian’s early ballad collections ).

Martin argued that printers will always find pragmatic solutions to the problem at hand, whether by ad-hoc block-repair, block copying or touching-up printed sheets by hand: ‘bodging’ is the norm. The matter of bodging engaged many of the other practitioners present, including Paul Nash, who presented a ‘dabbed’ type-metal cast of a woodblock made by him and Giles Bergel ; Richard Lawrence , Martin Andrews and Graham Williams, who presented some American woodblock-repair plugs (plugged holes can be seen in several Charnley blocks). Martin Kochany cautioned researchers trying to sequence apparently unique woodblocks to be aware of printers’ panoply of bodges, and to look for the contradictory or marginal cases that might define the norm.

The workshop briefly touched on the relationship between woodcut and wood-engraving. There was discussion of the tolerances of a woodblock used over a long working life, and how the development of wood-engraving was both a more robust and a more refined process, Nigel Tattersfield bringing his immense knowledge of the career and work of Thomas Bewick to bear on the subject. Melanie Wood’s account of three linked collections at Newcastle University’s Robinson Library (the White , Burman-Alnwick and Crawhall collections) also opened the discussion out from the Charnley-Dodd collection to a broader history of woodcutting and illustration design.

The workshop then concluded, but was immediately followed by a public lecture from workshop participant Professor Blair Hedges , who presented his work on the science of woodblock illustrations, with particular reference to species of woodworm and to the cracking of blocks, or of carved lines, in relation to the woodgrain or to the thickness of the line. A response was given by Reading University lecturer Martin Andrews : an appreciative and lively discussion chaired by Giles Bergel then ensued, engaging an audience of bibliographers, printing practitioners, book and print historians. The quality of the discussion vindicated the approach of the workshop in bringing together scientists, practitioners and historians, and testified in particular to the importance of Blair’s research. A drinks reception was held, fittingly, at the Bodleian’s Bibliographical Press.

Research continues, in the form of ongoing and new collaborations – in particular around dabbing and other block-reproduction methods, the application of Computer Vision technology to the study of printing, and the history of technique, materials and style in wood-engraving.

The workshop was funded by the Bibliographical Society of America and the English Physical Science and Research Council as part of the SEEBIBYTE project . It was supported by the Bodleian Libraries Centre for the Study of the Book.

from Giles Bergel

Shakespeare in 2016: podcasts of lectures in the Weston Library

Four hundred years after his death, these talks by specialists revisit Shakespeare’s works, life, and times in the light of current research, as part of the Shakespeare Oxford 2016 festival and in connection with the Bodleian Libraries exhibition, ‘Shakespeare’s Dead’.

Bart van Es, 1594: Shakespeare’s most important year

By examining the early modern theatrical marketplace and the artistic development of Shakespeare’s writing before and after this moment, it is hoped that this talk shows why 1594 was, by some measure, Shakespeare’s most important year.

Jonathan Bate, The Magic of Shakespeare

It will argue that Shakespeare inherited from antiquity a fascination with the intimate association between erotic love, magic and the creative imagination, and that this is one of the keys to the enduring power of his plays.

Sir Jonathan Bate, Provost of Worcester College and Professor of English Literature at Oxford University, is one of the world’s most renowned Shakespeare scholars, the author of, among many other works, Shakespeare and Ovid, The Genius of Shakespeare, Soul of the Age and (as co-editor) The RSC Shakespeare: Complete Works. He co-curated Shakespeare Staging the World, the British Museum’s exhibition for the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad, and he is the author of Being Shakespeare: A One-Man Play for Simon Callow, which has toured nationally and internationally and had three runs in the West End.

Steven Gunn, Everyday death in Shakespeare’s England

Coroners’ inquest reports into accidental deaths tell us about the hazards of everyday life in Shakespeare’s day. There were dangerous jobs, not just building, mining and farming, but also fetching water, and travel was perilous whether by cart, horse or boat. Even relaxation had its risks, from football and wrestling to maypole-dancing or a game of bowls on the frozen River Cherwell.

Peter McCullough, Donne to Death

John Donne’s sermon, Death’s duell, was part of an early Stuart vogue for funeral sermons. Professor McCullough discusses Donne’s contribution to this genre, and looks at how this tradition is connected to the poetic and dramatic representations of death on display in the exhibition, Shakespeare’s Dead.

Katherine Duncan Jones, Venus and Adonis

In 1592-93, with London playhouses closed because of plague, Shakespeare wrote his most technically perfect work. Venus and Adonis (1593) is a highly original ‘take’ on the ancient Greek myth of the doomed Adonis – presented here as a pubertal boy incapable of responding to the goddess’s amorous advances. It was a tearaway success with Elizabethan readers.

Emma Smith, Memorialising Shakespeare: the First Folio and other elegies

Ben Jonson wrote in 1623 that Shakespeare ‘art a Moniment, without a tombe/ And art alive still, while thy Booke doth live’: centuries later Jorge Luis Borges observed that ‘when writers die, they become books’, adding, ‘which is, after all, not too bad an incarnation’. This lecture considers Shakespeare’s First Folio as a literary memorial to Shakespeare, alongside other elegies, epitaphs, and responses to the playwright’s death.