Ian Maclean’s presentation to the History of the Book seminar on 8 November 2013 developed the themes of his 2012 book, Scholarship, Commerce, Religion:

The Learned Book in the Age of Confessions, 1560–1630, with an examination of the changes evident over the next hundred years after 1650 in the marketing and sales of learned books, taking law books as an example.

This paper addressed the question: what would scholars of learned Latin texts in 1600 and 1750 have perceived as radical differences in the material conditions of publishing (getting published, getting distributed, getting hold of published materials from the recent and more distant past, building their own libraries) and financing all this?

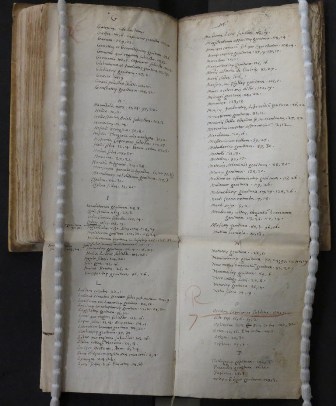

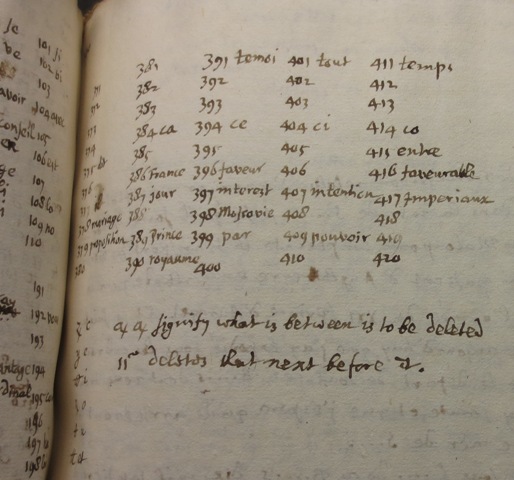

The paper took the case of two very extensive thesauruses of legal humanism, from the 1720s and the 1750s. The first was the Thesaurus Juris Romani, (4 vols, Leiden, Johannes vander Linden, 1725-6, fol.), containing 77 items of republished material mainly from France and Spain. It was edited by Everhard Otto (1685-1756), Professor of Law at Utrecht, mainly from the library of Cornelius van Bynkershoek (1673-1743), President of the Supreme Court of Holland. Later editions appeared in 1733-5 and 1741-4. The second thesaurus was the Novus Thesaurus Juris Civilis et Canonici, (7 volumes, The Hague, Pieter de Hondt, 1751-53, fol.) This consisted in 105 items, also principally from France and Spain, mainly from the Library of the editor, Gerard Meerman (1722-1771), Pensionary of Rotterdam.

Before 1650, the Frankfurt Book Fair was the best vehicle for achieving a sale throughout Europe. After 1650, the United Provinces took over the role of international publishing, and achieved this by exploiting the organs of the Republic of Letters (scholarly journals such as the Acta Eruditorum and the Journal des Savants), by using the subscription method of achieving sales, and by engaging in an impressively wide network of bookshops throughout Europe. The constituency of readers of the two Thesauruses show that in the middle of the 18th century, publishers depended on purchasers who were not themselves in the field, and whose motives for purchasing were often driven by prestige and vanity. The evidence of the subscription lists of the two Thesauruses suggests however that sales outside the Netherlands and Germany were sparse. We may contrast this state of affairs with that which obtained before the Thirty Years War, when there seems to have been almost unlimited optimism about the commercial viability of legal tomes in other countries of Europe.

Discussion at the seminar centred on the costs of publishing and the luxuriousness of the editions described and considered individuals named in the lists of subscribers, and their potential motives.