from Martha Repp

The fifth in the 2012 series of the Oxford Seminars on the History of the Book was held at All Souls College, Oxford, on 17 February, 2012. Professor Raphaële Mouren of the École nationale supérieure des sciences de l’information et des bibliothèques (ENSSIB) in the University of Lyon spoke on “The humanist editor as author”. Her paper provided a fascinating insight not only into concepts of authorship in the sixteenth century, but into how scholarly editions of classical texts were prepared during this period.

For the purposes of Professor Mouren’s paper, the term “humanist” was understood to mean a scholar who reads, studies, revises, corrects, and edits classical texts for the purpose of producing a “reference edition”, that is to say an edition that will be used for preference by scholars working on a particular text. The person responsible for producing such an edition can be referred to as a “reference editor”, although there were also examples of “reference printers”, where the same person would be responsible both for the intellectual work of preparing the text, and for the physical production of the edition itself. The best known examples of such reference printers are perhaps the Manutius family in Venice or the Estienne family active in Paris and Geneva.

So, can these humanist editors of classical texts be considered as authors in the same way as the creators of original texts in the vernacular? And where can we look to find evidence of their activity? The most obvious place to start is by looking at the information provided in the editions themselves, and particularly at title pages, dedicatory letters, colophons, and other paratextual material. It is important to bear in mind in this context that the inclusion or omission of particular information on the title page, and the way in which that information is presented, are the result of conscious or unconscious decisions. These decisions will generally have been made by the printer; the specific format of the title page was in the sixteenth century, and generally still is, one of the few aspects of an edition over which the author or editor has no control. If the printer controlled the title page, the editor had an equivalent control over the dedicatory letter, and many humanists used such letters as a means of asserting their editorship of the text, and of spelling out the editorial strategies adopted and the problems encountered. One might expect the title page to an edition of a classical author to provide the name of the original author, the name of the editor, and the name of the printer or publisher. When looking at sixteenth century editions of such texts, however, it is striking how frequently the information provided on the title page is incomplete, or does not match the reality of how the edition was actually prepared.

As the reasons for these omissions or inaccuracies tend to vary from edition to edition, the remainder of Professor Mouren’s paper was devoted to looking at specific examples. These examples were chiefly taken from the editions produced by Pietro Vettori, a university lecturer and prolific editor of classical texts active in Florence in the mid- to late-sixteenth century.

The first example chosen was the three editions of the pseudo-Demetrius Phalereus’s De elocutione, printed in Florence between 1542 and 1562, all edited by Vettori and printed by the Giunta family. The title page of the 1542 edition merely gives the name of Demetrius Phalereus, the title of the work, and the date of publication. A colophon adds that the work was printed in Florence, but not much more. This lack of information may possibly be explained by the fact that the edition is in fact simply a reproduction of an existing edition of the text, and it was not usual for editors to be credited unless they had done substantial work on the text. An additional explanation may lie in the circumstances in which the edition was produced; it was printed at the beginning of the university year, and it is therefore probable that this was a text that Vettori intended to use in his university teaching, and that the priority was to have the edition available to his students as quickly as possible. This 1542 edition may even have functioned as a starting point from which Vettori and his students would go on to correct and revise the text. The extent of the editorial work Vettori ended up doing on this particular text is perhaps indicated by the difference in wording of the title page to the 1562 edition, which is described as Vettori’s commentary on Demetrius Phalereus, despite the fact that the edition includes both the pseudo-Demetrius’s original text, and a Latin translation of it.

The next example considered was the edition of Cicero’s complete works published by the Giuntas in Venice in 1537. The edition consists of four volumes of Cicero’s works, the first volume edited by Andrea Navagero and the remaining three volumes edited by Vettori. The title page to volume one does indeed credit Navagero as editor, but the title pages to volumes 2-4 make no mention of Vettori. In fact, the only mention of Vettori’s input is as the author of an ancillary volume of “Emendationes”. This is probably explained by the fact that in 1537, Vettori was only at the beginning of his career, whereas Navagero was already an established name, and therefore Navagero’s name, unlike Vettori’s would have been seen by the publishers as adding scholarly weight to their edition.

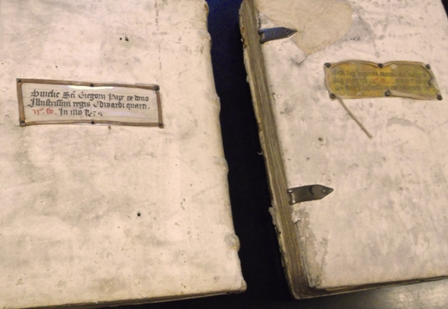

Vettori’s editions of Clement of Alexandria, Porphyry and Sallust are interesting in that they do not mention Vettori’s name on the title page, but do specify the manuscript he used to prepare his edition, the text selected being described as “E Bibliotheca Medicea”. It was common practice to indicate that a famous or important manuscript had been used in the preparation of an edition, since this was seen by printers as a way of making their edition seem newer and better than any of the other existing editions.

A final example considered was the various editions of Cicero’s Epistolae familiares published by Paulus Manutius during the sixteenth century. When Paulus Manutius published his first edition of the Epistolae familiares in 1540, he did not mention his own involvement either as editor or as publisher on the title page. As a result of this, when Vettori began work on his own edition of Cicero, he had to ask his own publisher, Bernardo di Giunta, to find out who had been responsible for the 1540 edition of the Epistolae familiares. When told that it had been Paulus Manutius, Vettori couldn’t quite believe it, and referred to the edition rather dismissively. This then left Paulus Manutius with the problem of how to record his own involvement as editor and publisher on the title page, and in his subsequent editions of the Epistolae familiares, he experimented with a number of different ways of achieving this, most of which involved his name appearing on the title page in two different places. Eventually, however, he settled on the formula “Corrigente Paulo Manutio”, used as an imprint, but also acknowledging his editorial input.