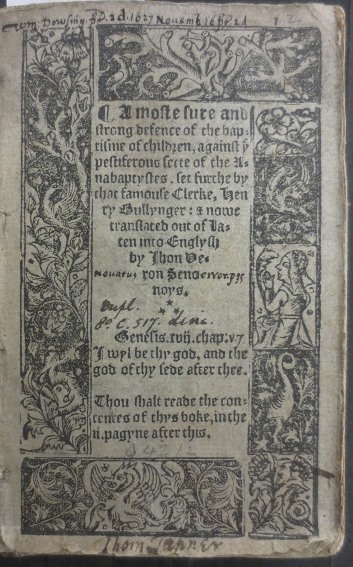

I’ve been looking at the neat handwritten annotation at the top of a page in the Bodleian Library’s copy at Tanner 942(2) of A moste sure and strong defence of the baptisme of children, published in 1551, guided by Dunstan Roberts (Cambridge) in the latest of the master classes convened at the library by Will Poole.

The annotation is by William Dowsing (1596-1668) of Suffolk, noting his purchase of this short book in November, 1627. At the end of the pamphlet, he notes the dates that he read this work, over two days in the following February.

A tidy mind is a wonderful thing. Was this useful in Dowsing’s later role as ‘Commissioner for the destruction of monuments of idolatry and superstition’, carrying out the ordinances of Parliament in 1643 and 1644? Dowsing’s collection included several books of the 16th-century Reformation, which he seems to have pored over, refining his sense of Puritan outrage at any idolatry or beliefs unsupported by scripture, annotating with chapter and verse where the earlier authors were sloppy in their references.

Roberts presented Dowsing as a case of the long historical tail of the Henrician reformation. In the process, he pointed to several bibliographical puzzles and possibilities.

One was the tantalizing detail in which Dowsing recorded not only the date of purchase, but the date and duration of his reading of books. How the history of reading would benefit if all readers were so systematic!

A puzzle was the fate of Dowsing’s collection of pamphlets. His systematic re-numbering of the pages in his own collected volumes laid a trail of clues to his collecting and arrangement of books that are now broken up and dispersed.

How can modern scholars find, and share, these small traces that can add up to a picture of larger lost libraries? The series convener of the master classes on printed books with manuscript contents, Will Poole, has reconstructed the library of Francis Lodwick from lists in the Sloane manuscripts at the British Library and from clues in Bodleian and British Library books, such as marginal annotations and shelfmarks (The Library, 7th Series, vii(2006), p.377-418). The Hans Sloane printed books project has followed Sloane’s distinctive marks to identify his own printed books inside and outside the British Library. http://www.bl.uk/reshelp/findhelprestype/prbooks/sloaneprintedbooksproject/sloaneprinted.html

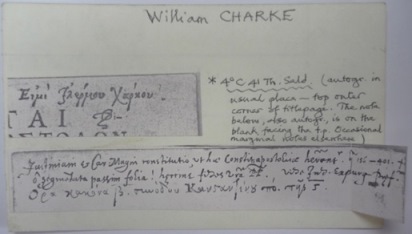

The American Library Association rules for descriptive cataloguing of rare books specify that provenance information for copies held by a library should be included in catalogue records for those copies. We also know that librarians and scholars have been keeping independent records of this sort of information for years, as in this example from a card catalogue compiled by the late D.M. Rogers at the Bodleian, recording coats of arms, autographs, and notes and sometimes reproducing these.

This kind of information might be useful only as threads to knit together collections long since scattered. What methods will help scholars to find information on a book they are looking at, and what will enable their contribution to a collective effort to increase the knowledge held in libraries about the history of the books and manuscripts in their care?

The database of Material Evidence in Incunabula (MEI) hosted by CERL, gathers provenance information for incunabula. http://www.cerl.org/resources/mei/main.

David Pearson’s list of English book owners in the 17th century is a PDF file available on the Bibliographical Society website simply organized alphabetically by name of owner, with links to images showing autographs and other distinctive marks. http://www.bibsoc.org.uk/content/english-book-owners-seventeenth-century

Can researchers be empowered to contribute information as they find it in libraries around the world? On LibraryThing, Legacy Libraries (http://www.librarything.com/groups/iseedeadpeoplesbooks) enables collective efforts to build a virtual library catalogue by adding records of editions that were owned by an individual.

The CERL web portal offers a question board, for those who are confronted with an unknown bookplate or signature. http://www.cerl.org/resources/provenance/can_you_help.

How well do any of these methods enable a researcher a) to learn what is known, about a book or an owner; b) to find out what is still unknown; c) to estimate the costs and benefits – (Is It Worth It?) – of pursuing an anonymous annotator or of reconstructing a lost library?

And in what format can this help be provided? When is the information best conveyed by standard vocabularies and thesauri, integrated with authoritative bio-bibliographical information? Or on the other hand by visual databases of distinctive marks shared among researchers labouring in the same vineyard? Online folders of snapshots already enable libraries to organize evidence into groups (bookplates, inscriptions) for visual identification and matching, as here from the Bodleian Libraries CSB: http://www.flickr.com/photos/oxford_csb/ and the much more extensive Penn Provenance Project image stream: http://www.flickr.com/photos/58558794@N07/.

A controlled vocabulary in a prescribed format, or a gallery of graven images: what would William Dowsing say?