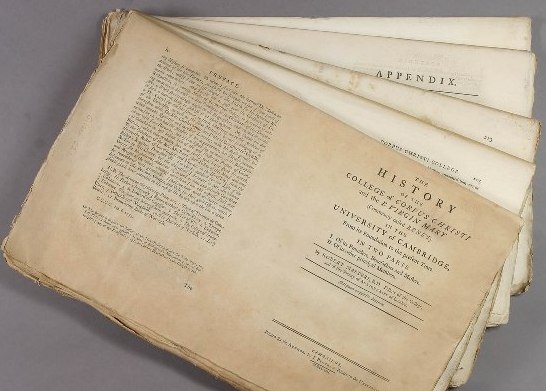

‘The Gathered Text’ cut a cross-section through current book-historical studies, taking a highly original view of the subject from a new angle. (Gathering, quire, signature … look inside with this display.) As defined by Rebecca Bullard, who convened this symposium, the gathering suggested not only the sheet of paper or parchment constituting a standard unit of book production (whether in manuscript or print) but importantly the transformative actions — of folding, stacking, and sewing — that made these sheets into books.

Randall McLeod (University of Toronto), ‘Omnium gatherum’.

Randall McLeod’s keynote speech brought to mind the journalistic genre of dance criticism in eloquently reconstructing in words the trajectory and effect of physical actions that have left no record, but in this case only their product. He described the progress of a bookworm through the leaves of a Hebrew book stored in a warehouse, not yet folded into the quarto gatherings it later became. Then he described the effects of a hastier gathering of sheets: offsettings in the 1732 Bentley edition of Paradise Lost, as he demonstrated, were created by the human movements of stacking sheets still too fresh from the press.

Following McLeod’s lead, all the speakers on 3 September contributed to this dynamic view of the gathering as product of movement. In some cases the graceful partnership of a dance was suggested, while at other times the inclusion or excision of gatherings seemed to be the object of contention and struggle.

Nicholas Pickwoad (University of the Arts, London), ‘Bookbinders’ gatherings’.

Andrew Honey (Bodleian Library Conservation Unit), ‘Stitched pamphlets and blank memorandum books – two atypical approaches to making gatherings’.

Henry Woudhuysen (University College London), ‘Gatherings in private press books’.

The first panel of papers explored different types of relationship between printers (of sheets) and binders (of gatherings).

Nicholas Pickwoad outlined conflicts that could occur between the delivery of printed sheets and the efforts of binders to create a durable volume that would open to display the pages as intended. He showed how binders used a variety of hinges and sewing styles to compensate for the variety of printed material they might receive, whether large, expensively-produced engraved plates opening the full width of a volume, or books cheaply printed in single bifolia.

Andrew Honey looked at 17th-century pamphlets for which printers had provided pseudo-wrappers of single bifolium comprising a title page and blank endleaf. The suggestion that these pamphlets were recognized, even at the time of their printing, as likely to endure a different physical fate to other books intrigued the symposium; many now surviving in libraries have surely been rebound into volumes, with a possible loss of this kind of evidence.

In Henry Woudhuysen’s account of the Kelmscott and Doves Presses, we heard of the situation opposite to that outlined by Pickwoad; these private presses, seeking to present a total design, took responsibility for both printing and binding. Following the maxim of William Morris, who urged that the well-balanced opening was the most important aspect of a book, they encountered their own challenges in ensuring harmony between separate gatherings.

David McKitterick (Trinity College, Cambridge), ‘Producing and selling monsters’.

Rebecca Bullard (University of Reading), ‘Margaret Cavendish’s gathered texts’.

John Barnard (University of Leeds), ‘Dryden’s Virgil (1697): Gatherings and politics’.

Ian Gadd (Bath Spa University) ‘Fooling Lord Wharton: The second edition of Swift’s The Publick Spirit of the Whigs (1714)’.

Papers in the afternoon by David McKitterick, Rebecca Bullard, John Barnard and Ian Gadd addressed the ways in which gatherings allowed early modern authors and publishers an incremental approach to constructing – or deconstructing – a book.

McKitterick considered how booksellers influenced the way books were presented, through the bibliography of Henry Smith’s sermons. The bulk of these were published posthumously in the 1590s, in volumes of what were evidently separately printed sermons. (STC 22716-22783.7) The complications of the separate printings and variant issues of these collections drove STC bibliographers to allow the heading ‘Henry Smith, Monster’ (instead of Minister) to be ‘mis’printed in this entry.

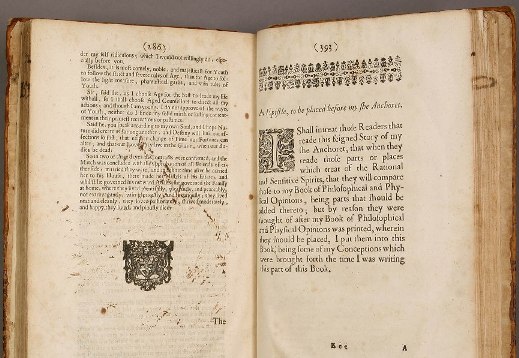

Authorial interventions also disturbed the order of gatherings. Rebecca Bullard traced the efforts of the 17th-century royalist Margaret Cavendish to publish, from exile, her poetry and natural philosophy through the printers Martin and Allestrye in London. Cavendish’s multiple interjections, sent to the printers while her books were in press, appeared to reflect her concern to express the evolution of her ideas over time. However monumental these folio volumes might become in the press, the disrupted pagination and interjected ‘Addresses to the Reader’ allowed Cavendish afterthoughts and restatements, undermining any tomblike fixity of the text. Was this also, asked Bullard, a means of drawing attention to her exiled state?

Deep political divisions between author and printer were at work, argued John Barnard, in the publication of John Dryden’s Virgil, printed by the Whig-supporting Tonson in 1697. While Tonson commissioned illustrations depicting Aeneas with the visage of William III, the dedications by Dryden to Catholic, Jacobite, and Tory peers were evidently delivered after the body of the work had been printed, and formed separate signatures.

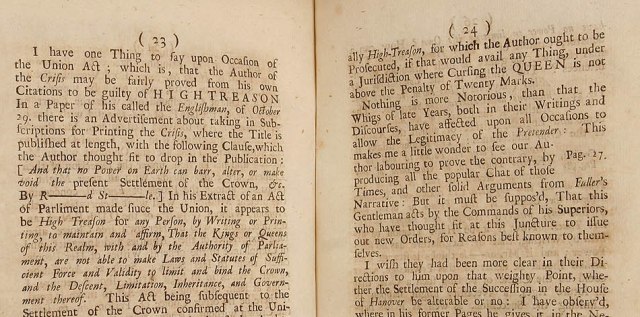

In 1714 a threatened prosecution led, as Ian Gadd showed, to a mysteriously disappearing gathering, the surreptitious replacement of pages in an anonymous pamphlet by Jonathan Swift, ‘The Publick Spirit of the Whigs’. The result was that Lord Wharton, preparing to read the incriminating passage aloud in Parliament, found that his ‘copy’ of the pamphlet was missing the relevant pages. In fact he had the unacknowledged second edition lacking the offending text. Remarkable in this story was that the disrupted pagination of the expurgated (new) edition appeared not to arouse suspicions — a comment either on the attentiveness of readers or on the expected standards of pamphlet printing.

Peter Stallybrass (University of Pennsylvania), ‘Strings, thread, pins, wire, laces and folds’

Kathryn Sutherland (University of Oxford), ‘Jane Austen’s draft gatherings’.

Kathryn Sutherland and Peter Stallybrass concluded the day with a look at manuscript gatherings, considering the different physical forms of blank paper used by writers, from the 16th-century Lope de Vega’s booklets, each neatly holding one act of a play, to the 19th-century notebooks used by Jane Austen. Though blank-paper notebooks had become more common by Austen’s day, the choice of a size of notebook and the use of the pages signified, for both speakers, the self-defined spaces in which these authors drove the pen along in the act of writing.

The symposium was hosted in the library by the Centre for the Study of the Book.