In a previous post, I described how to find digitised magazine archives via Google Books, and I have also previously blogged about newspaper sources available in Oxford, but have not yet written about what American magazines are available here. Following our purchase of three political magazine archives earlier in the year, it seems a good time to rectify that!

In this post:

- Online archives

- Printed and microfilm collections in Oxford

- Finding magazines on SOLO

- Finding articles in magazines

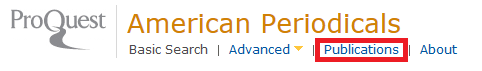

Our major online source for American magazine archives is American Periodicals. This database covers 1740-1943 and contains over 1,500 titles. These magazines are wide-ranging in focus, from political and current affairs titles, to women’s and children’s magazines, literary and scientific journals, and all sorts of other interests. Particular highlights include runs of Benjamin Franklin’s General Magazine, Ladies’ Home Journal, Vanity Fair, The Century Magazine, The Dial, Puck, and McClure’s among many others. Access is available to Oxford users via OxLIP+, on the ProQuest platform. If you are used to using the newspaper archives of the New York Times, Washington Post and others, the search interface will be familiar, and you can cross-search American Periodicals with these newspaper archives. As well as searching for individual articles, you can search and browse the list of titles included by clicking on the ‘publications’ link:

Also available via ProQuest is the complete archive of American Vogue from 1892 to the present, which can again be cross-searched with American Periodicals and the newspaper archives available via ProQuest.

Also available via ProQuest is the complete archive of American Vogue from 1892 to the present, which can again be cross-searched with American Periodicals and the newspaper archives available via ProQuest.

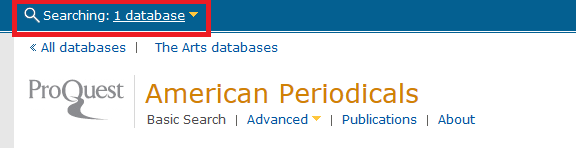

To cross-search ProQuest titles, click on the ‘searching 1 database’ link in the blue bar at the top of the screen. This will open up a list of all the ProQuest databases the Bodleian Libraries subscribe to. You can select as many of these as you like and, on clicking ‘use selected databases’, you will be taken to a generic search screen which will allow you to search across all the ones you chose at once.

As previously mentioned, earlier this year we subscribed to three new online magazine archives: those of The Nation (1865-), National Review (1955-) and The New Republic (1914-). These are three of the most significant American political magazines of the twentieth century (and earlier, in the case of The Nation), covering both sides of the political spectrum. All three are available via OxLIP+ on the EBSCO platform, and as with the ProQuest titles above, can be cross-searched with each other. To do this, click on the ‘choose databases’ link just above the search boxes and, as with ProQuest, you will then be presented with a list of all the EBSCO databases we have access to to select from.

As previously mentioned, earlier this year we subscribed to three new online magazine archives: those of The Nation (1865-), National Review (1955-) and The New Republic (1914-). These are three of the most significant American political magazines of the twentieth century (and earlier, in the case of The Nation), covering both sides of the political spectrum. All three are available via OxLIP+ on the EBSCO platform, and as with the ProQuest titles above, can be cross-searched with each other. To do this, click on the ‘choose databases’ link just above the search boxes and, as with ProQuest, you will then be presented with a list of all the EBSCO databases we have access to to select from.

As well as these three, we also have access to CQ Weekly courtesy of the Rothermere American Institute, directly from their website at http://www.cq.com/displayweekly.do from 1983-. It’s not immediately obvious how to get to the back issues beyond the past few years from their website, but if you go to the advanced search screen you will find that you can search the archives back to 1983.

As well as these three, we also have access to CQ Weekly courtesy of the Rothermere American Institute, directly from their website at http://www.cq.com/displayweekly.do from 1983-. It’s not immediately obvious how to get to the back issues beyond the past few years from their website, but if you go to the advanced search screen you will find that you can search the archives back to 1983.

Other magazine archives can often be found in larger journal collections, such as JSTOR or Periodicals Archive Online, or in odd cases, in various other online collections, for example Commonweal in Literature Online (1992-) or The New Yorker in the Shakespeare Collection from 2002-.

If you are looking for magazines dating from before the 1920s, it’s well worth searching some of the major websites for free digitised materials, such as the Hathi Trust, Internet Archive and the Library of Congress’s American Memory site. You can also find a huge number of 19th century journals in the Making of America sites hosted at Cornell and the University of Michigan.

Alternatively, for recent years, there are a few large databases, mostly business or legal collections, which contain back issues of a surprising number of American magazines:

- ABI/INFORM: The American Enterprise (1994-2006), The American Prospect (1996-), The Atlantic (1986-), Forbes (1992-2006), Foreign Policy (1994-), The New Republic (1988-), Newsweek (1998-2012), Policy Review (1994-2013), The Public Interest (1988-2005), Scientific American (1986-), US News & World Report (2010-), The Washington Monthly (1988-)

- Business Source Complete: The American Enterprise (1994-2006), Bloomberg Businessweek (1996-2010), Forbes (1990-), Foreign Affairs (1964-), Foreign Policy (1990-), Fortune (1992-), The New Republic (1990-), Newsweek (1990-2002), Policy Review (1990-), The Public Interest (1990-2005), Time (1990-), US News & World Report (1990-2010)

- Factiva: Forbes (1992-), Foreign Affairs (1999-), Newsweek (1994-), The New Yorker (2005-), The Weekly Standard (1997-2010)

- Nexis UK: The American Prospect (1992-), The American Spectator (1994-), Bloomberg Businessweek (1975-), The Christian Science Monitor (1980-), Ebony 1984-), Foreign Affairs (1982-), Human Events (2006-), The National Interest (1993-), National Review (1998-), The New Republic (1994-), New York (2005-), Slate (1996-), US News & World Report (1975-), The Weekly Standard (1994-)

- vLex Global: The American Conservative (2007-), The American Prospect (2004-), The American Spectator (2004-), Commonweal (2009-), Human Events (2009-), Mother Jones (2004-), The National Interest (1993-), Policy Review (2004-), The Progressive (1993-), Reason (1993-), Saturday Evening Post (1984-)

All of these databases may be found via OxLIP+ and there should be records on SOLO for the individual titles as well. Note that these archives may not be comprehensive and in most cases, are not digitised versions of the print issues but just provide access to the text of the articles.

Printed and microfilm collections in Oxford

As well as the various online archives, there are a lot of American magazines available in print or on microfilm in the Vere Harmsworth, Bodleian, or other Oxford libraries. Several key titles are listed in the newspapers section of our online guide, and below I’ve listed a selection of titles where Oxford has a more extensive run available in print or on microfilm than may be found online through one of the archives above. Note that for some titles, the Bodleian holds the European or International edition rather than the US one; this should be indicated in the record on SOLO.

- The American Enterprise: VHL 1990-2000, Nuffield 1990-1998. Previous title was Public Opinion, held in Nuffield 1978-1988. Also available online via ABI/INFORM and Business Source Complete from 1994-2006.

- The Atlantic/The Atlantic Monthly: Bodleian 1857- (not necessarily complete). Title changes frequently so there are many records on SOLO. Also available online via Making of America (1857-1901), ABI/INFORM (1986-)

- Collier’s/Collier’s Weekly/Collier’s Once a Week: Bodleian 1889-1890, 1902, 1905-1919

- Commonweal: Bodleian 1947-1991. Also available online via Literature Online 1992- and vLex Global 2009-.

- The Christian Science Monitor: Radcliffe Science Library 1975-2000, 2005-. Also available online via Nexis UK 1980-.

- Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report/CQ Weekly: VHL 1953-2007. Also available online via cq.com 1983-.

- Dissent: Bodleian 1954-1980, Social Science Library 1981-

- Ebony: VHL 1958-2008. Also available online via Nexis UK 1984- and Google Books 1959-2008.

- Fortune: Bodleian 1930-1943, 1953-1959, 1963-1978. Also available online via Business Source Complete 1992-.

- Harper’s/Harper’s Magazine/Harper’s Monthly Magazine/Harper’s New Monthly Magazine: Bodleian 1880-, English Faculty Library 1880-1903, 1908-1909. Also available online via Making of America 1850-1899 and the Hathi Trust (various 19th century volumes).

- Harper’s Weekly: VHL 1861-1865

- Life: Bodleian 1936-1938, 1944-1955. Also available online via Google Books 1953-1972.

- Monthly Review: Social Science Library 1965-2002, 2004-

- The National Interest: VHL 1985-. Also available online via Nexis UK and vLex Global 1993-.

- National Journal: VHL 1977-

- Newsweek/News-week: Bodleian 1949-. Also available via Nexis UK 1975-, Business Source Complete 1990-2012, Factiva 1994- and ABI/INFORM 1998-2012.

- New York: VHL 1969-1970. Available online via Google Books 1975-1997 and Nexis UK 2005-.

- New York Review of Books: Bodleian (Lower Gladstone Link) 1963-, English Faculty Library 1968-1976, 1994-, VHL 2007-

- The New Yorker: Bodleian 1925-. Also available online via the Shakespeare Collection 2002- and Factiva 2005-.

- Political Affairs/The Communist/The New Masses/The Liberator/The Masses: Bodleian 1911-2008

- The Progressive/Follette’s Magazine/La Follette’s: VHL 1948-1982

- Rolling Stone: Bodleian 1971-1976

- Saturday Evening Post: Bodleian 1900-1963. Also available online via American Periodicals 1821-1830, 1836-1885 and vLex Global 1984-.

- Time: Bodleian 1943-. Also available online via Business Source Complete 1990-.

- US News & World Report/United States News: VHL 1940-2010. Also available online via Nexis UK 1975-, Business Source Complete 1990-2010 and ABI/INFORM 2010-.

In addition to these, we also have a specific collection of African American magazines from the early to mid 20th century. These are available as microfiche/films in the VHL (shelfmarks Micr. USA 397-422) and include: African: a Journal of African Affairs (1937-1948), Alexander’s Magazine (1905-1909), The Brown American (1936-1945), Color Line (1946-1947), The Colored American Magazine (1900-1901), Competitor (1920-1921), Crisis (1910-1940), Fire!! (1926), Half-Century Magazine (1916-1925), Harlem Quarterly (1949-1950), Messenger (1917-1928), The National Negro Voice (1941), Negro Educational Review (1950-1965), Negro Farmer and Messenger (1914-1918), Negro Music Journal (1902-1903), The Negro Needs Education (1935-1936), The Negro Quarterly (1942-1943), Negro Story (1944-1946), New Challenge (1934, 1937), Quarterly Review of Higher Education Among Negroes (1933-1960), Race (1935-1936), The Southern Frontier (1940-1945), The Tuskegee Messenger (1924-1936) and The Voice of the Negro (1904-1907).

It can be tricky to find magazines on SOLO if you’re not sure exactly what you’re looking for, particularly if they have relatively generic titles such as Time or The Nation. Titles often change at various points in a magazine’s history which adds a further layer of complication. There are a couple of things you can do which can help you when searching SOLO for any given magazine:

- Use the limit your search filter under the main search box to restrict your search to journals.

- Check the date ranges carefully in the record. Note that the dates given will be for that specific title; if the journal you are looking for changed its title, even slightly, there will be a new record on SOLO for each time it does. The way to find this out is to look in the details tab of the record where you will see previous/subsequent titles listed as related titles. Unfortunately these aren’t links that you can then click on, but it will at least tell you what you need to search for!

Here’s a screenshot for a search for The Atlantic Monthly which illustrates these points. This is a particularly extreme example of title changes resulting in multiple records!

Finding the magazines themselves is all very well, but particularly for those which are only available in print or microfilm, it can be a time-consuming process to work through indexes and tables of contents hunting for articles you might be interested in. One key resource to help you locate articles in American magazines and journals is the Readers’ Guide. This has been published since 1901 (with coverage back to 1890) and indexes articles in a huge number of American magazines and journals by subject. We have the printed volumes available in the library from 1900-1969, and also have access to the fully searchable online version which covers 1890-1982. You can get to this via OxLIP+, and when you click through, the search interface will look familiar if you are used to using either America: History & Life or the archives of The Nation, National Review and The New Republic as it is also provided by EBSCO. This means that the Readers’ Guide can be cross-searched with these if you follow the instructions above, and it will also provide access to the full text of articles in those three magazine archives, as well as some other titles it indexes.

When searching the Readers’ Guide, there are several useful features that can help you narrow down your results and find the articles you need. You can limit your results to those where the full text is available, or filter them to see articles from magazines or academic journals or other types of publication. You can also filter by individual publication itself, which can be helpful if you know what magazines are available to you here in Oxford. Any of these can be done pre- or post-searching (see screenshots below). And even if the articles you want are not available in full text within the database, you can use the Find it @ Oxford button next to any record to click through to see if that article is available to you via another means, such as one of the other online collections, or kick off a search in SOLO to look for the print.