The Bodleian Libraries hold a rich and varied collection of papers related to the Edgeworth family from the 17th to the 19th century. Only a tiny percentage of the material contained therein is available in print and even less has been subject to scholarly editing.

The collection may be little known, but it is of great significance, providing vital evidence (manuscript drafts and correspondence) about the literary career of one of the most important novelists of the early 19th century, Maria Edgeworth (1768-1849). Maria’s work is also placed in context by additional documentation that covers the educational, agricultural and political theory and practice of her father, the politician, writer and inventor Richard Lovell Edgeworth (1744-1817).

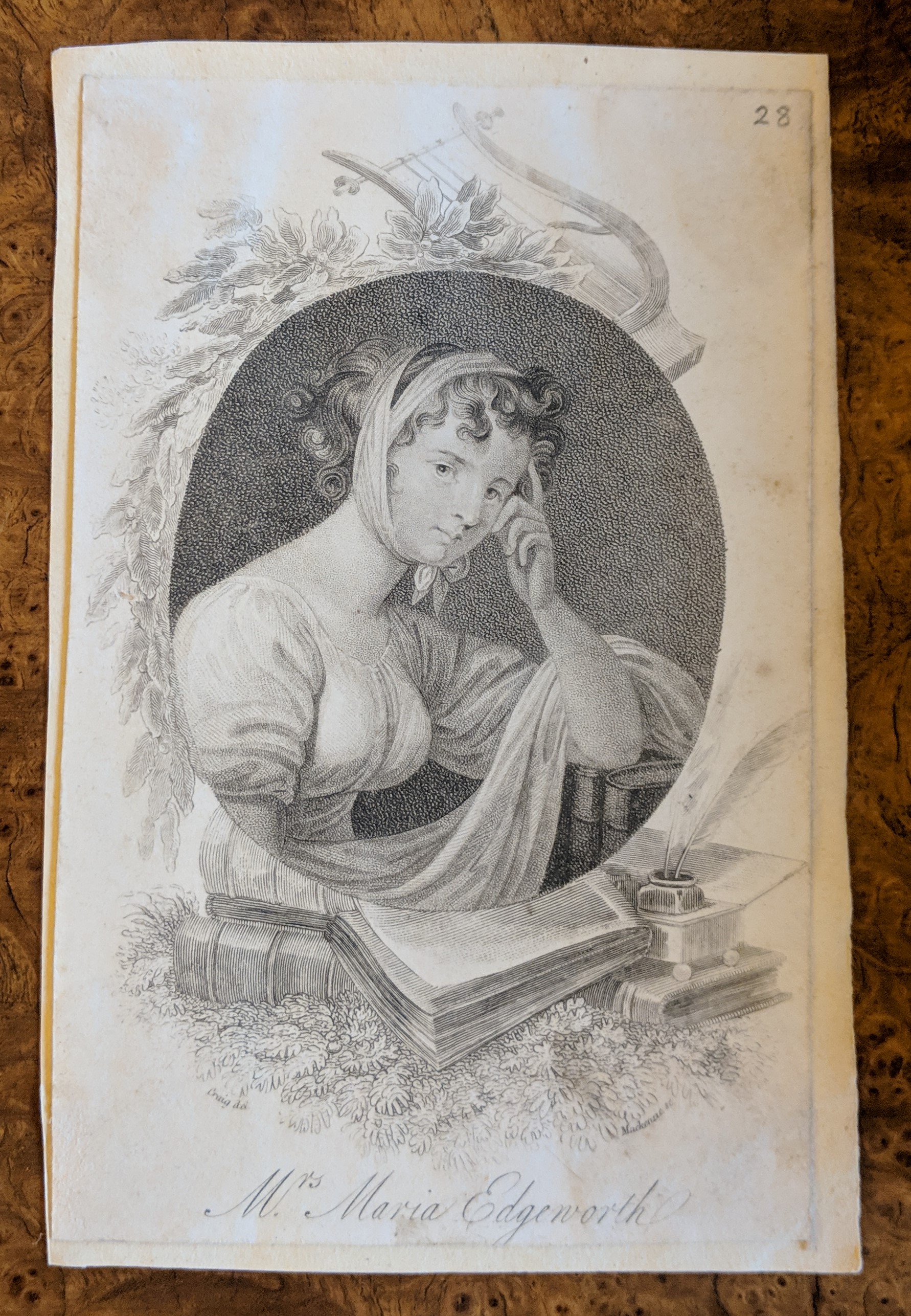

Engraving of Maria Edgeworth (MS. Eng. misc. c. 901, fol. 28).

Through assorted written material, the collection shows the ways in which an extended family with connections in Ireland, England, France and India, communicated and collaborated in the production of art, literature, and scientific knowledge. And it sheds light on Anglo-Irish relations during a period of political contestation and transformation.

Over the next 12 months we will investigate ways of raising the profile of this collection through social media, scholarly and digital editing. The project takes one selection of the material in the Edgeworth papers— correspondence and other evidence related to the year 1819-1820— and tracks it alongside 2019-2020, a momentous period in the history of the relations between Britain and Europe. Each month, our blog will present sample documents from the same month 200 years earlier. Writing in March 2019, as the UK faces huge political upheaval, let us introduce you to Maria and her family, who in March 1819 are in the midst of a personal – rather than political – challenge on both sides of the Irish Sea.

Love and Marriage: A Family Affair

As the old song says, love and marriage go together like a horse and carriage. But in the early 19th century, ‘love’ wasn’t the key concern. The idea of the ‘marriage market’ brings home the financial considerations of matrimony in the period. For women, this was particularly acute. The financial and legal implications of an imprudent marriage were serious – it was, after all, impossible to get a divorce without first obtaining a private Act of Parliament.

It is no wonder families were so invested in securing the right matches for their children – and no surprise that so many novels dramatised the intrigues, concerns and implications of the marriage market in the ‘courtship plot’. Lady Russell in Jane Austen’s Persuasion (1818), for example, convinces heroine Anne Elliot not to marry the nobody Frederick Wentworth as this would present too much of a social risk. When Wentworth returns a Captain, Lady Russell’s opposition comes across as snobbish and intrusive. In the context of 19th-century marriage laws and women’s rights, Lady Russell’s concern is sincere. Today marriage comes under the umbrella of ‘personal relationships’, but 200 years ago matrimony was very much a family affair.

In March 1819, bestselling novelist Maria Edgeworth was embroiled in her own family affair that could have come straight from a novel like Persuasion. Her young half-sister, Fanny, some 30 years Maria’s junior, was being courted by a man whose morals her family admired but whose personality they considered rather dull: the ‘Mr. L.W.’ [Lestock Wilson] of 31 Harley Street. Fanny, Maria and another half-sister, Honora (1791-1858) who was only eight years older than Fanny, were visiting London together. Maria hurriedly wrote home to Edgworthstown, Ireland, to her step-mother– and Fanny’s mother – Frances Ann Beaufort (1769–1865), her ‘dearest mother’ (in fact one year younger than Maria herself) – to discuss what to do. Believing Mr LW to be unsuitable, Maria sought to dazzle Fanny by opening the country-educated girl to the best of London society. She had herself refused a proposal of marriage in 1802 from the Swedish intellectual, Abraham Niclas Clewberg-Edelcrantz (1754-1821), who she met on a family visit to Paris, lacking the confidence to leave the family she loved so dearly for an uncertain union.

Drawing of Fanny Edgeworth as a young child by her mother Frances Edgeworth (MS. Eng. misc. c. 901, fol. 8).

Drawing of Fanny Edgeworth as a young adult by her mother Frances Edgeworth (MS. Eng. misc. c. 901, fol. 9).

The urgent tone of this letter bespeaks the need to act quickly and decisively. Both Maria and Frances are wary of Fanny accepting the invitation to Mr LW’s house, though she was desirous to ‘see & judge for herself’. Despite LW’s protestations that ‘he would not behave to her as a lover or pay her any peculiar attention’, such a visit would be ill-advised: as Maria contends, it would be neither ‘prudent’ nor ‘proper’.

Letter from Maria Edgeworth to Frances Edgeworth (MS. Eng. lett. d. 696, fol. 146r).

Letter from Maria Edgeworth to Frances Edgeworth (MS. Eng. lett. d. 696, fol. 146v).

Letter from Maria Edgeworth to Frances Edgeworth (MS. Eng. lett. d. 696, fol. 147r).

Letter from Maria Edgeworth to Frances Edgeworth (MS. Eng. lett. d. 696, fol. 147v).

Maria’s concern is that a strong romantic inclination may not be sufficient to ‘secure Fanny’s permanent happiness’. Admittedly, Maria does not relish her ‘Duenna’ (chaperone) role, but writes that ‘this is to me as a feather in the balance compared with the object in view’. Convinced of Mr LW’s unsuitability, the Edgeworths sought to protect Fanny from a marriage that she wouldn’t be able to leave. The following month, Fanny refused him – but she regretted and mourned her decision, accepting his renewed proposal some ten years later.

This letter also gives us an insight into the complex generational dynamics of the Edgeworth family. Maria’s father, Richard Lovell Edgeworth, married four times and had 22 children. Richard’s death two years before these events left Maria and his fourth wife, Frances, to direct the family drama. Maria takes on her father’s mantle (she’d had early experience in helping him manage his family estate) and adopts a paternal role in agreeing with Fanny’s mother the best way forward.

Transcript of letter:

Dearest mother On our return from breakfasting with M.rs Marcet (where we met M.r Mallet) our packet of letters was put into our hands & we ran to our own fireside to devour the con – Lest I should not have time to say more let me make sure of the most important thing I have to say. That I entirely agree with you that it would neither be prudent in her present cir=cumstances nor proper in the eyes of the world for Fanny to part company from me to go even for a few days alone to 31 Harley St.t – This having been my opinion before I knew it was yours and being streng=thened by the decided expressions In your letter to Fanny just rec.d I have advised her by no means to go there alone till at least till we hear again from you – She will or has told you what passed between M.r L W and her yesterday morning – in consequence of his promise that if she were in the house with him he would not behave to her as a lover or pay her any peculiar attention she wished to spend some days at Harley S.t without Honora or me that she might see & judge for herself.

When I told her my reasons against this – & in particular stated repeated to her the advice my father gave me not to trust myself alone with a man in whose favor my inclinations spoke more than my judgment Fanny most prudently & kindly has yielded to me her wish & says she is quite convinced by my reasons & therefore was unwilling to write to ask your opinion further – that is to ask you whether in consequence of [what] has since passed between her & L W the circumstances are so far altered that you would advise her to go there by her=self – They have but one small spare room & therefore F — ^anny^ says cannot ask us to be with her but that objection c.d I think be easily waived for I don’t care into what space I am crammed – I can sleep in the bed with her – Honora could for a week & would I am sure go to Sneyd – We cannot all have at every moment what is most agreeable But Honora I am sure would be as willing as I am to do what may not be agreeable for the time to secure Fanny’s permannent happiness – You may guess how disagreeable it will be to thrust myself into a house Duenna=ways – the maiden’s steps to haunt & in society that cannot relish me at any time – but [xxx] this is to me as a feather In the balance compared with the object in view –

I advise that she should remain with me to the end of the fortnight at Lady E W’s – that she sh.d dine then go with me to M.rs Carr’s Hampstead or M.rs Baillie’s or wherever we next deter=mine to go for another week or so – and then if the Wilsons ask me to go with her to Harley S.t I am ready to go if you approve & to stay as long or as short a time as Fanny wishes.

Answer me very distinctly and decidedly my dearest friend these Questions Do you approve of my going with F to 31 Harley S.t to stay some time – or Do you approve or not of Fanny’s going there by herself – I cannot write or think on any other subject at present

truly affectionately yrs,

Maria E

The blended Edgeworth clan – consisting of several step-mothers, numerous half-siblings – provided a whole series of domestic dramas, revealing surprising alliances, deep loyalties and often lively comedy. Over the next 12 months we look forward to opening the Edgeworth papers, uncovering their stories, and sharing them with you.

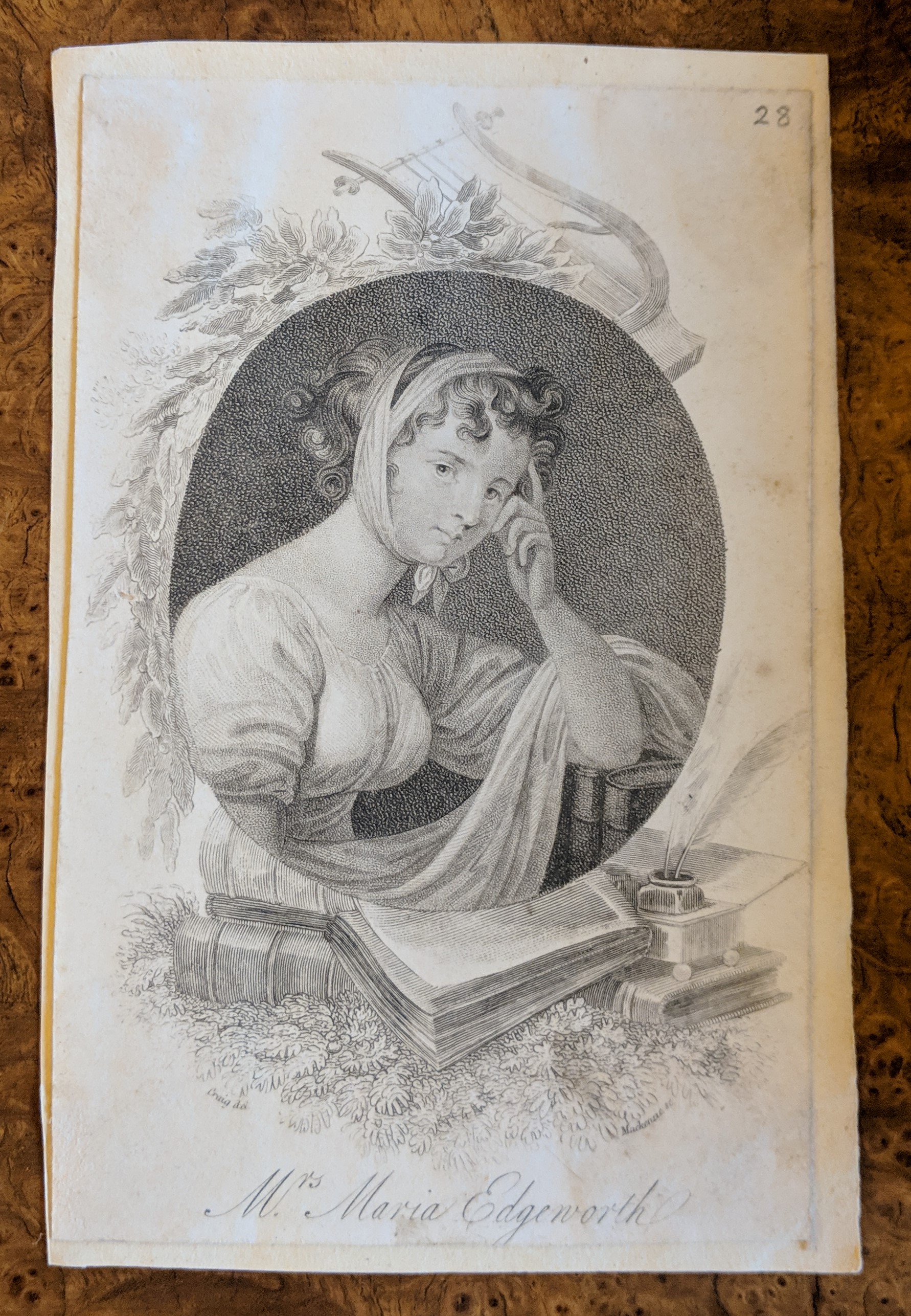

Opening the Edgeworth Papers: the team

Ros Ballaster, Professor of Eighteenth-Century Studies, Faculty of English and Mansfield College, University of Oxford

Catriona Cannon, Deputy Librarian and Keeper of Collections, Bodleian Library

Anna Senkiw, Research Assistant

Ben Wilkinson-Turnbull, Research Assistant

Follow us on Twitter @EdgeworthPapers

![Digitised copy of 'Warning', from Jenny Joseph's poetry notebooks [MS. 12404/41]](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/archivesandmanuscripts/wp-content/uploads/sites/161/2021/07/Warning.jpg)

OED chatelaine: ‘an ornamental appendage worn by ladies at their waist … consists of a number of short chains attached to the girdle or belt … bearing articles of household use and ornament, as keys, corkscrews, scissors, penknife, pin-cushion, thimble-case, watch etc …’

OED chatelaine: ‘an ornamental appendage worn by ladies at their waist … consists of a number of short chains attached to the girdle or belt … bearing articles of household use and ornament, as keys, corkscrews, scissors, penknife, pin-cushion, thimble-case, watch etc …’