Each January the Archive of the Conservative Party releases files which were previously closed under the 30-year rule. This year, files from 1993 are newly-available to access.

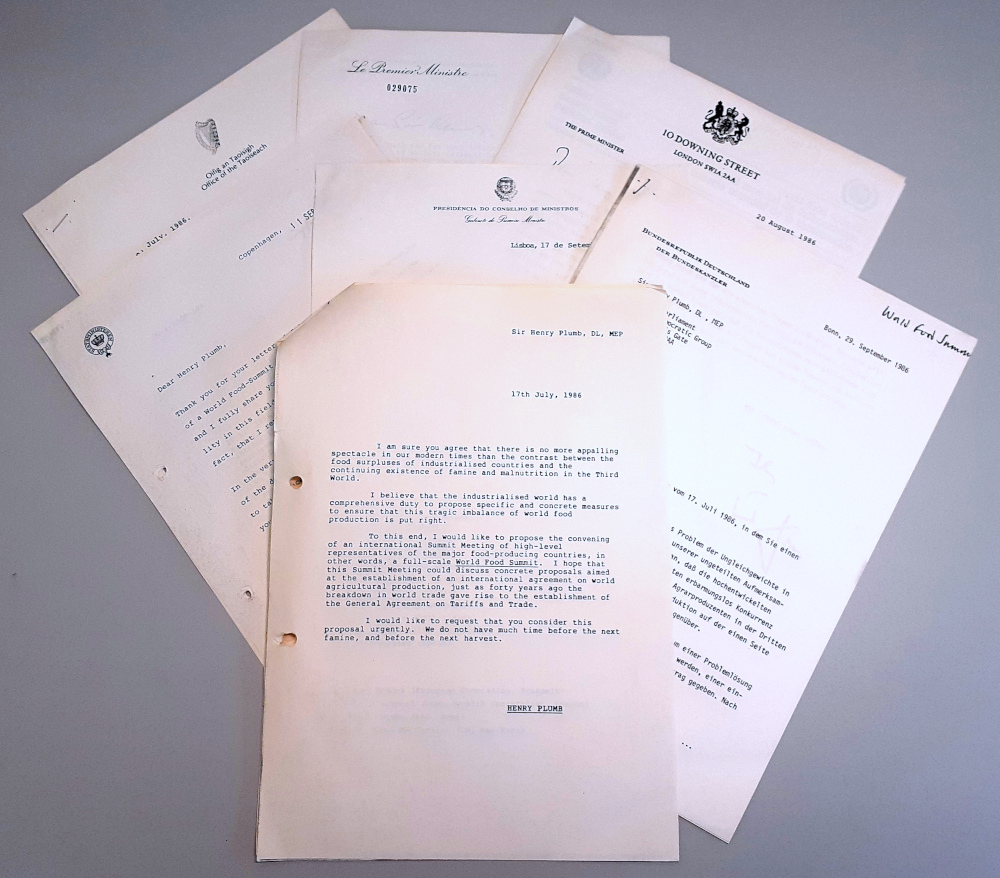

Despite the recession of the previous couple of years coming to an end, John Major’s third year as Prime Minister was dominated by internal Party conflict over Europe and low public popularity, manifesting in two significant by-election defeats. These issues are amongst those covered within the newly-released files for 2024, alongside subject files and briefs from Conservative Research Department (CRD), material of the Young Conservatives and Conservative student organisations, and correspondence and subject files of Conservatives in the European Parliament. This blog post will highlight some of the material included in this year’s newly-available files, with a full list linked at the end.

Europe and the Maastricht Treaty

In early 1992, European leaders signed the Maastricht Treaty to bring greater unity and integration between the countries of the European Economic Committee, creating the European Union. The Treaty officially became effective on 1 November 1993 once each county had ratified it, following referendums in Denmark, France, and Ireland. Whilst no referendum was held in the UK, the Maastricht Treaty did bring divisions to Parliament, especially the Conservative Party. A small number of Eurosceptic Conservative MPs voted with the opposition, who opposed the decision to opt out of the ‘Social Chapter’ rather than the Treaty itself, against ratification. Combined, these MPs were able to defeat the implementation of the Treaty in a series of votes due to the small Conservative majority at the time. Whilst Tory rebels failed in their campaign for a referendum, and Parliament did eventually ratify the Treaty, this happened only after John Major called a confidence motion in his own government. The issue of Europe, and the internal divisions it caused, undoubtedly defined Major’s early years as Prime Minister.

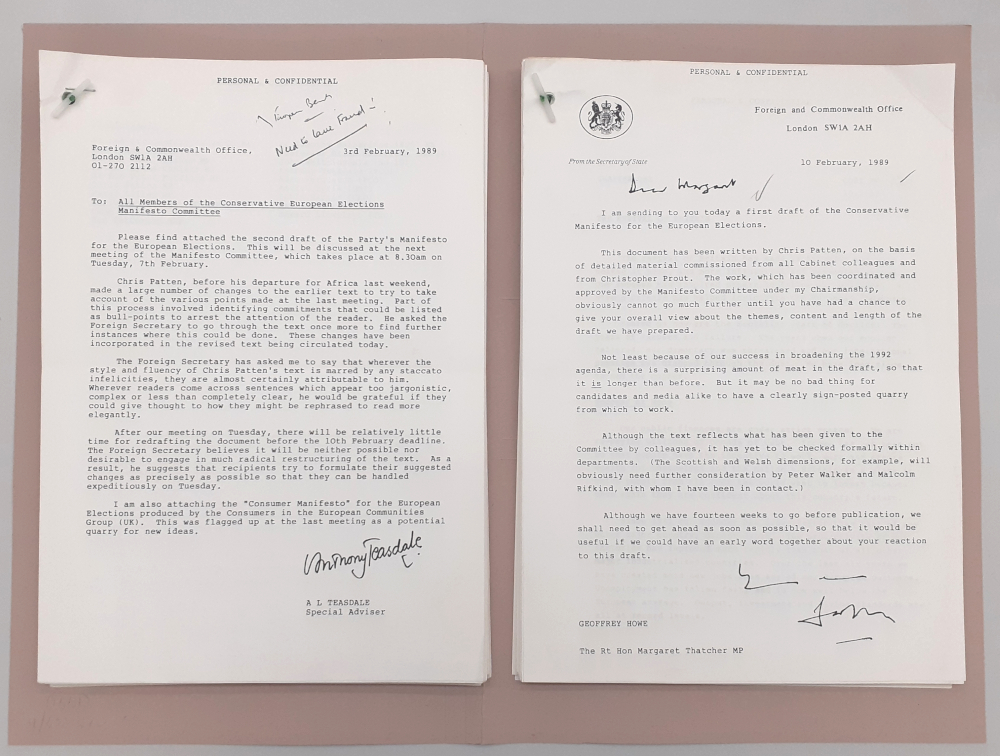

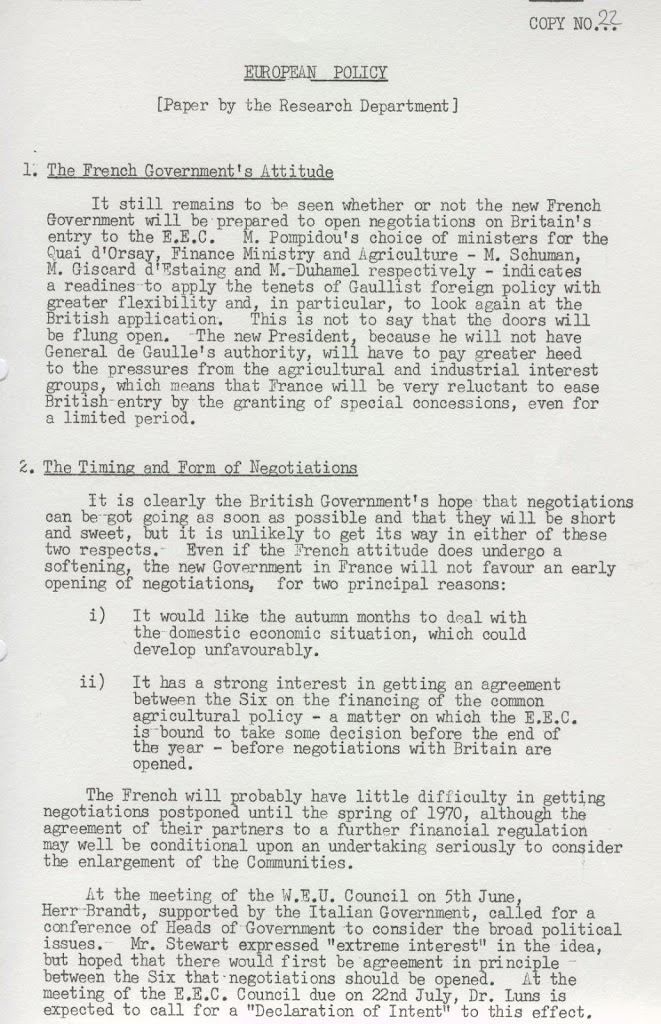

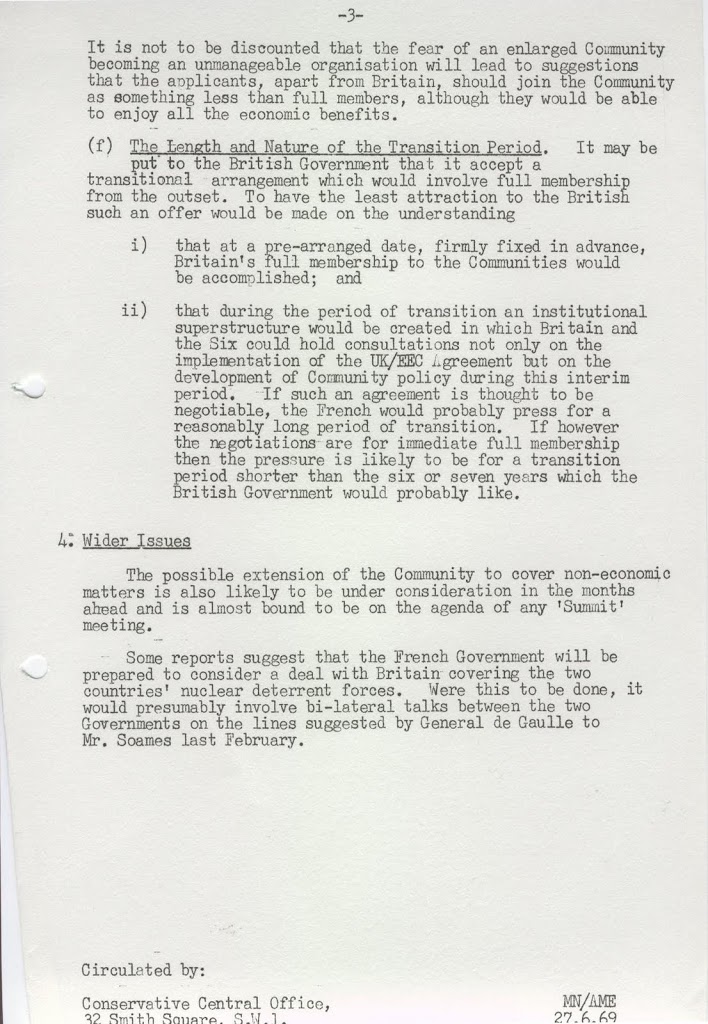

Many of this year’s newly-released files offer an insight into the way the Conservative Party viewed and approached the issue of the Maastricht Treaty, especially the debate over whether to hold a referendum. These can be found primarily in the collections of Conservatives in the European Parliament, CCO 508, and Conservative Overseas Bureau/International Office, COB. The image below shows two documents relating to the question of a referendum. The House of Commons Library Research Paper (left) provides details on the background to the Treaty and the arguments on either side of the debate, whilst the CRD brief of May 1993 (right) lists arguments against a referendum. These include the fact that the House of Commons had firmly defeated a vote on the issue, and that a well-publicised telephone referendum, ‘Dial for Democracy’, had received a poor turnout, suggesting limited public interest in the Treaty.

Newbury and Christchurch by-elections

Internal Party divisions over Europe, alongside slow economic recovery, resulted in the Conservative Party suffering a couple of significant by-election defeats in 1993. The Party lost two seats, Newbury and Christchurch, which they had won by substantial majorities in the 1992 General Election. The Newbury by-election, held on 6 May, saw a swing of 28.4% to the Liberal Democrats, the Conservative Party losing this seat for the first time since 1923. Only two months later, the Christchurch by-election of 29 July saw an even higher swing of 35.4% to the Liberal Democrats.

This year’s newly-available files contain much material relating to these by-elections, including detailed constituency profiles, briefings, memoranda, and analyses of results. The following images show examples of the ‘lines to take’ created by CRD in the lead-up to these elections. Notably, whilst the Newbury by-election offered two options: ‘The Conservatives hold Newbury’ or ‘The Liberal Democrats take Newbury’, the later Christchurch election included an additional defeat option, allowing for either ‘Tories lose by less than 12,000’ or ‘Tories lose by more than 15,000’. Evidently, expectations had fallen. Whilst the Party won back Christchurch in the 1997 General Election, Newbury remained Liberal Democrat until 2005, illustrating misplaced confidence in the assertion that ‘come the next election, Newbury will return a Conservative candidate’ (CPA CRD 5/21/13).

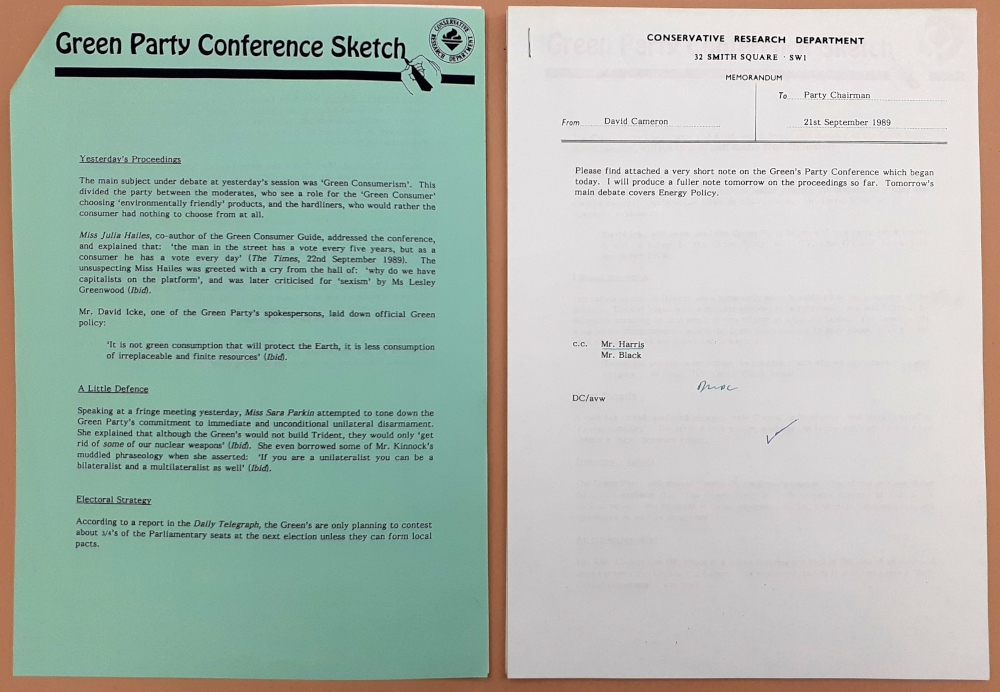

Conservative student organisations

Amongst the material being released this year are several files of both the Young Conservatives and Conservative Party student organisations, including the Conservative Collegiate Forum (CCF), also known as Conservative Students. Alongside the addition of these new files from 1993, the collection of Conservative Student Organisations, CCO 506/D, has recently been updated and expanded, offering a valuable insight into the political activities of Conservative students throughout the late 20th century. Files being released this year include assorted meeting minutes, conference papers, campaigning and publicity material, and research files. A significant amount of the material within this collection relates to the CCF’s campaign for voluntary membership of NUS (National Union of Students), a campaign which occupied much of their time and resources. The image below illustrates a couple of examples of the briefings and reports created by CCF during the late 1980s and early 1990s as they monitored and documented various student union ‘abuses’ perceived as evidence that student union reform, in general, was needed.

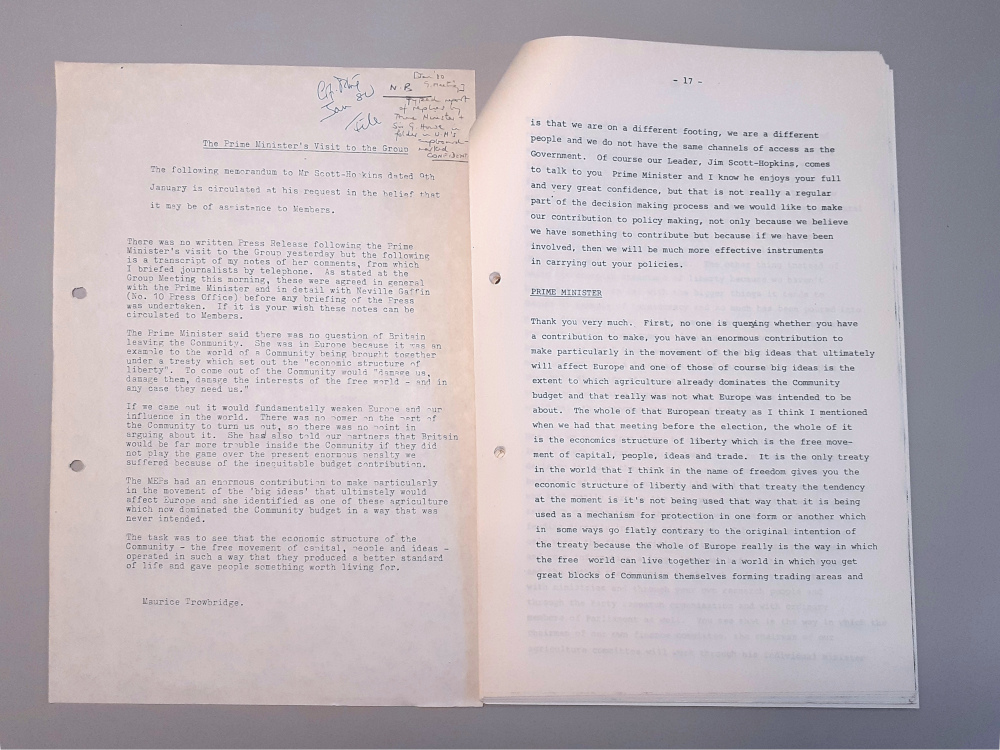

Rachel Whetstone, Conservative Research Department

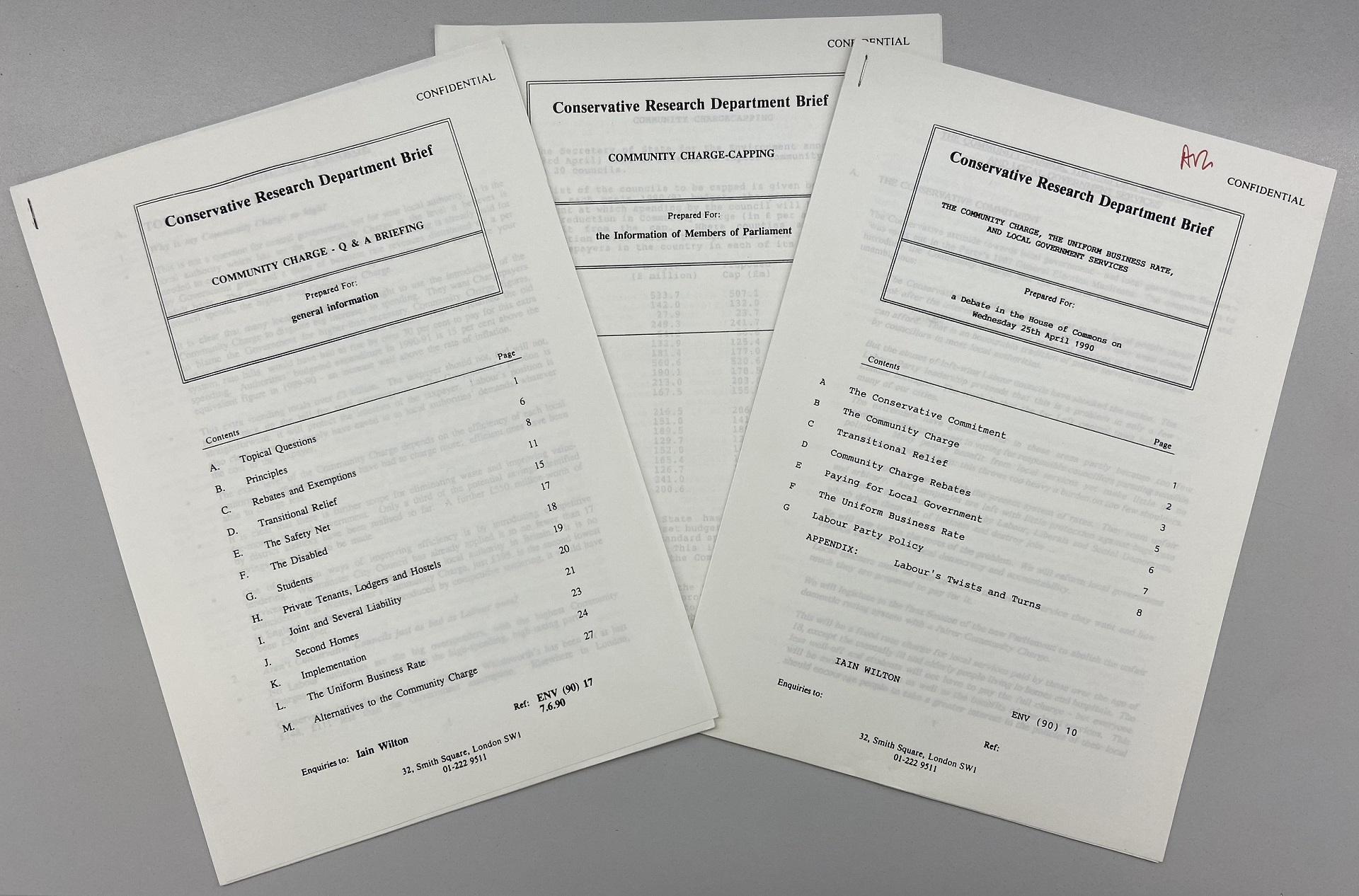

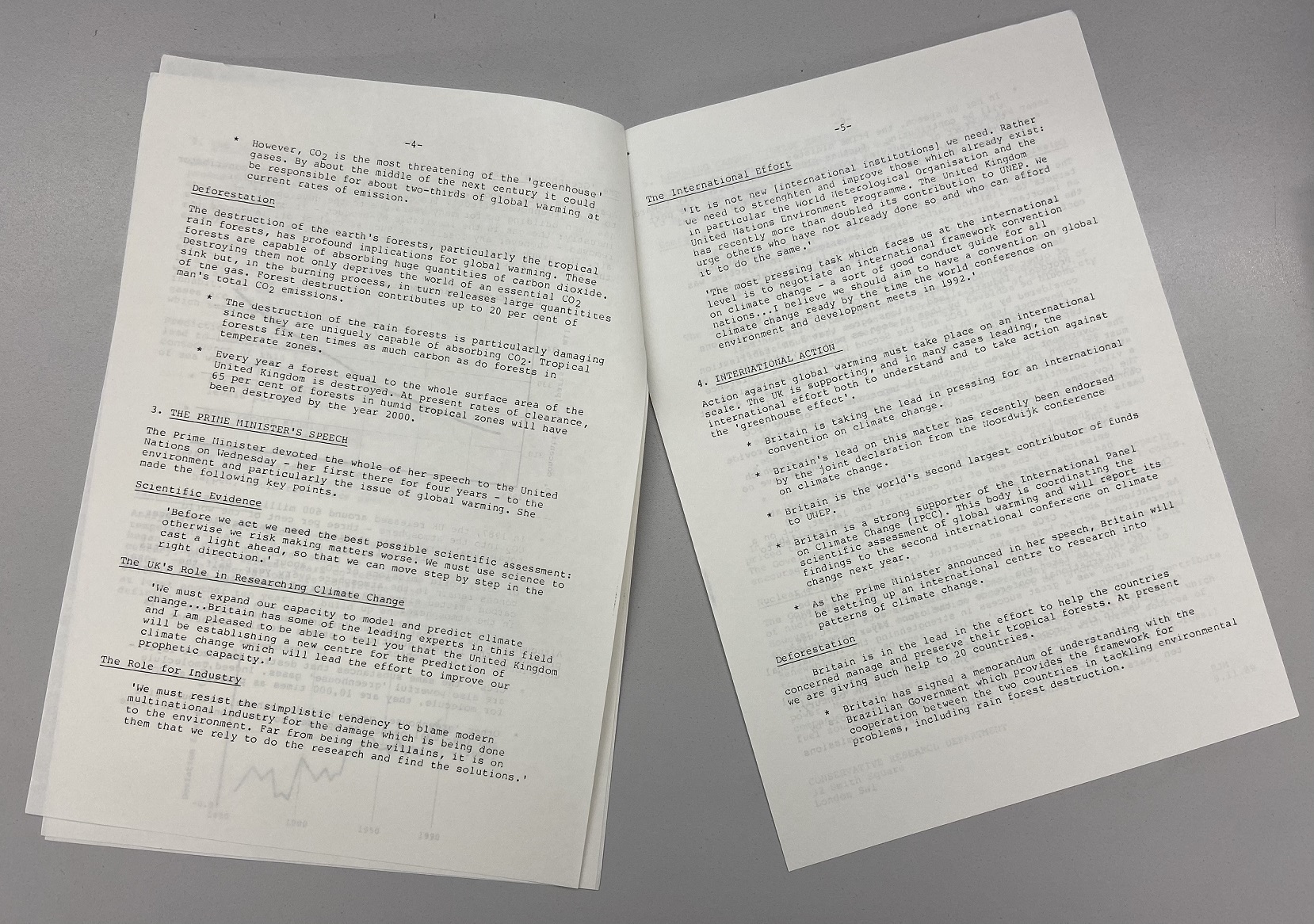

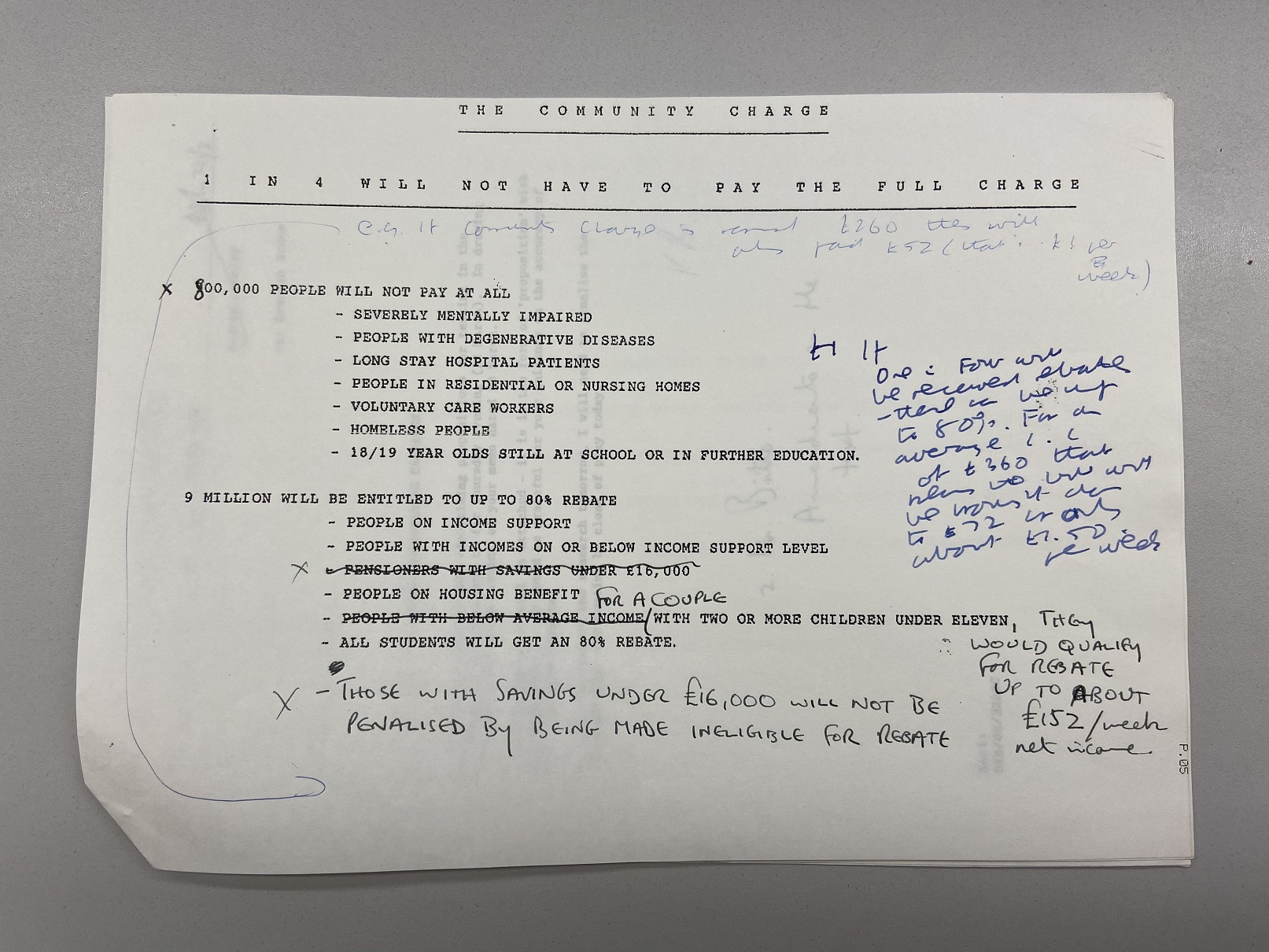

Lastly, as in previous years, files of CRD, including subject files, briefs, and desk officers’ letter books, comprise a significant proportion of the newly-released files for 2024. Amongst these are a handful of letter books of Rachel Whetstone, head of CRD’s political section between 1992 and 1993. These offer an insight into the campaigning techniques and opposition monitoring carried out by CRD at this time. The image below shows a memorandum from Julian Lewis, CRD Deputy Director, outlining campaigning methods. Lewis argues in favour of negative campaigning, suggesting ‘We did not win the General Election – Mr Kinnock’s Labour Party lost it, largely as a result of the ‘fear factor’ which we and others had helped generate’ (CPA CRD/L/5/24/8).

All the material featured in this blog post will be available from 2 Jan 2024. The full list of de-restricted items can be accessed here: Files de-restricted on 2024-01-02

The CRD catalogue is currently being updated and will be available shortly. In the meantime, if you wish to access any of the newly-available CRD files, please email conservative.archives@bodleian.ox.ac.uk

![Image shows interior pages of the Conservative Party European Election Manifesto 2014. [Reference: CPA PUB 332/8].](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/archivesandmanuscripts/wp-content/uploads/sites/161/2020/02/PUB-332-8-last-manifesto.jpg)

![Image shows the election address and campaign ephemera of Chistopher Prout, Leader of the Conservatives in the European Parliament, at the 1989 European Elections. [Reference: CPA PUB 581/3/4/7].](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/archivesandmanuscripts/wp-content/uploads/sites/161/2020/02/PUB-581-3-4-7-Prout-87-address.jpg)