On 20th November the Bodleian Libraries hosted a workshop on ‘The Archives and Records of Humanitarian Organisations: Challenges and Opportunities’. The event was attended by archivists, curators and academics working within the field of humanitarian archives and I was pleased to be invited along to learn more about their work and write a blogpost about some of my observations.

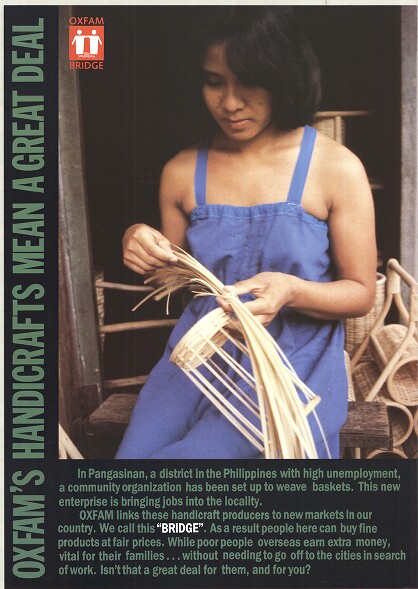

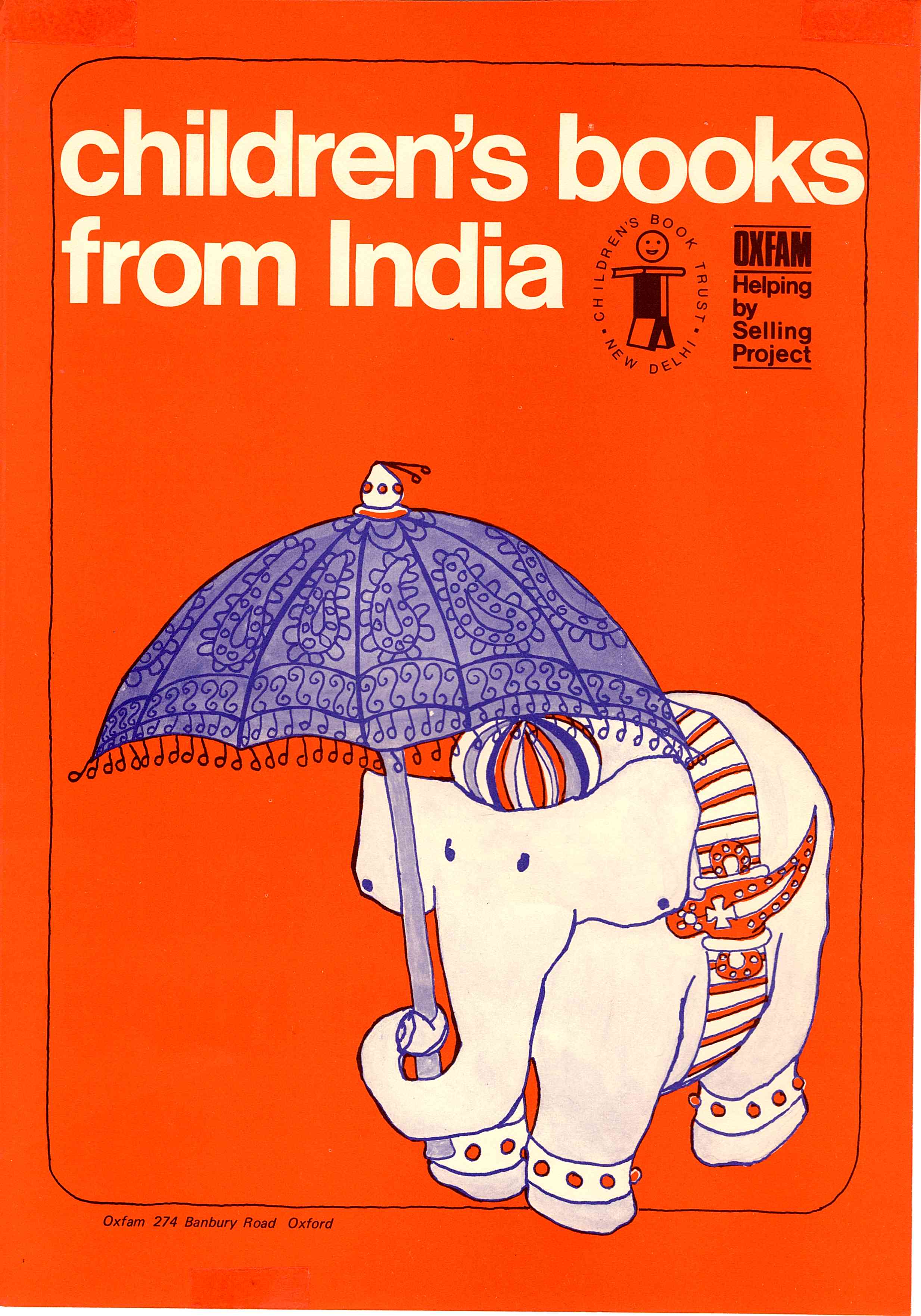

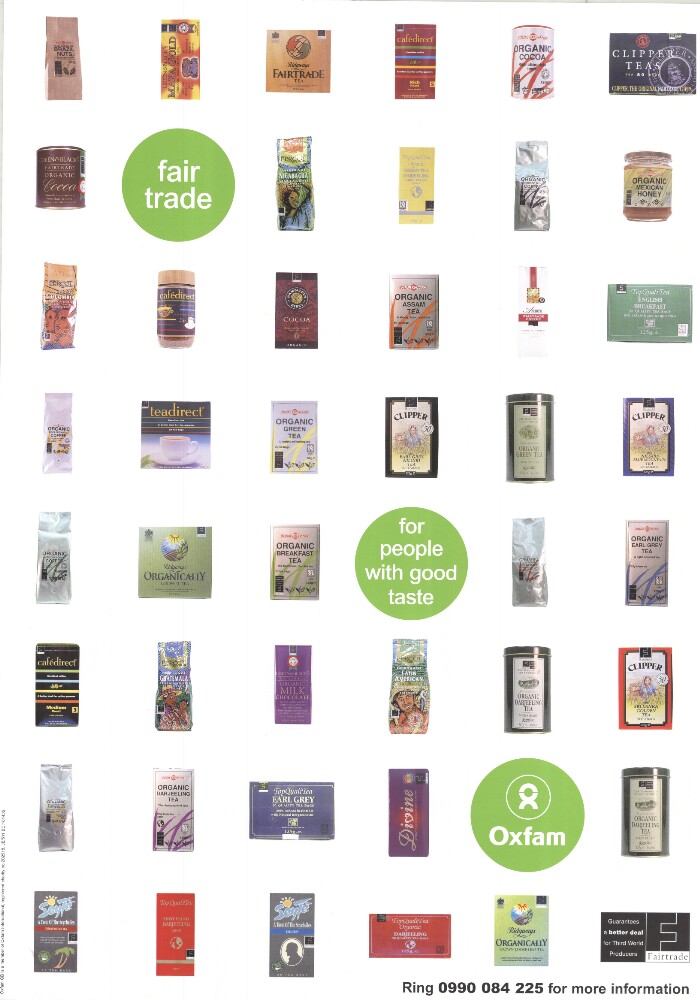

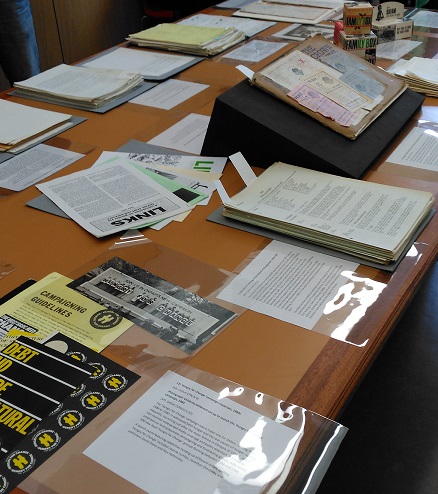

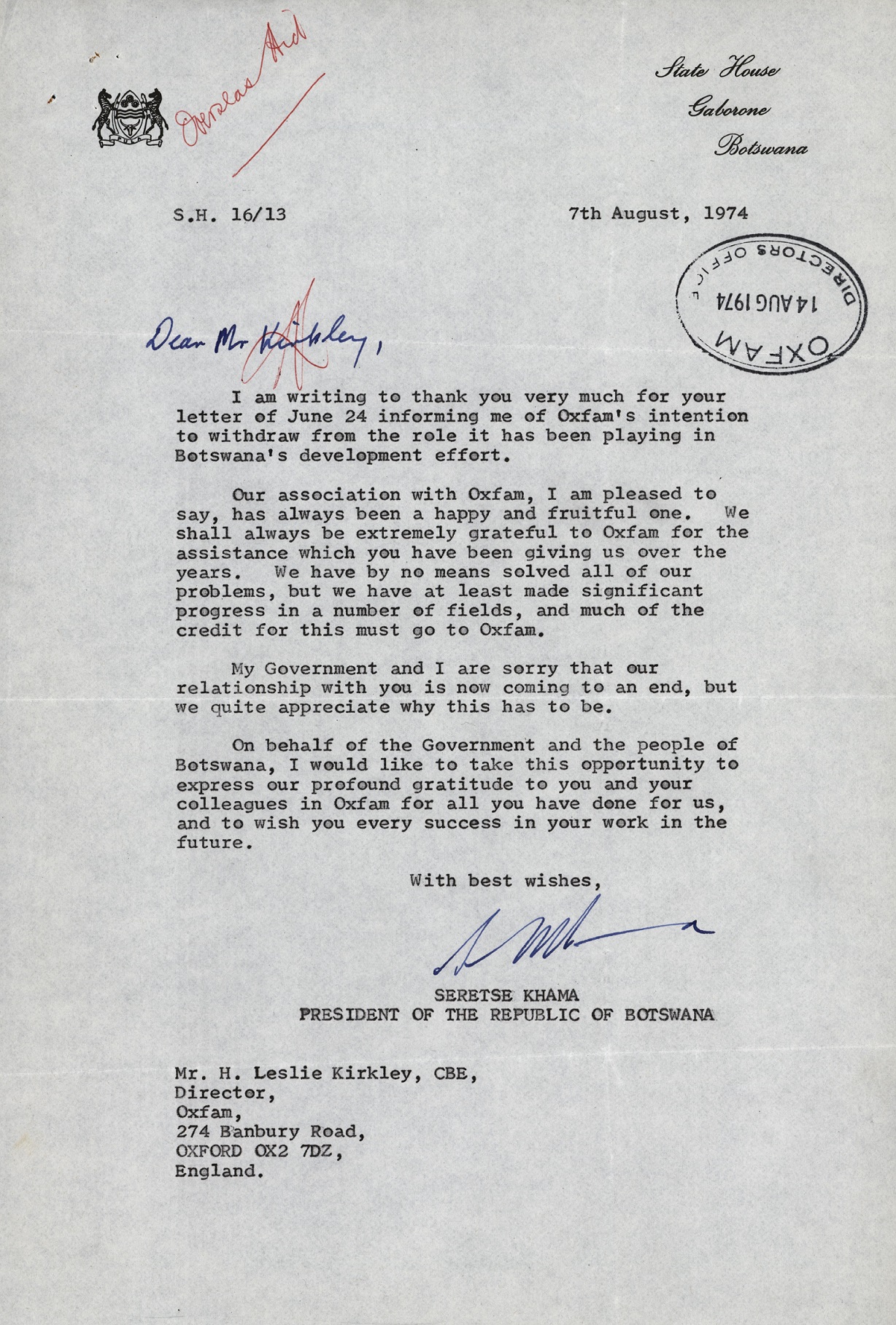

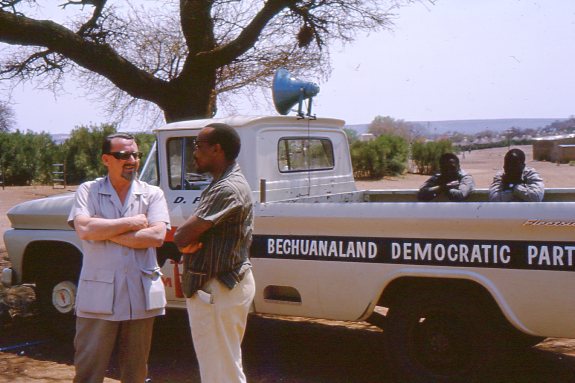

The first talk was given by Chrissie Webb, Project Archivist at the Bodleian Libraries, who discussed her work on the archive of the international charity, Oxfam. The archive was donated to the Bodleian in 2012 and constitutes an enormous collection of over 10,000 boxes of material. Chrissie explained that the archive mostly consists of written documents, but also contains objects and ephemera, audio recordings and digital materials. Cataloguing the archive took several years and was funded by a grant from the Wellcome Trust, as the materials are of great interest to those studying the history of health and public policy, humanitarianism and the voluntary sector. Chrissie touched on a number of issues in her talk, particularly highlighting the challenges of appraising and arranging a collection of such size in sufficient detail. As a trainee the principles of arrangement are still quite new to me, so the idea of working on a collection so big is extremely daunting! The work required robust workflows and proved useful as a case study for development of the Bodleian Libraries appraisal guidelines for future collections. Chrissie also highlighted that the Oxfam catalogue was published on a rolling basis to allow the Libraries to promote the collection and prevent an end-of-project information dump of epic proportions. If you’re curious to learn more, the Oxfam archive can be explored via Bodleian Archives & Manuscripts: https://archives.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/

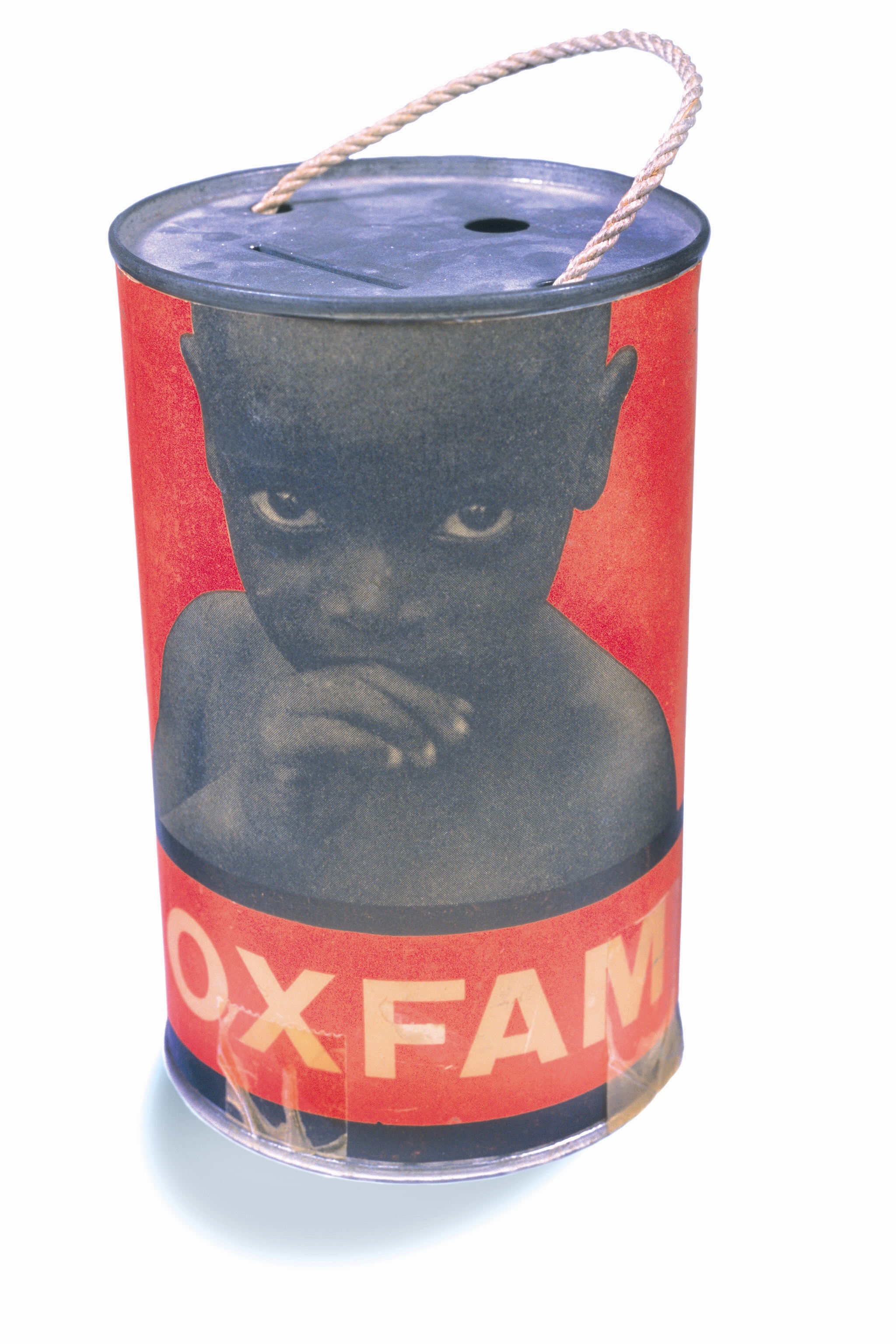

The second talk was about the Save the Children Fund archive and was given by Matthew Goodwin, Project Archivist at the Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham. The Save the Children Fund archive shares some immediate similarities with the Oxfam archive: it was acquired by the University of Birmingham at around the same time (2011) and is being catalogued thanks to a grant from the Wellcome Trust. The archive covers the activities of the charity in the 20th and early 21st Century and while it is smaller than the Oxfam archive, it still spans over 2000 boxes of material. Matthew noted some interesting trends that he came across in the archive, such as the charity’s move away from campaign material that included intense images of child poverty and towards more positive images that highlighted the charity’s life-saving work. This is a trend that is noticeable across the sector, as many humanitarian organisations have chosen to pivot their publicity materials in this way in recent years.

A particularly interesting discussion evolved around the challenges presented by archives that contain graphic or distressing material and how this effects the archivists cataloguing the collections and the readers who access them. Several attendees noted that their work with collections from humanitarian and aid organisations had presented this issue. Possible solutions discussed included inserting warning notices inside boxes containing especially graphic material to warn users in advance of their contents and seating those using these materials in separate parts of the reading room to prevent other readers from accidentally viewing them. The archival community has shown an increased awareness of these challenges in recent years and in 2017 the Archives and Records Association (ARA) released guidance for professionals working with potentially disturbing materials. Their documents explore the current research around ‘vicarious’ or secondary trauma and compassion fatigue, as well as offering practical techniques for staff and detailing how to access support. Their guidance can be found here: https://www.archives.org.uk/what-we-do/emotional-support-guides.html

Regrettably I wasn’t able to attend the afternoon workshop sessions which discussed the Red Cross Archive and Museum and how the collections of humanitarian organisations factor into the work of NGOs. Hopefully as my traineeship develops I will get a chance to revisit these collections and learn more!