As part of Oxford’s GLAM Digital Strategy, there has been some interesting research into audience archetypes. This work examines the many different aims people can have when engaging with our GLAM institutions: from “have fun” to “use collections in teaching”. The technology we use in GLAMs can help users in these goals, or can throw up frustrating barriers, and this strategic work explores how it could help.

Meanwhile, open platforms like Wikipedia continue to be the principal way in which people encounter cultural heritage. A growing “GLAM-Wiki” movement involves cultural institutions and volunteers in sharing collection data and building new tools, with some of those data sets coming from Oxford University. So is there an overlap between Oxford GLAMs’ aspirations and what Wikidata enables? In this post, I draw together some of my previous posts to show Wikidata’s role in advancing some aims mentioned in the document.

Find collections information without having to know how that data is organised using familiar/agreed terminology / Find content when I search for it via common search tools such as Google

One of Wikidata’s great strengths is as a multilingual store of names and identifiers for entities, linking through to further information. Consider the Iranian poet Ferdowsi, Wikidata has many dozens of renderings and transliterations of his name, across 94 languages. Hence people can find information about him in Wikidata-driven applications using the name they are familiar with, rather than having to guess whether the catalogue they are using calls him Ferdowsi, Firdausi, Firdousi….

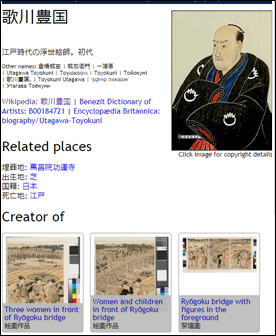

The Collection Explorer application combines some data sets from Oxford collections. It adjusts parts of its interface on the fly in response to the language of the user’s device. Here is how the user of a Japanese browser or device sees the profile of a Japanese artist:

Find links between objects across collections to enable presentation as “capsule collections” / Engage with people, places and things that are relevant to me to surface hidden collections online and to offer varied interpretations

As I’ve shown in previous posts, Wikidata is about connections between things, including between collection items and historical, mythological, and present-day entities. These connections are available to the user in various ways. In the Wikidata-viewer application Reasonator, the profile of an individual or place shows works connected to them. So for Arthur Evans, there are currently details for William Richmond’s portrait of him in the Ashmolean and for 32 of Evans’ drawings in the Pitt Rivers collection.

Some of the (many) properties of Arthur Evans visible in Reasonator

Collection Explorer makes explicit the connections between collection items, places, people and other entities. The Wikidata-driven visualisation of the Sibthorp-Bauer Expedition connects art works, species, places and times.

Easily find objects/books/specimens online rather than having to visit in person or contact GLAM staff

Wikidata has multiple ways to point to a digital record or digital surrogate:

- described at URL (which can point to an official collection record)

- full work at URL (which can point to a digitised version of the object)

- IIIF manifest which enables a document to be opened in an International Image Interoperability Format viewer.

- image where there is a freely shareable image on Wikimedia Commons.

Find secondary information related to collections such as articles, people or related objects

As well as expressing relations between collection items, Wikidata points to other kinds of data (some examples in this post) Most of the data in Wikidata are bibliographic and Scholia is a tool to browse those data by attributes such as topic, allowing for example a list of publications about astrolabes. Wikidata-driven applications can point to further information for people (e.g. VIAF), locations (e.g. GeoNames) and general topics (e.g. Britannica, Wikipedia, Getty Thesaurus).

Access detailed structured (machine readable) data across the collections

Data that have been shared on Wikidata can be queried, exported and visualised in a variety of formats. This online notebook gives a quick overview of what can be done with Jameel Centre data.

The data about an item in Wikidata are usually “tombstone” data, less detailed than the full collection record. Against that disadvantage, Wikidata offers other kinds of detail:

- links to sources of further data (e.g. IIIF manifests)

- data that are truly global, connecting items across many GLAM collections, (e.g. works of Utagawa Hiroshige)

- crowdsourced statements that go beyond the original collection record. This brings us to:

Support GLAM in creating and curating content

Wikidata and its sister projects are not just platforms for disseminating information but spaces in which the public can contribute suggestions to be incoporated back in the institution’s catalogues. An obvious area is depictions in representational art, where the catalogue usually lists the main subject that is depicted, but not all the depicted entities. Mobile games based on Wikidata can be used to elicit judgements which might be very generic (“Is this a portrait?”) or involve specialist knowledge. (“Is this Vajrasattva?”)

Andrew Lih’s recent blog post describes a project using automated classification and a Wikidata game to elicit thousands of depiction statements for paintings in The Met.

A concrete way in which Oxford GLAM collections have already benefited from sharing open data is in translations. As examples, three Bodleian Hebrew manuscripts (1, 2, 3) have had names and descriptions in Hebrew added by a Wikidata contributor. Three documents related to Georgia have had titles and descriptions translated into Georgian, Russian and Turkish (Click “All entered languages”: 1, 2, 3).

Post by Martin Poulter, Wikimedian In Residence

This post licensed under a CC-BY-SA 4.0 license