The professions associated with map making have historically been male dominated. In addition, women who were involved are not always recorded. The case of Sidney and Selina Hall, map engravers of London, is an instructive one.

Sidney Hall was born around 1788 and is recorded working as a map engraver from as early as 1809, based in Piccadilly and later in Bloomsbury. He was prolific and highly regarded and produced hundreds of finely engraved maps. He was probably the first map engraver to work on steel rather than copper plates; steel plates were harder to work, but enabled very fine engraving and were more durable.

In 1821 he married Selina Price of Radnorshire; there is uncertainty about the date of her birth but she appears to have been a few years his senior. We might have heard no more of Selina, were it not for the fact that Sidney Hall sadly died only 10 years later, at the age of 42. And yet his engraved maps continued to appear. New works engraved by Sidney Hall were published for decades after his death. Selina Hall, who conveniently shared a first initial with her husband, simply continued to engrave maps and signed them “S. Hall” (this as well as the date can be used to distinguish them from her husband’s work, since he usually signed “Sid.y Hall”), thus continuing to benefit from an established name.

In 1821 he married Selina Price of Radnorshire; there is uncertainty about the date of her birth but she appears to have been a few years his senior. We might have heard no more of Selina, were it not for the fact that Sidney Hall sadly died only 10 years later, at the age of 42. And yet his engraved maps continued to appear. New works engraved by Sidney Hall were published for decades after his death. Selina Hall, who conveniently shared a first initial with her husband, simply continued to engrave maps and signed them “S. Hall” (this as well as the date can be used to distinguish them from her husband’s work, since he usually signed “Sid.y Hall”), thus continuing to benefit from an established name.

Norfolk, from A new British atlas, 1836. C15 d.39

The first map shown here is from A new British atlas, first published in 1831 by Chapman and Hall. These were available bound in an atlas and as separately published items. The maps early on the alphabetical sequence are signed by Sidney Hall, and the later ones simply by S.Hall, suggesting that Sidney may have died in the middle of the project and his wife continued the work.

Engraving is a highly skilled job, and Selina Hall cannot have learnt it all at once on her husband’s death. It is far more likely that she was an active participant in the business throughout their marriage, but that her contribution was not ackowledged. She was certainly known to her husband’s former business partner, Michael Thomson, who died in 1816, since she is mentioned in his will, so she may have been involved in the map production process for even longer. Selina lived for over 20 years after her husband’s death, continuing to engrave maps, and when she died the business passed to her nephew Edward Weller; she may have been involved in his training.

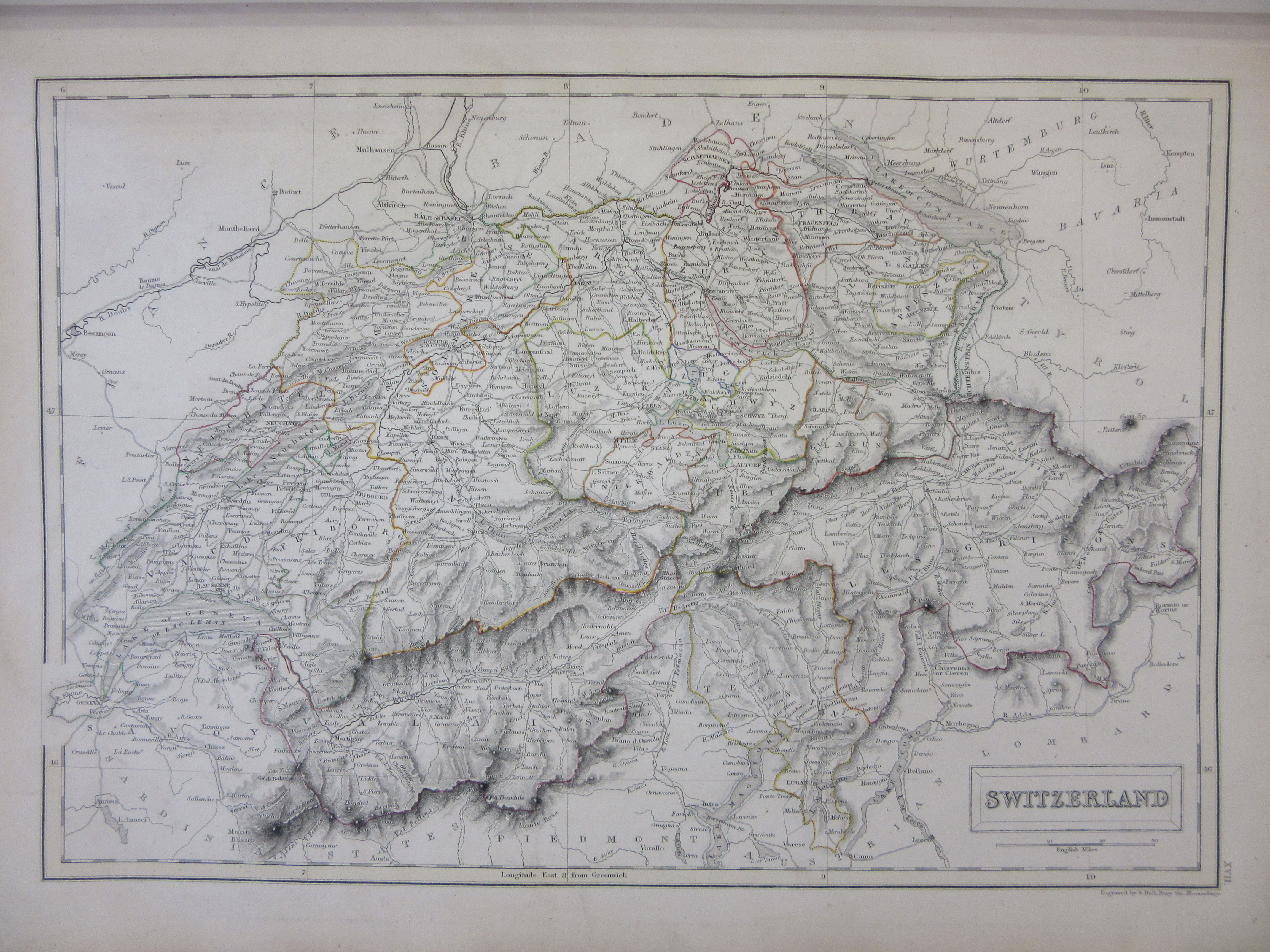

Switzerland. From Black’s general atlas, 1846. Allen LRO 80

Even works produced long after Sidney’s death continued to be attributed to him by researchers until recently, partly because his name was used to promote them at the time. The second map here is from Black’s general atlas of 1846 (first edition 1840); the title page boasts that the maps are “engraved on steel, in the first style of the art, by Sidney Hall, Hughes &c.” The signature S. Hall appears on this one.

Although Selina was an active and talented engraver, were it not for her husband’s untimely death we would have no evidence of her involvement at all. Which immediately raises the question: how many other female map makers, working in similar circumstances, are missing from the record?

Further info:

Worms, L., & Baynton-Williams, A.. British Map Engravers : A Dictionary of Engravers, Lithographers and Their Principal Employers to 1850. London: Rare Book Society, 2011.

Worms, L., ‘Hall, Sidney (1788/9?–1831)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/50861 (accessed 4 March 2020)

Pingback: Book Profile and Revue: 19th Century Newspaper Engravings of Ceylon – Sri Lanka by R.K. de Silva – collectingoldbooks.com

Pingback: Where are all the women? The case of the Halls – GeoNe.ws